August 6, 2019

The Sempo Museum

A curated, narrative exhibition of Japan’s Righteous Among the Nations

Chiune Sugihara, the so-called Schindler of Japan, has inspired a museum in Tokyo dedicated to the selfless aid he rendered to thousands of persecuted Jews in 1940. While just a humble, one-room showcase of his life, it has already attracted guests from around the world, flocking to see the personal memoirs and photographs of Japan’s only Righteous Among the Nations (non-Jews who took great risks to save Jews during the Holocaust).

“The survival of both my parents, and therefore my very existence, is a result of [Sugihara’s] profoundly humane actions under very difficult circumstances. For me this is a very emotional matter that resonates deep in my heart and my consciousness.”

This is a quote from a visitor that Gary Perlman, advisor to the Sempo Museum, offers as a testament to the impact that one Japanese man made on the world over the course of just one month while stationed overseas. “Sempo” was the pseudonym of Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese Imperial Vice Consul to Lithuania during the years of World War II.

In 1940, with the Soviet annexation of the Baltic States, Polish and Lithuanian Jews began to seek ways out of their countries and move into safer, less volatile homes without fear of persecution or political violence. Inundated with requests for visas from terrified and desperate Jews, Sugihara contacted his superiors in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs repeatedly, but was left with either non-committal deferments to other officials, or instructions not to issue such papers.

This is the situation that Chiune Sugihara found himself in — stranded in a foreign land with help available to those suffering around him — but strict orders not to provide it. And it is this story that the Sempo Museum seeks to walk its visitors through — action after terrifying action in the face of the Imperial Government.

Sempo — the namesake of the museum — is what Sugihara asked the refugees to call him throughout their communications. It is the Chinese reading of his proper given name, Chiune, a name that many of the European Jews were unable to properly pronounce.

Located just a few minutes brisk walk from Tokyo Station, the Sempo Museum is not an ornate or flamboyant affair. The medium-sized room is tucked up a flight of stairs above a bustling restaurant on the opposite side of the station from the Imperial Palace. Advertisement for the small gallery on the street is minimal, and one can be forgiven for walking past it once or twice while seeking it out. But what’s inside is perhaps the most powerful museum of its kind in Japan. And the story that it tells is unlike any other.

With the Baltic conflict boiling over and Sugihara’s own ordered withdrawal from the country a likelihood, the window of opportunity for him to help those petitioning his consulate continued to shrink.

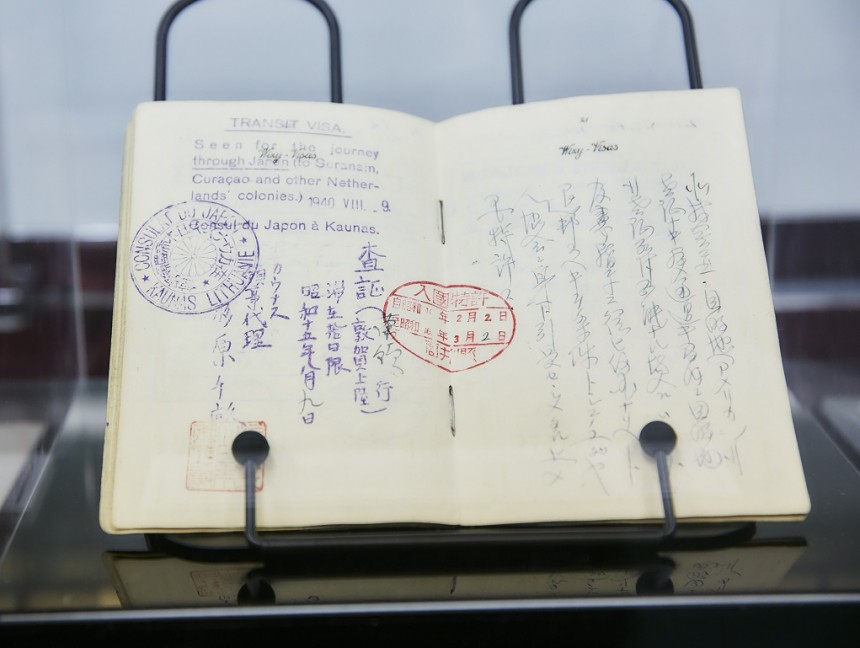

After much prayer and contemplation, Sugihara made his solemn decision. Over the course of more than a month, he wrote enough visas to save over 6,000 refugees — all by hand and with the assistance of his wife, Yukiko. They wrote the documents for more than 18 hours a day, cramping their hands and foregoing sleep, writing an unprecedented amount of documents with little care about the ministry’s inevitable protests.

This was in direct disobedience to his superiors, and could have led to cruel and violent punishment for himself and his whole family. But Sugihara continued to scribble madly at visas all the way until his forced departure from Lithuania in August of 1940.

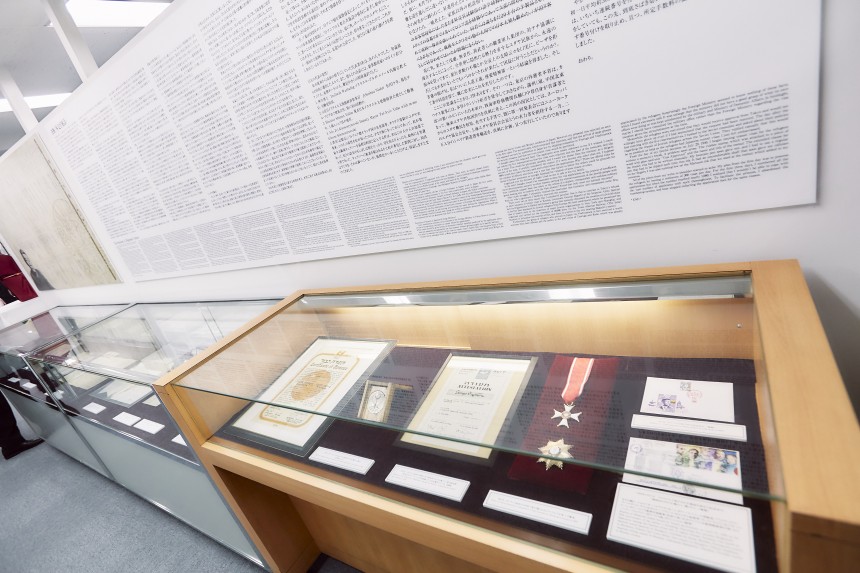

At the Sempo Museum, emphasis is placed on curating and displaying the story of Sugihara through pictures, text and video, as opposed to simply sticking his old belongings behind glass. Guests will find unpublished notes and entries written by Sugihara himself, reflecting on the situation in a previously unseen and tumultuous internal conflict. Additionally, private photographs of the man and his family, as well as the consulate in which they lived, have been pulled from his personal collection.

“The response has been extremely positive, especially for the comprehensive way the story is told through the panels and photos,” Perlman said in an interview. “The video documentary, handwritten memoirs and Wall of Survivors have attracted the most comments.”

The interior of the exhibition is straight-forward. There are minimal stylistic decisions on décor: white walls, white shades on the windows, and a soft gray carpet that one scarcely notices. Set pieces only include period-replicas of various travel and governmental documents to set the mood: fountain pens, bundles of cumbersome mid-1900’s luggage and visa stamps.

One would think it’s a purposeful decision — if anything should be presented as respectfully as possible without stylistic flourishes, it’s a Holocaust museum. A wall near the entrance displays all recorded names of those who received his handwritten visas, ordered alphabetically and stretching for several yards. Photographs of survivors are also on display.

The museum estimates that approximately 15 percent of its traffic is foreign. Sometimes, descendants of the original Jewish survivors find their way to the exhibit and are overcome with emotion. “One was left in tears; two brothers, the sons of survivors, spotted their parents in one of the photos,” Perlman said.

A corner of the museum space is devoted to a musical written about Sugihara’s story — written, recorded and performed in Japan, with clips available for viewing. The Sempo Museum has its sights on a few more pieces to display, namely journals which have been locked away for decades: “There is particular demand for the memoirs, which tell the story in Sugihara’s own words. They have been stored in a safe since they were written and have never been published in any form.”

With eyes on expansions and new offerings, the Sempo Museum is worth astronomically more than its meager price of admission. In a country ravaged and scorned by its history in the most massive and bloody war of the modern era, the Sempo Museum offers a rare and welcomed memory of gratitude and admiration in such a ruthless time.

Even more than that, it inspires in its visitors a deep sense of perspective, and a yearning to be as resilient in the face of whatever evils they may one day confront.