July 3, 2020

Breasts, Eggs and Existential Feminism

Mieko Kawakami’s intimate portrait of womanhood in 'Breasts and Eggs'

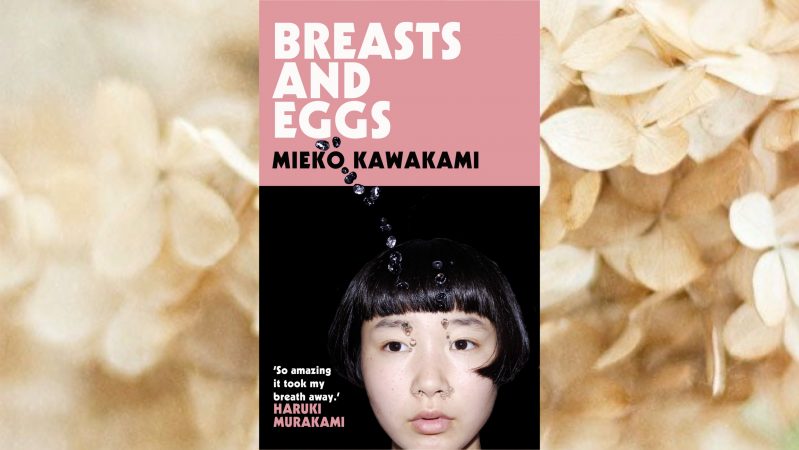

Within just a few years of beginning to write, Mieko Kawakami went from J-pop artist and feminist blogger to sweeping the entire Japanese literary awards cycle: the Tsubouchi Shoyo Prize for Emerging Young Writers, the Murasaki Shikibu Prize for Literature, Granta Best of Young Japanese Novelists, and most impressively, the Akutagawa Prize, the most respected literary prize in Japan. It is the story that won her the big fish —”Breasts and Eggs”— that, after more than a decade, finally came out this year in English translation as a reworked and expanded version of the original novella.

At the heart of “Breasts and Eggs” is a debate around the value of life itself and whether it’s selfish or unselfish to bring new life into the world.

Natsuko, a novelist in her late 30s, spends the second half of the novel debating with herself and the world around her on whether or not to have a baby. Poverty, a fractured family, misogyny, social pressure and all of the biggest and most minute moments of her own life show her that it is an awful idea to bring new life into an awful world.

This perspective is verbalized by Yuriko, who is the child of an artificial insemination. Having a child is an act of violence, she tells Natsuko. “People always feel sorry for me. Poor you, never knowing your real parents, living through years of abuse…. [But] I don’t need anyone’s pity. Whatever it is I’ve had to live through, it’s nothing compared to being born.”

View this post on Instagram

Her perspective resonates with Natsuko, who knows firsthand the trauma and pain of simply being alive. Kawakami depicts it on each and every page, diving deep into Natsuko’s consciousness and unearthing every anxiety, every memory for a reader to see and feel.

Kawakami’s depiction of Natsuko’s reaction to Yuriko’s declaration demonstrates Kawakami’s outstanding prose (as well as the skill of the translation by Sam Bett and David Boyd): “I was left with a weird sense of desolation, like a girl left standing on a corner in an empty, unfamiliar town. The orange sun would sink into the murk, while the telescoping shadows sidled up to her, as if they had something to say. Overcome with unspeakable terror, I could see the dark eaves of the houses, and the dull gray of the fences, and the cool refusal of the windows. Had I stood on that corner myself? Or was this just my imagination? At that point, it was hard to say.”

“I try to capture the light, the scenery of a single moment into my writing,” Kawakami tells Metropolis in a recent interview. “Fiction doesn’t have to be realistic, but it still has the power to point out new possibilities for our lives.”

I would love for my international readers to start thinking about the lives of people that they don’t know, and even turn to face themselves and their own lives.

— Mieko Kawakami

The novel begins when Natsuko’s sister, Makiko, and her daughter Midoriko, visit Natsuko in Tokyo. Makiko, who works in Osaka’s nightlife industry as a hostess, decides to get breast enhancement surgery, to the pubescent Midoriko’s distress. The novel resumes years after the encounter once Natsuko establishes herself as a novelist and can’t help but to want to have a child despite her lack of interest in and painful past with sex. It is the conclusion of this story — Natsuko’s ultimate decision on whether or not to bring life into this world — that brings on the tears at the novel’s conclusion.

Kawakami makes each step of the story worth it for a reader with her lively, intrepid prose and measured use of stream of consciousness. As a result, each page is a thoughtful provocation of what it means to be alive.

The stream of consciousness literary style, pioneered by modernist writers such as Virginia Woolf and James Joyce, attempts to evoke the experience of thought on the page. After all, our lives are not defined by a series of events, but by a series of thoughts, feelings and perceptions of events. Kawakami’s beautiful and readable use of stream of consciousness opens up the possibility for a powerfully felt sense of empathy, not just towards Natsuko, but towards each emotion she feels and each experience she has.

View this post on Instagram

Bett, the translator of “Breasts and Eggs” along with Boyd, says that another distinctive element of Kawakami’s style is her willingness to revisit settings. “In the U.S., you go from one scene to the next — there’s a fierce progression,” Bett says. “Kawakami’s work often features return and revisitation.”

In some ways, it’s remarkable that this measured, sophisticated and highly literary book even made it to U.S. bookshelves. “It’s hard to imagine someone getting this book sold in the U.S.,” says Bett. “But, because Kawakami came as a known quantity in Japan, we were able to access a mode of fiction that would have otherwise been stopped by the literary gatekeepers.”

Kawakami worked at a hostess club herself before starting her career as a singer-songwriter. She turned to blogging to market herself at a time when the J-pop industry was consolidating, and her blog eventually grew to become extremely popular.

“I don’t have any formal training in writing, but I did blog frequently. I would write down the things I saw in daily life and my thoughts on feminism,” she told The Straits Times.

Kawakami is also known in Japan and abroad for her literary relationship with the arguably best-known living novelist in Japan, Haruki Murakami. Murakami famously said that Kawakami was his favorite young novelist, and Kawakami conducted a series of interviews with him from 2015-2017, published in the book “Haruki Murakami: A Long, Long Interview,” in which she confronted him directly about the portrayals of women in his work. “There’s a persistent tendency for women to be sacrificed for the sake of male leads. Why are women so often called upon to play this role?” she asked him.

But while her music is worth a listen, and her criticism worth a read, Kawakami’s true accomplishment is as a writer of the human experience. That is what has won Kawakami so many literary awards. That is what has catapulted her into the stratosphere of Japan’s most recognized and accomplished writers.

Kawakami says that she hopes readers will find in her work an expression of how the structure of society can be harmful to individuals, and that her readers will engage in deep questions about what it means to be alive.

“I think that many international readers have an image of Japanese people as being a little mysterious, a little friendly, that Japanese people are all wealthy, or all miserable with their jobs, etcetera,” Kawakami comments. “I would love for my international readers to start thinking about the lives of people that they don’t know, and even turn to face themselves and their own lives.”

Reading “Breasts and Eggs,” with its rich language, vivid characters and powerfully felt emotion, is the perfect spark for a reader to get into Japanese literary fiction.

“She reminds us why we read literature,” says Bett. “You come away thinking about how much there is to learn about the literature of Japan. Her writing is welcoming. It makes her kind of like a captain of literature.”