August 12, 2024

The True Story Behind the Hit Series Shogun: William Adams

The intrepid English adventurer who inspired the hit series FX's Shogun

By Trevor Kew

The historical drama series “Shogun,” produced by and starring Hiroyuki Sanada, tops the 76th Emmy Awards nominations with 25 nods, including Best Drama Series. The show has received outstanding praise from both critics and fans, currently ranking among the top series in television history.

“They had reached the end of the world,” writes Giles Milton in Samurai William (2002), his superb biography of William Adams (better known as Miura Anjin in Japan), the first Englishman to set foot in Japan. “A tremendous storm had pushed them deep into the unknown, where the maps and globes showed only monsters of the deep.”

Despite the fact that William Adams arrived on these shores half-dead from scurvy and starvation in 1600, it is surprisingly easy to identify with him, and even admire him. Nearly anyone who has moved to Japan has struggled with the language and cultural differences, not to mention the waves of loneliness, boredom and homesickness that inevitably wash over any stranger in a strange land from time to time. As a foreigner who has lived most of my adult life in Japan, I sometimes shock young new arrivals with my own intrepid tales of Japan before Google Maps and Google Translate. It was a time of paper Kanji dictionaries, visiting the koban for directions and pointing randomly at a menu hoping for the best.

Check out our map of real-life Shogun sites below:

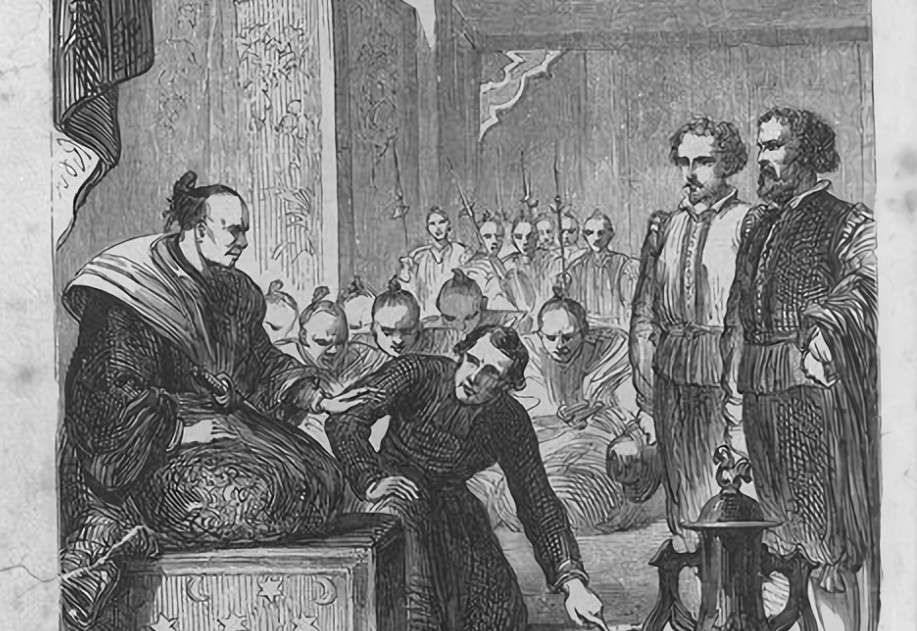

Upon First Arrival

What must it have been like for William Adams? In a time when many European maps of the world did not even include Japan, the only translation available was done via Portuguese or Spanish, and sending so much as a letter back to England was a matter of months or years. And yet, Adams defied the odds (and the scheming Portuguese) making a success of his life in Japan, learning Japanese, building two ships for shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu and being awarded the title of hatamoto, samurai retainer to the shogun, with his own lands and responsibilities.

It was the life of William Adams that inspired American writer James Clavell to pen his bestselling novel Shogun in 1975, which went on to be adapted into a five-part TV miniseries in 1980. This miniseries was so popular that nearly a third of American homes with televisions tuned in to its initial broadcast. Together, the miniseries and the novel helped spark an unprecedented swell of popular interest in Japanese history and culture in America, as well as the first boom of North American sushi restaurants.

On the surface, it’s not hard to see why. The stranger in a strange land has always been one of the most intriguing literary archetypes. Clavell uses his protagonist, John Blackthorne (very loosely based on William Adams), as his reluctant student of Japanese language and culture. Love interest Mariko acts as his translator and does her best to explain the many cultural differences that Blackthorne encounters.

Mixed Feelings

I’ve struggled to cut Clavell’s Shogun some slack over the years since first reading it when I moved to Japan in 2008 (unlike Adams/Blackthorne, my journey was mercifully free of storms, monsters, and starvation at sea). Obviously, it’s a work of fiction, so Clavell is free to take creative liberties with his story of John Blackthorne (an admittedly more exciting name than William Adams). Some of Clavell’s mistakes and misconceptions regarding Japan can probably be attributed to the limited information about Japan available in English in the 1970s, as well as Clavell’s own experiences as a prisoner of war in Java during World War II.

But it’s a hard novel to love. I’ve never been a fan of the omniscient narrator in fiction, where we see into the thoughts of every character. And the long didactic (and dubious) explanations of “the inscrutability of the Japanese mind” get old pretty fast. I’ve also never been a huge fan of the Pocahontas-style romance of Mariko and John Blackthorne, where the mystical local woman teaches the man that her culture is far deeper and more meaningful than his own.

Renaming Tokugawa Ieyasu, arguably the most significant and interesting figure in Japanese history, as Lord Toranaga is also irritatingly unnecessary, kind of like replacing William the Conqueror with John the Vanquisher or George Washington with Geoff Northington just for fun. The ending of the novel is the biggest letdown of all, with 1000-plus pages leading up to the decisive Battle of Sekigahara, only for the battle to be merely mentioned in a brief explanatory afternote. Imagine if Shakespeare had ended Richard III in Act 4 and just left out the whole “Kingdom for a horse” bit.

Retelling the Story

And yet I’ve always believed that there was a better story waiting there, ready to be told. So when FX released their 2024 TV series adaptation of Shogun, I was pleased to see that the creators of the series had read books like Giles Milton’s Samurai William as well as conducted thorough research into the clothing, language, architecture and politics of the late Sengoku period of Japan (my only slight quibble, as a former Vancouverite, was that the trees, mountains and sea made it obvious that the series had been filmed in British Columbia, not in Japan!). The Japanese cast was composed of many of the finest actors in the country, most with extensive experience in jidaigeki (Japanese historical period dramas), including the incomparable Hiroyuki Sanada, who played Toranaga. Mariko was played by the excellent Anna Sawai, who perfectly inhabits a character caught in the middle of many difficult situations. Cosmo Jarvis also strikes the perfect balance of stubbornness and openness as Blackthorne.

Highlight of the Show

Best of all, however, was the portrayal of the relationship between Blackthorne and Lord Toranaga, which veers from suspicion and manipulation to tolerance and possibly even friendship. The scene where Blackthorne is asked to teach Toranaga to dive off a boat perfectly encapsulates the way that these two men from such different cultures and social classes come to find one another so incredibly interesting. It makes me wonder what the conversations between William Adams and Tokugawa Ieyasu were like in real life. Maybe they were limited and formal, but I’d like to believe that there was at least something of the connection that we see between Blackthorne and Toranaga in Shogun.

When Japan’s period of self-enforced seclusion came to an end in the mid-19th century and outsiders were allowed back into Japan proper for the first time in over 200 years, foreign visitors were astonished to find that villagers near Adams’ old fief of Hemi still told stories about the English samurai Anjin-sama who had once presided over their lands so long ago. That his memory persisted then and today, in a TV series made more than 400 years after his death, is a testament to the enduring appeal of his unusual and fascinating story.

Places to visit in Japan related to Shōgun

While remnants of the Japan of Tokugawa Ieyasu and William Adams are few and far between these days, there are a few places left where one can go to feel the faint whispers of this distant past. The graves of Adams and his Japanese wife can be visited atop the hill of Anjinzuka near Yokosuka, close to Adams’s feudal fief of Hemi. Most travelers zip past the narrow valley where the epic Battle of Sekigahara (read more in Sekigahara) took place between Tokugawa and Ishida (albeit slightly before Adams arrived in Japan). But if you stop off, there is an excellent museum, as well as a walking tour of the battlefield including Black Blood River, where the heads of vanquished foes were washed before presentation to Tokugawa (not far, amusingly, from the Sekigahara Lawson).

For those seeking a unique blend of history and luxury, stay a night at Hoshino Resorts Kai Anjin. Named after Adams’s Japanese name, the hotel integrates his legacy into its offerings. The “Anjin Journey” experience program immerses guests in the era of William Adams, showcasing the navigational wisdom of his time through a story-driven short film. Additionally, guests can savor Japanese kaiseki cuisine crafted from local Izu ingredients, enhanced with British elements inspired by Adams’s background.

Those headed to Kyushu will find the tiny Dutch Edo period enclave of Dejima in Nagasaki fascinating (or the short-lived English trading post in remote Hirado that Adams frequently visited). And Shimabara Castle, where the forces of the third Tokugawa shōgun (Ieyasu’s grandson) crushed the final Catholic uprising in 1637, contains an illuminating exhibit on the kakure kirishitan (hidden Christians) on its second and third floors.

A Dive into the Shogun’s Life

My pick of the bunch, however, is the Tokugawa Art Museum in Nagoya, which has a large collection of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s personal belongings. A slow stroll through the museum offers an astonishingly personal glimpse into the shogun behind Shogun’s life, including the toys he played with as a child hostage, the underwear he wore under his gorgeous robes, and the calligraphy brushes that he preferred to his swords. I found it quite human how Ieyasu had long tried to imitate the letters of a long-dead samurai whose writing style he admired. And there was one scroll, framed majestically on the wall, that was nothing more than a busy travel itinerary (Kawagoe on Friday, Edo on Sunday…that kind of thing), a reminder that in essence, Ieyasu was not so different from our own busy bureaucratic leaders of today.

You can also visit the East Gardens of the Imperial Palace, where Tokugawa held court when it was Edo Castle. The original buildings are gone now, but as you walk through the gates past its mighty walls, it is perhaps possible to experience something of what William Adams must have felt when he was summoned to meet the most powerful man in Japan all those centuries ago.