May 15, 2019

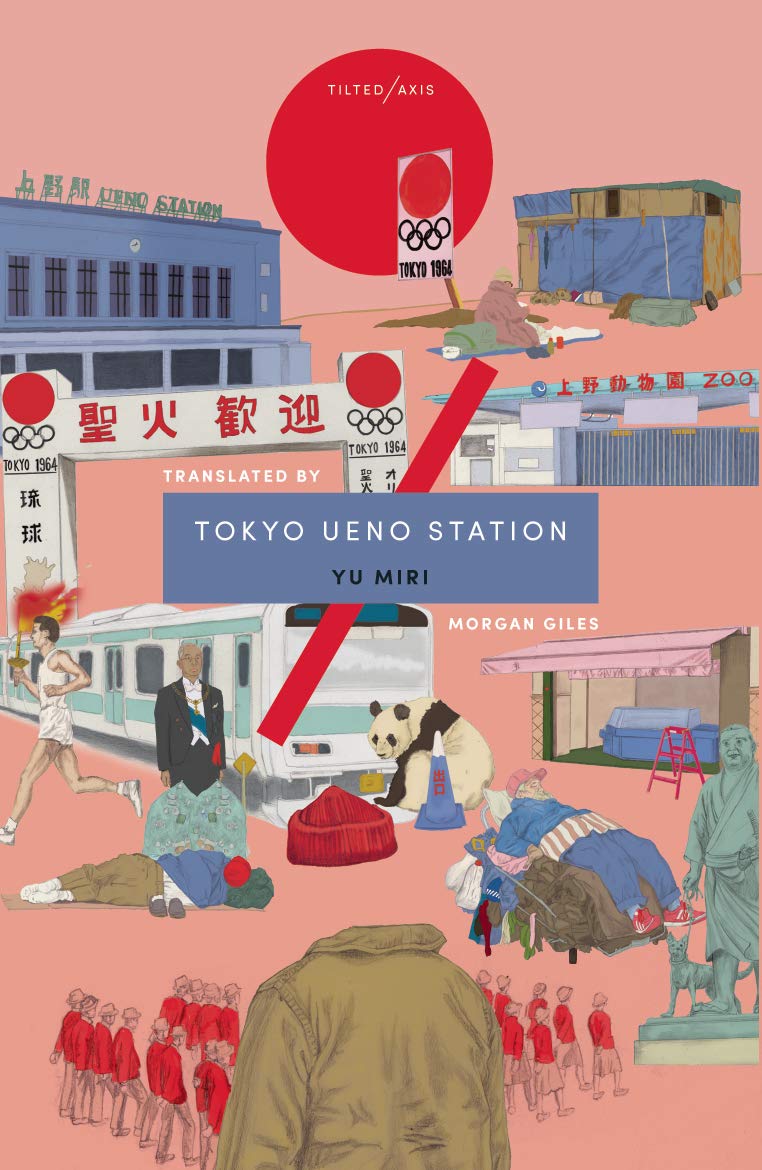

Tokyo Ueno Station

Yu Miri’s latest novel offers an intimate insight into a harsher side of Tokyo

Recently translated into English by Morgan Giles through Tilted Axis Press, Yu Miri’s latest novel, “Tokyo Ueno Station” offers an intimate insight into a harsher side of Tokyo that we often do not — or choose not — to notice. Whereas crowds exiting the gates at Ueno Station are often drawn to Ueno Park, the zoo and cultural museums, Miri forces us to refocus our attention instead onto the homeless community living in the park grounds, and invites us to hear the haunting experiences that led them there.

In particular, we see the world through the eyes of Kazu, a man who once lived in the park and now watches from the afterlife. Like many homeless people, Kazu once had a life with a home, family and work. However, once homeless, we see him transformed into a living ghost by a society that often dismisses and overlooks the reality of homelessness in Tokyo. The authorities force eviction out of the park when the Imperial family visit the area and brush the homeless village out of public sight whenever they deem necessary.

To be homeless is to be ignored when people walk past, while still being in full view of everyone. p.137

“Tokyo Ueno Station” challenges readers to break this social distance. It invites us to sit inside the park inhabitants’ tarpaulin and cardboard huts and hear these silenced voices tell their own histories. Although the public appear largely unaware of the homeless in the area, the snippets of conversation we catch from passersby revealing their absorption in their own lives, the novel pushes readers to see the inhabitants as any other human being, as individuals with struggles, successes and pasts.

Miri also invites us to take a step back and look at the bigger-picture, gradually revealing an overview of the major historical events that happened in Japan over the course of Kazu’s life, and how these contributed to the overall issue of homelessness in the country today. From the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, where Kazu worked as a laborer building stadiums, to the asset bubble crash in 1992 and the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011, we see Kazu’s fate unfurl.

However, this psychogeographical novel refuses to present these events chronologically or in perfect clarity. Instead it favors a more fragmented narrative similar to that of John Dos Passos’s “Manhattan Transfer,” or the non-linear style of writers like Kurt Vonnegut in his seminal “Slaughterhouse-Five.” The drive to want to piece these links together keeps the reader hooked and the park acts as an important constant in this challenge. Like layers in sedimentary rock, Kazu’s personal memories and the country’s history overlap and build on top of the park, shaping what it is today. Even in death, Kazu cannot escape this weight and is left to make sense of these fragments that defined him.

All these elements make “Tokyo Ueno Station” an insightful, short novel that sensitively observes the social issues it concerns itself with, instead of pushing towards a more opinionated critique. As Japan gears itself up to take center stage once again for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, the issues raised couldn’t have been published at a more apt time. How will Japan handle the human workforce this time round, and what image of Japanese society will the global audience see and, ultimately, celebrate?

Elsewhere on Metropolis: