Thanks to being an American military spouse, I’ve now lived abroad twice. Of the last 10 years, we’ve spent three in England, almost five back in my native Ohio, and a little more than a year here in Tokyo. Getting thrown repeatedly into alien environments has taught me a few things about myself.

My most valuable lesson? Screw shyness. When I move to a new place, I have to figure out a way to play extrovert—at least long enough to make a few friends who can support me over the next year or two … or three.

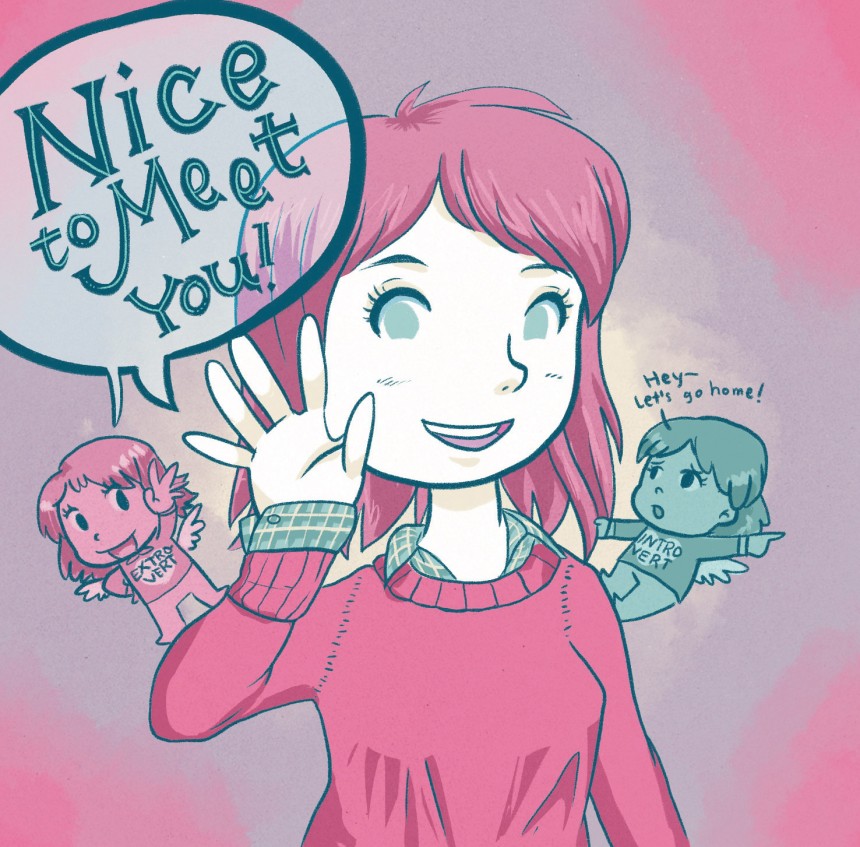

I say this as someone who hovers on the borderline between introvert and extrovert. People who met me in the last five years might say, “Introvert? You? Nah. You’re that friendly woman who always says ‘hi’ and invites half-strangers to coffee or to check out a new restaurant.” I’m that person—in large part because I’ve learned to be that person.

My first real international move was from Ohio to England as a 30-year-old newlywed. My husband was a freshly minted officer in the United States Air Force, and we were giddy at the prospect of spending three years at RAF Mildenhall. After two months of staying in hotels on base, we gratefully moved to a rental home 45 minutes away in beautiful Cambridge.

Sound great? Sure—except I had no friends. And no job either. I should have gotten out of the house to meet new people, but instead I stewed. I slept in late; I puttered for hours on my laptop, keeping up with friends from home. From the safety of my couch, I watched way too many reruns of American sitcoms each afternoon. Even after I rallied enough to start volunteering part-time in the administrative offices of a charity for the homeless, I was crippled by shyness, unable or unwilling to invite my new colleagues out to socialize.

In short, I was miserable. Maybe not quite clinically depressed, but I wasn’t in a good state of mind. Six months in, I returned to the U.S. for a brief visit. The trip was enough to shake me out of my stupor. The jealous comments of friends and family reminded me that I was truly lucky to be handed an exciting adventure, a chance to live abroad. I was a fool to waste that opportunity.

When I returned to England, I made some serious changes. I invited co-workers to dinner. They accepted; we had fun. My husband and I signed up for a wine-tasting course. More dinner and drinking invitations ensued. I took dance classes and twirled and sweated alongside other expats from Portugal and Ireland. I applied for full-time jobs, threw on a façade of self-confidence, and found employment at the University of Cambridge in a PR role that required buckets of extraverted behavior.

My state of mind improved dramatically. No more long, lonely hours whiled away in silence. No more frustrated tears because I’d gone another day with barely any human interaction. Sure, I still had occasional rough days. But I shudder to think what my life would have been like if I’d never broken out of my shell.

It’s a lesson I’ve chosen not to forget. I’m more than a year into my life on a U.S. military base here in Japan, but it only took a few weeks before I started forming new bonds. Many of us were new at the same time, which helped—but so did my willingness to smile and extend a simple invitation to hang out. Our new friendships have proven invaluable in helping to make our time here a fulfilling, enjoyable experience, instead of just one more box to tick on my husband’s career trajectory.

Life is short. I owe it to myself and to the people I love to live as happy a life as I can muster, in the here and now. I won’t bide my time anymore, hiding away, hoping that somehow, magically, I’ll form a network of relationships to soften the stresses of living someplace new. Shyness is simply no longer an option.