February 27, 2024

Fresh Ink: When You Want to but Can’t

The English-language debut of Kyohei Sakaguchi’s self-help nonfiction writing

All of the articles in our Fresh Ink series highlight the English-language debuts of never-before translated works of prominent Japanese writers.

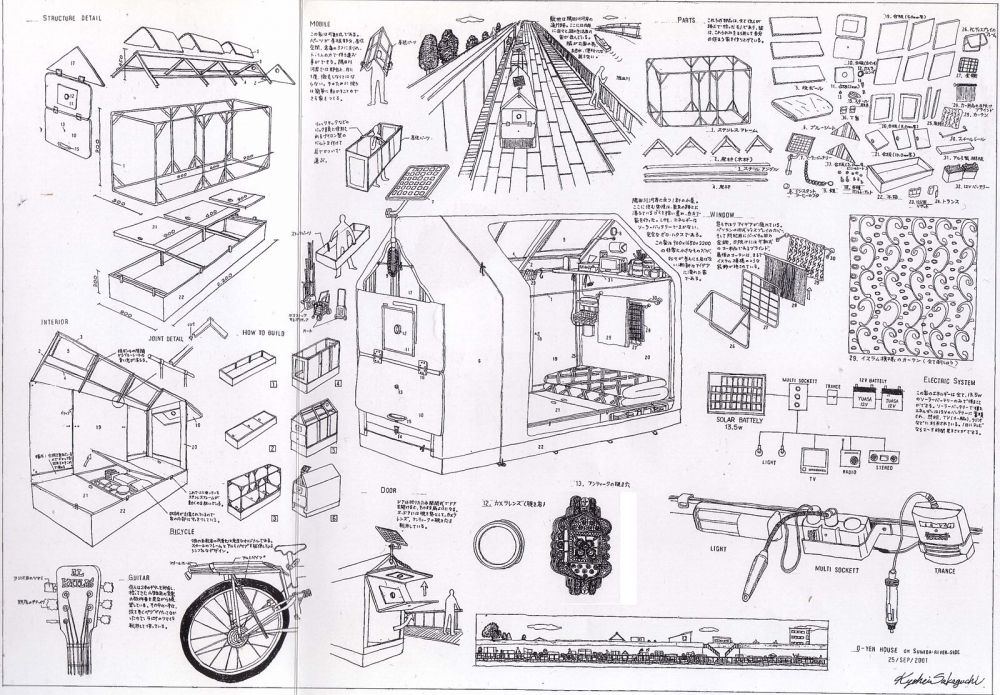

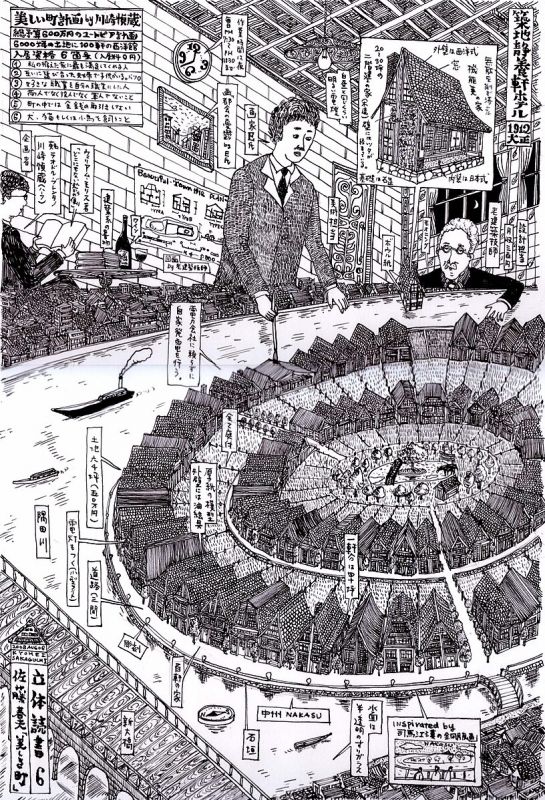

Kyohei Sakaguchi started off as an architect researching the “Zero-Yen” houses of Japan’s homeless population, impromptu dwellings of cardboard and reclaimed materials. But Sakaguchi grew to be much more—a versatile artist, experimental writer, musician, and self-help guru. Most notably, Sakaguchi independently operates a suicide hotline where he answers daily phone calls from people who want to die; in recent years, Sakaguchi painted a pastel every day for over a thousand days, and the results were recently exhibited at the Kumamoto Contemporary Art Museum. Embracing his own bipolar disorder, Sakaguchi is a unique contemporary Japanese icon of freedom and independence—a person whose life ambition and motto is to simply have a good time along the way. While his bizarre and twisty fiction is available in English in Monkey Magazine, this is the debut of his self-help-oriented nonfiction writing. The below is an edited excerpt from his 2022 book Renzoku Suru Kotsu (Tricks to keep doing things).

——-

Let me tell you a personal story.

I draw one picture every day. Every day, I give it a go. Why? Because it’s fun. And when I finish, there’s a brand new picture born into this world. As a father of two, I know very well just how astounding it is when something new is born into this world that didn’t used to be there—and how awesome it is.

Drawings aren’t much different, right? Something that didn’t previously exist gets born for the first time. That alone is plenty earth-shaking, but the more you draw, the more you get used to it. You get used to the surprise of it. You get used to how to draw something. Somewhere along the way, you get used to the shock of what it means to give birth to something new.

There’s no avoiding it. People get used to new things; we just do. So it’d be crazy to try to escape getting used to things altogether. Worrying about getting used to stuff is pretty much the same as worrying about eating or shitting—not only will doing so fail to solve the mystery, but the more you worry about it, the more you feel like some kind of alien. People even get used to sex of all things—sexless marriages have become a major social issue nowadays. But isn’t that also crazy—that the natural process of getting used to things can become a social issue? Something’s all wrong with the questions we’re asking here.

So: pictures. Every day, I draw one. But what happened when I got used to the surprise of seeing the birth of each new drawing?

Obviously, I didn’t stop—I started to want to make the quality of the drawings better. I started thinking that I had to make good drawings. I was supposed to be just drawing for the fun of the act itself, but instead, I was used to it. And when you’re used to things, you start forgetting the singular joy of the act you once so loved. I consider myself an expert on the art of keeping doing things, but I’m no different. All those feelings just disappear.

And when they did for me, a new feeling kicked in: the feeling that my drawings weren’t very good. The self-denial kicked in. Maybe not denial towards myself, but towards my drawings. It’s the same feeling as when, in a relationship, the husband latches on to the wife’s flaws, and the wife starts to notice all the stupid crap the husband pulls. It’s a natural development. Natural enough that it can legitimately become a major social issue—natural enough to be, well, a law of nature. And that point in time when you lose the freshness of doing something purely for the love of it comes a lot sooner than you’d think.

It’s not self-denial. It’s the denial of the other—the individuality of the other. I started to think my drawings were worthless because I was comparing them. Once I got used to drawing, I started to look around and realized that my drawings were nothing special at all. I started to compare—and I started the denial.

You begin thinking that you’ve got to produce a masterpiece. This happens even if you’re a beginner, the moment you get used to it. Now that you can do it, you’re thinking that you’re someone capable of producing a masterpiece. Sure, you might not want to say it out loud—but all of us fall prey to this thought. Which means that inevitably, inescapably, we start comparing ourselves to the people that we think are talented.

When I reached this stage, I didn’t feel down about myself, not yet. I forced myself to move my hands, to try to draw. But the denial revved up. Back when I was engrossed in drawing, I could spring my hands all over the campus, but now they had grown stiff. I didn’t want to fail. I wasn’t free. I started to think a truly useless thought: what would make for a good drawing? And since I still forced myself to make drawings in that state, my drawings weren’t free either. I could never be satisfied by those drawings. Now when I looked at them, I just felt depressed. And it’s not only me—this happens to a lot of people.

To be precise, we’ve totally lost all sense of joy. No fun at all. But this is getting the wrong idea of things. We’re not looking down at ourselves—we’re on our high horses. Sure, we’re both embarrassed to say it, but it’s because we want to draw something great ourselves. So now we don’t get better, we just feel bad for ourselves. Even though we didn’t do anything at all worth getting depressed over, that’s how we feel.

As a result, I lost all will to draw. I jumped straight to “I can’t produce a masterpiece, so my art is worthless.” I started seeing all the flaws of my own work.

If this feeling keeps going, you lose confidence and eventually the ability to make new art altogether.

A large number of the people who called me when they were contemplating suicide were in this exact situation. They were used to things, had lost all joy. They were denying the individuality of other people. They couldn’t stop comparing themselves to others. They were convinced that living had to be some great masterpiece and wanted to chase it, cornering themselves in the process. They looked at other art or other lives, and now the self-denial bullrushes them at top speed. The hand stops moving altogether. There’s no continuing this thing, not anymore.

In other words, the reason it’s so hard to keep going isn’t some ordinary gripe. There’s a law of nature behind it. And it’s unstoppable, undeniable.

So the question becomes, what can you do about it?

Personally, I have exactly two things that I do.

Number 1: Never do the exact same thing twice.

And number 2: Stop doing something the moment I don’t like it anymore.

That’s it. Neither of them seems to have anything to do with keeping doing things—in fact, they have to do with the very opposite. But the reason I’ve been able to keep doing everything I keep doing is because of these two tricks.

And before you run off thinking I’ve made a fool of you, just bear me out a little longer. Although to be honest, I don’t mind if you don’t actually listen. Because either way, I’ll say what I want to say. I’ll keep saying it. That’s why I can let it all go and still be assured that someday, somehow, it’ll find an ear. This isn’t just me giving up and screwing around, either—I’m doing these two tricks because they’ve proven effective for me, because they’ve allowed me to keep doing things.

I wrote this book in the same way. I wrote what I wanted to, when I wanted to, how I wanted to. I still wanted to keep writing it, of course, or I probably did, and I am, every day. I do what I do. Tomorrow, I don’t know if I’ll keep writing about these same topics or not. But that’s alright with me. Keeping doing things is about doing what you do, no more, no less—and when I wrote about these tricks for a magazine, before I knew they would turn into a book, the question of whether or not they would turn into a book didn’t matter to me at all.

When you simply do what you do, nothing is scary anymore. The whole point of life becomes to smile before you die. That’s all.

And since I’m getting bored of writing this right about now, I’ll wrap it up. In fact, this is page number 40 that I’ve written today. And that’s the key here: when you actually want to do something, you can do it like crazy. When you start thinking that you have to, you want to stop.

So people should think about what they want to do—for themselves, and for other people. If we actually do what we want, we’ll all become much kinder towards others. I’m sure of it.