February 4, 2026

The History of Patriarchy in Japan

And how history rewrote women out of power

Every few months, a familiar warning resurfaces in Japanese politics: “tradition,” we’re told, must be protected from modernity. The latest came from Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, who wrote on Facebook:

(今を生きる日本の政治家として

何より大切だと考えることが2つあります

ひとつは、男系で受け継がれてきた皇室を守り

皇室典範を改めていくこと…)

It sounds authoritative, but it omits the most important fact: the “male line” as we know it is modern. Yes, today’s imperial succession is strictly patrilineal, but that framework didn’t guide the earliest centuries of the Japanese state. Treating it as ancient obscures a much more complicated history.

Are trains in Japan safe for women? Check out our article on Women-Only Train Cars in Tokyo.

The Unbroken “Male Line”

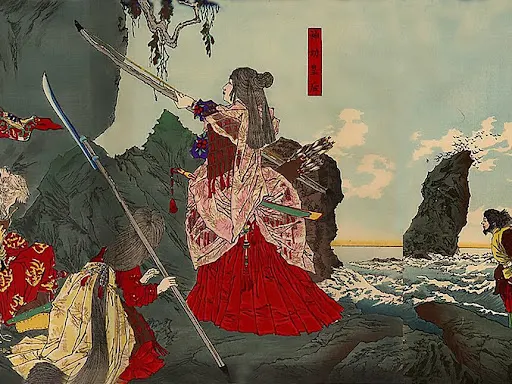

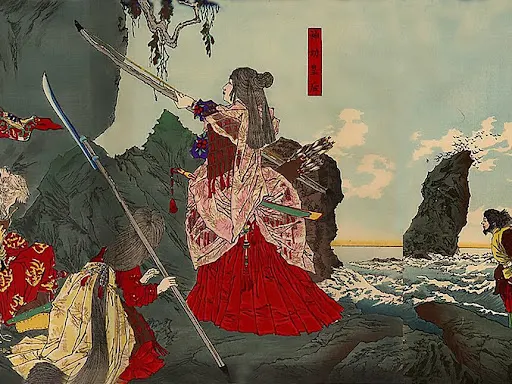

For generations, people have spoken as though Japan’s supposed “unbroken male line” were carved into the archipelago itself, timeless, innate, uniquely Japanese. But the deeper you go into the historical record, the more that story unravels. Early sources didn’t treat gender as the key to legitimacy. Women ruled, issued laws, built capitals, corresponded with foreign courts and governed with full sovereign authority.

The shift toward male-only succession was gradual and political, not cultural destiny. And it didn’t crystallize until the modern era. When the Meiji government wrote the first male-only rule into law in 1889, it wasn’t preserving an old truth; it was creating a new one and projecting it backward. The current Imperial House Law of 1947 preserves that structure, which is why Princess Aiko (Emperor Naruhito’s only child) is barred from the throne today.

This matters because the “unbroken male line” is often framed as a sacred inheritance Japan has safeguarded since antiquity. In reality, it is a recent legal invention. Even so, conservative politicians still invoke a “male line since Emperor Jinmu,” a narrative based on reading the past through concepts those eras never used. And with only a few male heirs remaining, the modern rule is colliding with practical reality, at a time when public support for female succession continues to grow.

Before the Patriarchy

Centuries before Japan defined rigid gender roles as “tradition,” one of its earliest known rulers was a woman. In the third century, the shaman-queen Himiko ended decades of internal conflict and governed the people of Wa. Chinese envoys documented her diplomacy and spiritual authority and recognized her as the “Queen of Wa.” Yet she is absent from the Nihon Shoki, Japan’s earliest official history, surviving mainly because foreign writers recorded her as she lived.

The Nihon Shoki does describe other women who ascended the throne as tenno, a title that remained gender-neutral until modern times. Empress Suiko, Jito, Genmei, Gensho and Koken shaped early state formation, issued codes, oversaw diplomacy and ruled in their own right. Today’s history textbooks often describe them as placeholders until a male heir matured, but that interpretation reflects modern assumptions more than historical evidence. Contemporary records show them ruling because they were suited to rule, not because of (or despite) their gender.

Historian Hitomi Tonomura notes that early Japan didn’t imagine royal blood as something that flowed only through fathers. A ruler’s legitimacy drew just as much from their mother. Before the late eighth century, there was no fixed rule requiring the throne to pass through men.

And the numbers are striking: between 592 and 720 (one of Japan’s most formative eras), six women ruled across eight reigns. Seven men ruled in that same window. In practice, a woman on the throne was neither unusual nor controversial.

Cultural Power in Women’s Hands

Women’s influence stretched far beyond politics. They defined classical literature: Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shonagon still stand among the world’s most influential writers. Women shaped spiritual life as miko and ritual specialists, documented court society, critiqued politics and wrote with a perspective that still informs how Japan’s past is understood.

In other words, early Japan was not built on the idea that men had to lead. It was a society where women held authority across government, culture and religion. So, how did Japan become a country where female emperors are prohibited? How did “tradition” come to justify excluding women from roles they once regularly held?

The Imported Order

The answer lies not in ancient custom, but in outside influence.

By the seventh and eighth centuries, the Yamato court looked to China and the Korean kingdoms not just for inspiration but for recognition. To be treated as a legitimate player in a Sinocentric world, Japan adopted many of Tang China’s political structures. Law codes, court ranks, temple systems and diplomatic rituals. With these came aspects of Confucian ideology, including hierarchical family structures that privileged male authority.

Buddhism added another layer: some sects taught that women needed to be reborn as men to reach spiritual liberation. Women continued to serve as mediums and practitioners, but they navigated an imported ideological framework that complicated their authority.

None of this immediately banned female rulers. But it shifted elite expectations. Continental-style hierarchy became associated with political legitimacy. Over time, the once-unremarkable presence of female rulers became harder to justify within this imported framework.

Still, the break wasn’t complete until the modern state wrote it into law.

The Modern Myth

By the Meiji period, the political vocabulary for female sovereignty had already narrowed. But it was the modern state, not ancient custom, that sealed the door shut. The 1889 Meiji Constitution established the first legal ban on female succession, adopting a strictly male-line system drawn from continental theory. Once the rule was set, earlier history was reread through it.

This backward reinterpretation was powerful. As Tonomura notes, Meiji thinkers dismissed earlier empresses as “intermediary” rulers defined by shamanistic mystique, a framing that reflects their own gender biases far more than historical reality. A male-only monarchy needed a legitimizing story, and so one was constructed.

The Meiji era produced many other institutions now defended as timeless traditions. The koseki system, requiring a married couple to share a surname, dates to 1875. The “Good Wife, Wise Mother” doctrine emerged from modern nation-building, not ancient practice. Yet today, these nineteenth-century policies are often cited as evidence of immutable Japanese values.

This is the modern myth: gender roles shaped in the 19th century are presented as remnants of an ancient past. In truth, much of what is now defended as “tradition” reflects the priorities of a young modern state. Patriarchy in Japan wasn’t an unbroken legacy. It was a construction.

And it worked. By the 20th century, the legal and ideological infrastructure of the Meiji state made the earlier era of female rule appear anomalous, even impossible. The eight empresses of early Japan became footnotes. Male-only succession became common sense.

What the modern era produced wasn’t continuity, but the illusion of it.

This article appeared in the Winter 2025 Print Issue of Metropolis, themed “Tradition.”

For a deeper look into the patriarchy in Japan, read our article Are Japanese Men Afraid of Independent Women?