July 28, 2017

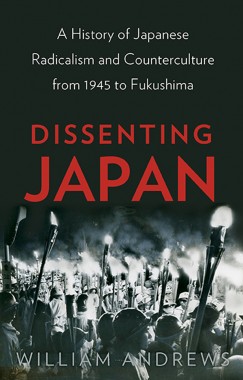

Book Review: Dissenting Japan

The rising tide of Japanese ultra-nationalism

No cliché about Japan is as persistent, nor as totalizing, as the one that marks the country as a wonderland of orderly homogeneity; a place where harmony reigns, conflict is avoided and the collective will is prized above all else. Flowing from this is another persistent trope: Japan is apolitical — the vertical, frictionless structure of Japanese society means that political discontents and conflicts simply do not exist.

Of course, this is nonsense. In his book Dissenting Japan: A History of Japanese Radicalism and Counterculture from 1945 to Fukushima, William Andrews masterfully explodes this lazy shibboleth, recounting the struggles of the post-war New Left to do so. The flipside to the leftist radicals, however, is the ultranationalist far-right, who are never quite out of sight in Andrews’s narrative. They are a lurking presence in Japanese politics that — woodlouse-like — seem to weather all storms. Indeed, today, it is the far-right who are the most visible on the nation’s streets and who enjoy a frightening symbiosis with the very highest levels of the Japanese state.

These ultranationalist groups, collectively known as the uyoku dantai, aren’t hard to find. On weekends and public holidays they emerge on the streets of busy commercial areas up and down Japan, blasting imperial tunes from their customized “sound trucks,” cosplaying as World War II fighter pilots, and lecturing the passing throng who generally avert their eyes and do their best to block out the cacophony. Throughout Japan there are roughly 1,000 of these groups, and when numbers were last tallied in 2014, overall membership totalled around 100,000 individuals — predominantly male and aging.

The uyoku dantai are disorganised, fractured and lack complete ideological uniformity, but they are loosely structured by a handful of core ideas. This belief system revolves around the supremacy of the Emperor and the righteousness of the nation’s imperialist past. They believe Japan was scapegoated in the post-war peace accords and deny the validity of wartime atrocities, as well as the U.S.-drafted constitution. To regain its greatness, their narrative goes, Japan should reassemble its military (restricted by the constitution) and reject foreign influence. Anti-Chinese and Korean racism, anti-communism, anti-feminism and a belief in traditional values are also commonalities.

Through Flick Creative Commons. User Jeffrz

The spiritual home of these groups is Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo. Here, Japan’s war dead from the Meiji Restoration onwards are deified, including, crucially, Class-A war criminals responsible for some of the Pacific War’s most heinous atrocities. The shrine is indelibly linked to the far-right’s favorite themes of militarism, sacrifice and greatness, all fleshed out in the adjoining museum which offers a frighteningly revisionist version of Japanese military history.

Uyoku dantai are a fixture at Yasukuni Shrine, often to be found parading around in full reenactment mode. More worrying are the repeated visits to the shrine over the years by senior politicians, all too aware of the shrine’s contentiousness and symbolism. These visits have enraged China and Korea, who view them as acts of colossal disrespect. This, however, is but the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the coziness between the far right and Japan’s political establishment.

Footage appeared online depicting the children of an Osaka kindergarten singing along to a military song which included the line: “We want China and South Korea, which portray Japan as a villain, to be repentant, we’ll root for Prime Minister Abe.” Further investigation revealed the full extent of the preschool’s nationalist and xenophobic curriculum, reminiscent of prewar Japanese schools, as well as the embarrassing fact that Akie Abe, the wife of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, was an honorary principal of the school and had donated funds to help set it up. An inquiry also found that the school’s founders had purchased government-owned land below market price, fueling speculation about murky deals between government officials and nationalist groups.

To some, the revelations came as no surprise. Shinzo Abe, along with the majority of his Cabinet, has ties to various ultranationalist groups, most prominently with Nippon Kaigi, a nationalist non-party political grouping which opines the necessity of preserving Japan’s “beautiful traditional national character,” revising the “masochistic” school curriculum, opposing “the rampant spread of gender-free education” and adopting “a new constitution suited to a new age.” 280 politicians — or 40% of the entire Diet — belong to the parliamentary Nippon Kaigi Discussion Group, and the group has 250 offices across the country and some 38,000 fee-paying members.

Through Flickr Creative Commons, by Junpei Abe

Although expressed with a degree of deftness, the guiding beliefs of Nippon Kaigi align almost perfectly with the extremist groups shouting from the street corner, the crucial difference being that where the footsoldiers of the uyoku dantai are seen as peripheral and are largely ignored by the general population, the dark-suited membership of Nippon Kaigi enjoy a firm grip on the levers of power.

This symbiosis between the ultranationalist right and the upper echelons of political power is in many ways nothing new. Indeed, Abe’s grandfather and former Prime Minister, Nobusuke Kishi, notoriously enlisted the help of right-wing, yakuza-connected heavies in 1960 to protect visiting President Eisenhower from left-wing protesters at Haneda Airport. Kishi earned the dubious nickname “America’s favorite war criminal” for his role in expanding the U.S.’s military presence across the Japanese islands and fed off the resentment of the far-right to embark on a crusade to revise the nation’s constitution and remilitarize.

Kishi failed to carry out his mission, thwarted by increasingly combatant and well-organized left-wing student radicals. His grandson, however, seems determined to finish what he started. Since becoming prime minister in 2012, Abe has been steadfast in his commitment to force through legislation that would allow the post-war pacifist constitution to be amended. The changes hinge specifically on Article 9, the clause which puts limits on the Japanese military and prohibits the country’s right to wage war. To do this, Abe requires a two-thirds majority in both legislative houses and to win a referendum on the issue, which he aims to accomplish by the time of the Tokyo Olympics in 2020.

Abe’s plan and rhetoric of “new-nation building” echoes the deeply held desires of the nationalist right ever since the constitution was put in place in 1947. The document represents Japan’s defeat in the war, the loss of its empire and its perceived subservience to foreign nations; to get rid of it is to begin the project of restoring Japan’s “beautiful traditional national character.” Despite fierce resistance in some sectors, Abe’s government enjoys majority approval in polls, giving it the confidence to push through its controversial agenda. The “anti-conspiracy” bill is another expression of Abe’s remodelling plan. The bill, which came into effect on July 11, gives sweeping new powers to Japan’s security services, making 277 offences subject to conspiracy charges. Ostensibly designed to curb the threat of terror, critics argue that it is tantamount to the establishment of a surveillance state.

What the right sees in the past is colonial glory, national cohesion and, importantly, economic stability.

The extreme rightward bent of mainstream Japanese politics doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it mirrors the global rise of a newly heartened far-right, best seen in the ascendency of Donald Trump to the US presidency. Like Abe and the uyoku dantai, figures like Trump are fundamentally reactionary: a mythologized, artificial and exclusionary recollection of former glory is used as justification for regressive and damaging policy; the idea of the nation is foregrounded and minorities are rejected out of hand. The braying nationalist right is driven, in essence, by nostalgia for an imagined past.

What the right sees in the past is colonial glory, national cohesion and, importantly, economic stability. Like the majority of countries in the Global North, Japan’s economy is stuck in terminal decline after decades of rampant neoliberalism. Poverty is on the rise, wealth inequality is ever-widening and the ruling Liberal Democratic Party seems to have no antidote. Although all indicators point to the fact that Abe and his colleagues in government believe wholeheartedly in their crusade, it is nevertheless a smokescreen covering the gaping void at the heart of their politics; a nationalist blanket concealing their paralysis in the face of a failing economic order.

As described in Dissenting Japan, the post-war period saw the emergence of an energized and proactive left-wing in Japan. It was fraught with internecine conflict and marred by controversy, but its very presence offered an alternative vision of how to organise society and vigorously opposed the nationalist right at every turn. Nothing on this scale exists today. Representatives of the Old Left, the Japanese Communist Party, currently hold 21 seats in the House of Representatives but are largely impotent and New Left groups like Zengakuren (All-Japan League of Student Self-Governments) and Chukaku-ha (Central Core Faction) are but shadows of their former selves. Some believe hope does come from the various anti-fascist groups that are active in opposing the worst excesses of extremism, from the flurry of interest in anti-nuclear issues in the wake of the Fukushima disaster and demonstrations such as the recent anti-Abe march in Shinjuku, but these groups and protests are by their very nature always on the back foot, always taking a defensive stance. If Japan is to change its course, a positive vision of the future, one based on inclusion and equality, will need to be articulated.

–

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of Japan Partnership Co. Ltd. or its partners and sponsors.