The northern parts of Honshu, Hokkaido, and its surrounding islands did not originally belong to Japan. The area was the home of aboriginal people, the Ainu. However, due to the Japanese government’s aim to expand their power and influence, the Ainu gradually saw themselves deprived of their land, language and customs.

Japanese settler colonialism of the Ainu land emerged in 1868. However historical studies clearly show that the commercial- and exploitation colonialism of the Ainu begun many centuries before that.

While deep scars of historical economic, social and physical suffering remains, the Ainu continue to face oppression in Japanese society. Because although the occupation of the Ainu and their land is said to have ended in 1997, the Ainu is still far from being a decolonized people. Due to the evident remains of Japan’s colonial legacy the discriminative treatment of the Ainu did never stop but stand as a current issue.

As a reaction to this, the 21st century has seen an increasing number of movements, born out of a desire to reclaim the Ainu peoples’ space in society. Through insistence for policy amendments, and art exchange with other aboriginal peoples around the world, Ainu and their allies continue to call for recognition and justice from the Japanese government.

The beginning of the Japanese colonial legacy

Historically based in the northern parts of Honshu, Hokkaido, the Kuril and Sakhalin Islands, the Ainu spoke their own distinct languages and dialects. The Foundation for Ainu Culture has published educational textbooks in eight Ainu dialects. These dialects, which may as well be referred to as languages, make up the Ainu language family. It is considered a language family isolate meaning it has no connections or roots with other languages known today. As hunters and gatherers, the Ainu valued nature highly, something that was, and still is, often expressed in their art.

Although some argue that the historical trade between Ainu and Japanese (taking form in the 1400s) contributed to peaceful, cultural exchange, one must not overlook the severe harassment and misuse of power that Japan acted upon the Ainu. Policies on family separation, forced marriage to Japanese citizens, slavery and obligatory assimilation to become “Japanese” continued throughout centuries. Resistance from the Ainu resulted in repeated wars with Japan. The Koshamain’s War (1475), Shakushain’s revolt (1669-1672) and the Menashi–Kunashir rebellion (1789) are a few examples.

Ainu in today’s Japan

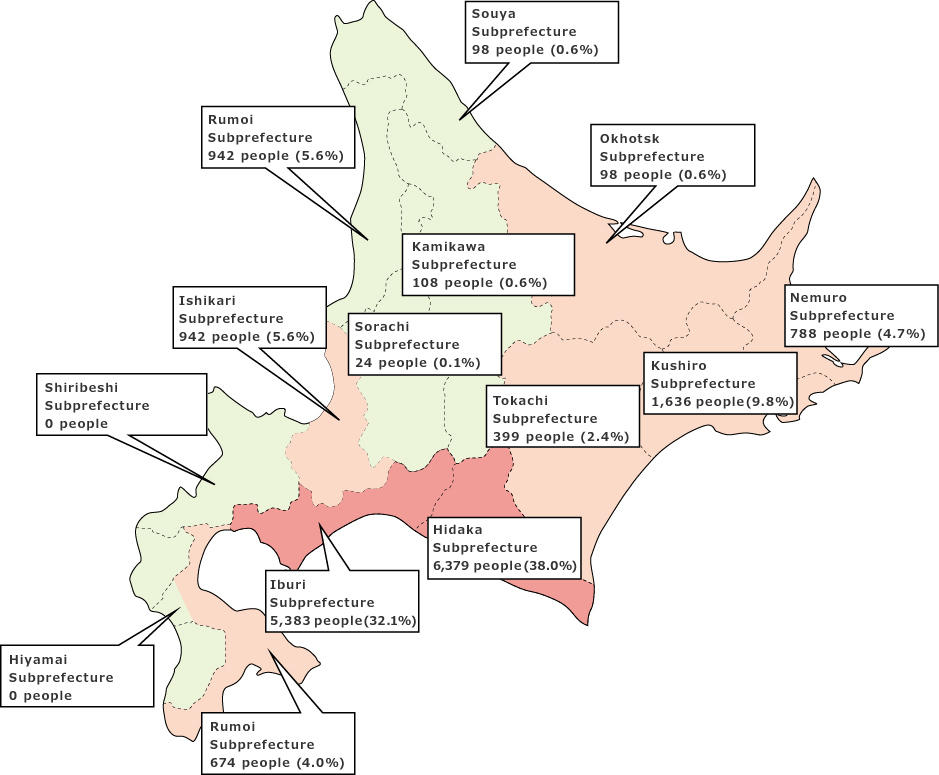

Now, Ainu are considered to be Japanese citizens and, according to Hiroshi Maruyama, director of the Centre for Environmental and Minority Policy Studies (CEMiPoS), it’s estimated that there are about 20,000 people in Hokkaido who identify themselves as Ainu today.

However, despite the Ainu’s long history and complex ties to Japan, few Japanese people — especially outside of Hokkaido — can confidently say they know much about their former neighbors, turned fellow citizens, of the north. One possible reason for this is that there are little to no encounters or interaction with Ainu people and culture on an every-day basis.

As times have changed, an increasing number of museums and galleries host exhibitions about Ainu art and tradition, allowing the general public to experience the beauty of traditional Ainu art and craftsmanship. Unfortunately, since these exhibitions predominantly focus on the history of the Ainu, both Japanese and international scholars argue that Ainu culture is falsely presented as belonging to the past. This lack of modern representation, in the worst case scenarios, leads to the vast misinterpretation that “the Ainu do not exist anymore.”

Thankfully, some silver linings of change seem to be peeking through the clouds of misfortune. Indigenous Ainu YouTuber Maya Sekine and manga writer Satoru Noda, with the help of Ainu language linguist Hiroshi Nakagawa, are taking the matter into their own hands, using their talents to increase interest in and awareness of the Ainu language and culture among Japanese citizens.

According to Shohei Uda, Hokkaido-born photographer from Asahikawa, the presence of Ainu people has always been something he was aware of.

“Almost every road sign features places and rivers written in both Japanese and the Ainu language,” says Uda. “This has made me conscious about the geographic history of Hokkaido. I remember going with my class in elementary school to a museum related to Ainu culture. But like most kids I didn’t enjoy museums in general at the time and don’t remember anything particular from that school trip.”

Although Uda’s memories from his elementary school Ainu teachings are not very vivid, he mentions that his interest for the indigenous people of his home prefecture has increased considerably in recent years.

“I went to the Kawamura Kaneto Anyu Museum. From an adult’s perspective one sees things differently,” he says. “It would be great if there were more opportunities for adults [throughout Japan] to study about Ainu culture.”

Established in 1916, the Kawamura Kaneto Aynu Museum is the oldest of its kind. Containing over 500 items of Ainu lifestyle and clothing, the museum is a special place for the Ainu community and often features live performances of Ainu dances.

It would be great if there were more opportunities for adults to study about Ainu culture.

The decolonization and controversy of Upopoy

Upopoy is an establishment for research and promotion of Ainu culture that opened to the public in 2020. Located in Shiraoi, Hokkaido, the facility and its exhibitions were created as a result of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Its mission was to oversee that the Japanese government followed the principles and policies set out in the declaration.

Although Upopoy was sought to be a unifying instance for the Ainu, it turned out to exclude majority of the people it was created to represent as only one of the many Ainu organizations in Japan — the Ainu Association of Hokkaido (AAH) — was asked to take part in the project and resulting conversations with the Japanese government regarding policies.

“The exclusion of these organizations is inconsistent with international human rights standards ensuring Indigenous peoples’ right to grant their free, prior and informed consent to decisions affecting them through their own representative institutions,” says Maruyama. “Given the fact that every working group, council and institution formed by the Japanese government in relation to the Ainu has been chaired by ethnic Japanese, including Upopoy, even the AAH can hardly influence decisions affecting the Ainu. In this context, Japan’s Ainu policy is far from decolonization.”

Japan’s Ainu policy is far from decolonization.

Disputes over stolen ancestral remains

Another issue that Ainu people are currently facing is the repatriation of ancestral remains. During the 1800s, Ainu graves were exhumed and remains were stolen for the purpose of research. Although some — albeit without proper apology — have been returned to the Ainu people by the museums, universities and institutes where they were once stored, many of the stolen remains have yet to be returned to the families.

“The repatriation and reburial of those human remains could / should be a good opportunity to reconcile the conflict between the Ainu, the twelve universities and the Japanese government over the unethical research and management of Ainu human remains,” Maruyama says.

Future prospects

The experience of colonial rule, the legal ban on language, traditional dress, spiritual beliefs and customs is something that the Ainu people share with many other aboriginal peoples around the world. As a minority in one’s own land, a community created through international organizations and associations can be helpful.

By sharing difficult experiences and progress related to decolonization, indigenous groups can inspire and learn from each other. At the present, Maruyama is working on a campaign for the amendment of the Ainu Policy Promotion Act of 2019 in accordance with international human rights standards. With the use of a questionnaire he plans to make Ainu voices heard and the present Act can be reviewed and amended in 2024.

The Ainu have long faced severe discrimination and exclusion as colonial subjects to Japan. However, despite the general perception that the colonial rule is now over, the present situation tells the opposite. The exclusion from policy making, the lack of representation and the dismissal of the issue of not yet repatriated remains, the Ainu do not have peace. As long as the Japanese government continues to show no genuine interest to make amends, a reconciliation will be difficult. No colonial damage nor harm can be undone, but to dismiss the Ainu people’s wounds may make them even deeper.