May 31, 2023

Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s Kappa

Enter the absurdity of Kappa Land in this new English translation

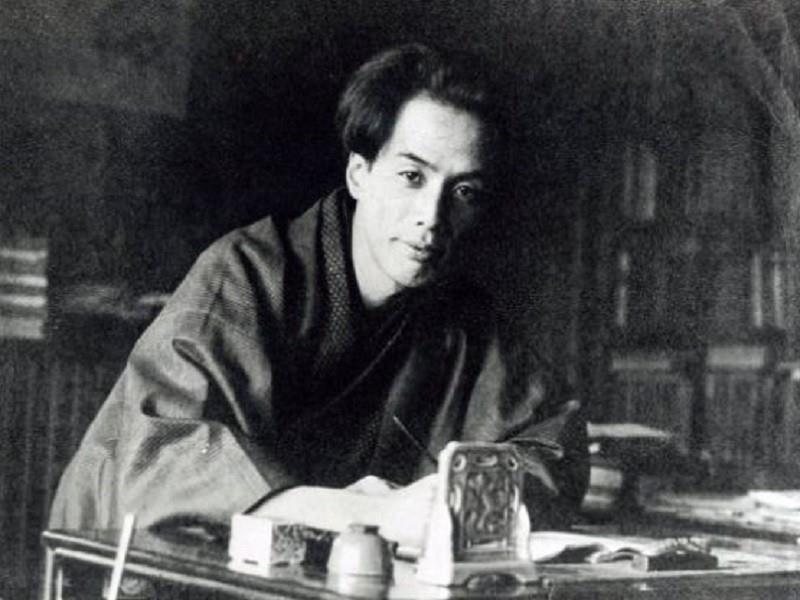

We have thousands of Facebook friends and Instagram followers, and yet we are isolated from our neighbors. New technologies that were supposed to make our lives easier have often trapped us at our jobs, devastated our careers, and ruined our mental health. We live, as the great novelist Ryunosuke Akutagawa did, in an era of absurdity.

In his final and hotly debated 1927 work Kappa, Akutagawa keenly discerns the ironies of his own era. The Taisho period in Japan was defined by flourishing culture as military factions began to exert control over politics and society. Akutagawa observes economic productivity and rapid growth in the face of brutal social inequality; the intake of Western values and the resulting backlash towards nationalism and tradition. All of the insanity and madness that belonged to this era of supposed artistic and intellectual progress.

But Kappa is far from a simple parody. The protagonist and narrator’s diagnosed schizophrenia undercuts and simultaneously emphasizes every seeming argument Akutagawa seems to make about 1920s Japanese society. It is a fitting novel for our own discourse era, where an overload of information is regularly taken out of context, easily manipulated for sinister purposes, and boosted with likes and shares.

On June 6 from New Directions, Kappa will receive fresh life in English. This will be its first translation in over fifty years, by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda and Allison Markin Powell.

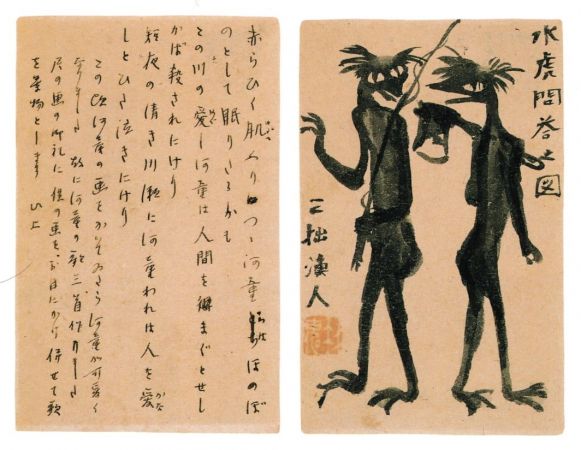

Kappa is a fusion of Gulliver’s Travels and Alice in Wonderland with Japanese mythology. It tells the story of an unnamed psychiatric patient who wandered into Kappa Land, the home of the scaly yokai said to be found in ponds and rivers, capable of minor mischief and malevolent violence.

But Patient No. 23 discovers that kappa live in a world eerily similar to and yet strangely different from Japanese society. Kappa Land is a highly developed nation with large-scale manufacturing, wars, and a flourishing artistic and literary scene.

Everything about Kappa Land is equal parts familiar and ridiculous. Kappa love involves a female relentlessly, single-mindedly chasing a male until she snatches him, causing the male endless torment. Kappa concerts, technically prohibited by the government, are complete mayhem, with chairs, bottles, programs and half-eaten cucumbers getting chucked at the performer and all over the place. Everything about Kappa Land is also highly dystopian, as misery, industrial-scale murder, tyranny and suicide populate the book’s pages.

Each absurdity is twice as dark as it is humorous. And yet Kappa Land’s parallels to Japan are almost too on the nose. Akutagawa portrays kappa like a strange society of humans, with their own prejudices, practices and ironies. It stands to reason that Kappa may be a straightforward critique of Japanese society, and some critics at the time viewed the work as no more than a crass, unpolished parody.

“Most of the scholarship on Kappa tends to fall along one side of a pretty simplistic binary (was it a critique of Taisho society or a reflection of Akutagawa’s personal madness), and it is probably some of both,” Hofmann-Kuroda writes over email. “But part of me also feels that Akutagawa was observant and something of a visionary… And indeed, the 1930s would see Japan embrace fascism, militarism, political torture and censorship of artists and intellectuals to the fullest extent.”

Meanwhile, Akutagawa’s biting critique of capitalism in the work, where “black box” machines pump out finished products and workers are killed when they are laid off, is just as relevant today. “I can’t help but think of the strikes at Amazon, Starbucks and various universities… and the ongoing brutal suppression of workers whose labor is constantly being made redundant by technological progress,” says Hofmann-Kuroda.

In 1927, Akutagawa committed suicide—the same year Kappa was released. The fable represents the significant shift in his writing towards the end of his life. Akutagawa’s early career was defined by his retellings of ancient Japanese tales with an eye towards modern psychology and modernist literary styles. But in the 1920s, as his mental health declined and he suffered from hallucinations and nervousness, he shifted towards autobiographical fiction.

So within his canon, Kappa stands out. It is far and away the least realist of Akutagawa’s works, and as Hofmann-Kuroda observes, his only book with non-human characters. At the same time, many of the qualities that led Akutagawa to his status as one of Japan’s greatest authors are present in Kappa: his inventive molding of mythology, his experimentation with a point of view that undermines the reliability of the narrative, his use of irony and aphorism (in fact, one chapter of the book consists entirely of kappa sayings).

Nowhere can Akutagawa’s intentional undermining be more clearly seen than in the poet kappa named Tok. Critics agree that Tok is a self-parody: a cynical, grandiose, polyamorous writer obsessed with his own reputation. Even readers at the time would have been aware that Tok represented Akutagawa, which adds a whole new layer of bleak irony to the work, written as it was in the throes of Akutagawa’s depression.

“It was so striking to me how even in the midst of raging psychosis and despair, Akutagawa was lucid and self-aware enough to have this ironic distance from his own misery, to make light of and ridicule himself to the point of cartoonish parody,” says Hofmann-Kuroda.

Although less funny than disturbing, and lacking much of a narrative drive, at a concise 82 pages, Kappa is an essential read for the current moment. Akutagawa illustrates absurdity in his own era in the messiest possible way, and if there’s anything we can take away from this book, it is at the very least the impetus to see our own age with a clearer set of eyes.

The new translation aims to bring the book back into the conversation and update the language for a contemporary readership. It succeeds in doing so, retaining the intellectual feel of the Taisho era, even as Akutagawa’s brutal irony drips from every word.

For those in search of more Akutagawa, a collection of yet-untranslated “very short” stories will be released later this year by Paper + Ink, In Dreams: The Very Short Stories of Ryunosuke Akutagawa, translated by Ryan Choi.