December 4, 2019

Who Will Save the 2,000 Yen Bill?

The future of Japan’s most inconvenient note

There are few easier ways to contort a local Japanese business owner’s face than handing them a nice, crisp ¥2,000 note.

Many foreigners choose to exchange their cash for yen before even getting to the airport, preferring to do the transaction as cheaply as possible by going to their local bank. Domestic institutions, after all, usually offer the most favorable rates and can take care of the exchange quickly. However, a foreigner visiting Japan for the first time may be surprised to see the reactions their Japanese notes will cause when they hail their first taxi or fork over cash for their first lunch. With a furrowed brow and cocked head, the employee holds the bank note as gently as possible and asks, “Are… you sure you want to pay with this?”

The ¥2,000 notes are legal tender and on equal footing with any other bill in Japan, from ¥1,000 to ¥10,000. In Japan, however, they’re all but extinct. The ¥2,000 note is notable for being the only currently issued bill that doesn’t have a portrait on its face side. Instead, the front of the note has a detailed rendering of the Shurei-mon — a 16th century gate outside of Shuri Castle. It’s a famous cultural landmark of Okinawa.

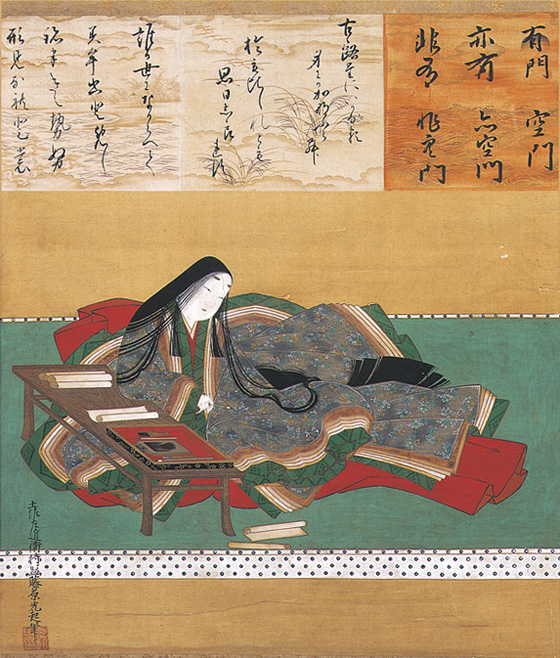

The reverse of the bill depicts an ukiyo-e (woodblock print) of the main character in “The Tale of Genji,” a Heian period story considered by scholars to be the first novel ever written. Text from the 38th chapter, in which Genji visits a former lover who has become a nun and thus comes face-to-face with his fickle desires, is written vertically in calligraphy over the scene.

In the bottom corner of the green note is a circular portrait of the author of “The Tale of Genji,” Murasaki Shikibu. She is smiling in period-appropriate dress and make-up, her face only slightly obscured by a screen.

Sometimes, the surprise at a ¥2,000 bill is out of genuine concern — these green notes are rare, after all. Surely you don’t want to toss away such a rare bill on a bowl of ramen in a random Tokyo neighborhood?

Other times, it can come across as a polite request to get something a little more manageable. Modern Japanese cash registers sometimes don’t have a drawer or slot for the ¥2,000 notes, leading many cashiers or business owners to begrudgingly shove the green paper into a wrong slot or under the register.

It’s a beautiful note. So why don’t we ever get to see it? Ai Nicholls is the owner and bartender of The Alchemist, an upscale steak and hamburger restaurant in Niigata Prefecture. Despite running her business in Japan for more than two years, Ai has only seen the ¥2,000 note once in her life. But she’s been told that they can be tricky. “I heard that [other business owners] don’t like using them [because] when they are in a hurry, they look like ¥5,000 or ¥10,000 notes.” She’s never received one as payment for a meal, and even if she had, her cash register doesn’t even have a spot for them.

“Our shop will, of course, accept ¥2,000 bills,” says Shintaro Kaneko, owner of a small soba restaurant called Gojou. “I go to the bank regularly, so as long as I can still use ¥2,000 bills there I don’t see any problem with them.”

“People living in the city are probably used to foreign customers paying with ¥2,000 bills, but there might be a lot of people living in rural areas who are not as accustomed to it,” says Kaneko. “That could be why it feels different in certain places.”

The most authoritative voice on the issue of bank note circulation in Japan are the people who make the bills and throw them into the national and world economies — the Ministry of Finance. When asked about the possibility of the ¥2,000 note receiving a surprise comeback through the unknowing influence of the incoming foreign hordes, the ministry was less than concerned.

“We do not necessarily expect to see a huge influx of ¥2,000 notes,” said Takaku Imamura, an administrative counselor at the Ministry of Finance. “While more and more foreigners (approximately 31 million in 2018) are visiting Japan recently, a serious influx of ¥2,000 [notes] has not occurred.”

It’s nearly impossible to calculate the total number of visitors who will arrive for the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Beyond ticket holders and athletes, a variety of collateral visitors must be accounted for: families, foreign staff members, translators, business partners, and most importantly, Olympic and non-Olympic tourists inspired by the worldwide attention.

How many of these people will go to the bank beforehand and come to Japan with a pocketful of ¥2,000 bills? It’s hard to say. But in Tokyo, a city with a greater metropolitan population of over 38,000,000, perhaps the Ministry of Finance is justified in its lack of concern for a legal tender revolution. But what about the mom and pop shops that will probably have the bills put in their hands at some point or another?

For small businesses accepting the weird foreign-but-not-really-foreign currency, the Ministry of Finance claimed no authority or additional insight, but did place themselves firmly in the pro-2,000 camp.

“The Ministry of Finance has been promoting the use of [¥2,000 notes] in light of convenient settlement considering the relatively high demand for banknotes beginning with a “2” in foreign economies,” said Imamura. “[The] ¥2,000 notes would be produced as necessary should there be a larger demand.”

“We have been promoting a wider use of ¥2,000 banknotes, though our ministry can neither make any comment on nor expect whether small businesses accept the bills.”

So, how can we save this beautifully designed and culturally significant note?

The vast majority of these greenbacks are held in overseas banks and used in international deals outside of Japan’s borders. They were created specifically in order to make cash transactions easier for foreign banks and governments, and their use by the Japanese public was secondary to that goal.

Yet, if the Ministry of Finance is correct, the influx of foreigners is expected to make no noticeable change in the availability of the ¥2,000 bills. They’re not going to be bringing enough of them to get the ¥2,000 bill system pumping domestically.

The Ministry of Finance says that they’d like to increase their use, and are willing to print more if the demand exists, but so far they haven’t done much.

Perhaps then, the ¥2,000 note is destined to be an outward-looking, international ambassador of Japanese currency.

The little green slip of paper is a wandering native of Japan — thoroughly Japanese in its appearance and culture, but resigned to a life abroad with only the occasional return back home.