June 26, 2018

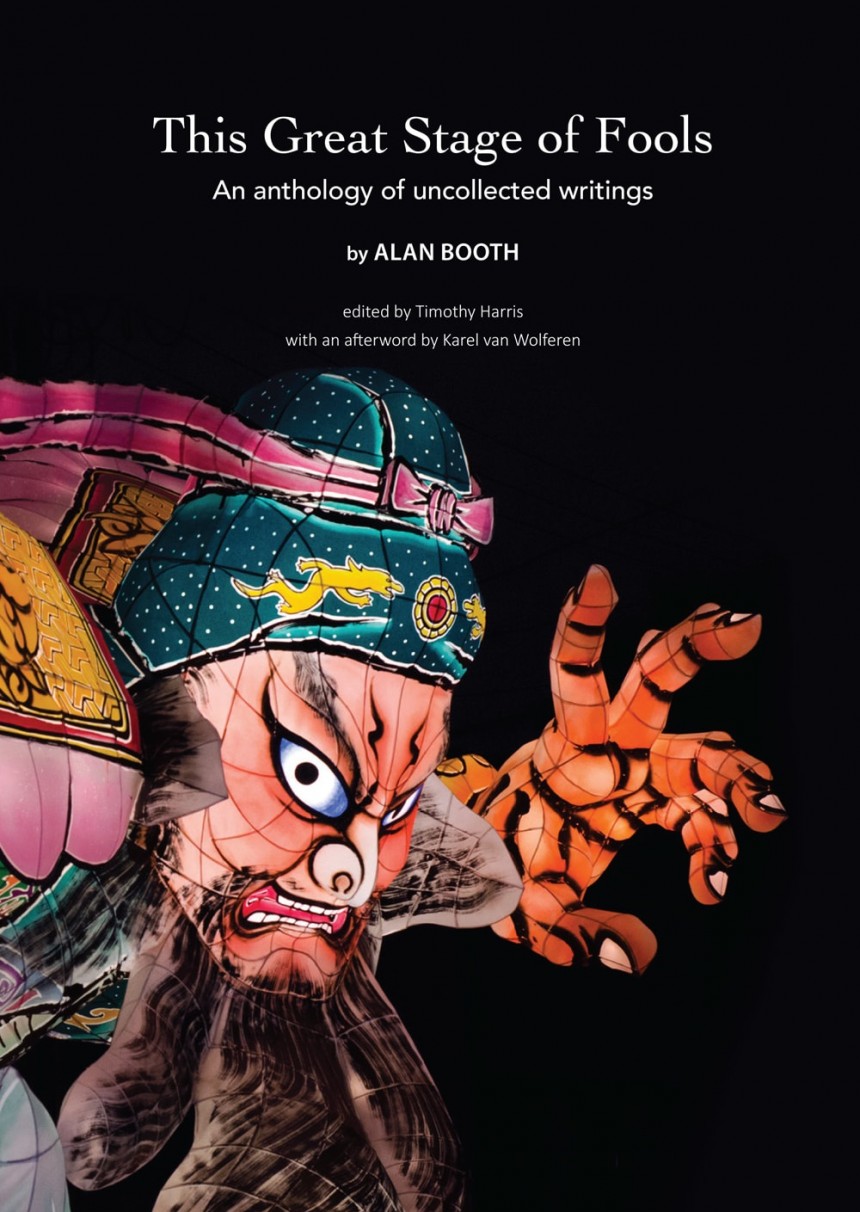

This Great Stage of Fools

An anthology of Alan Booth's uncollected writings on Japan

By Paul McInnes

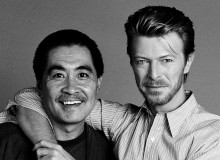

Alan Booth will be remembered for supreme journalism, his Japanese film reviews for the Asahi Evening News and his seminal travel book “The Roads to Sata.” Often mentioned in the same breath and paid as much reverence as Ian Buruma, Alex Kerr or Will Ferguson among many writers and readers in Japan, Booth’s writings are as critical and necessary as ever before.

In this new book of uncollected writings, grouped together and edited by his friend and peer Timothy Harris, Booth’s sharp wit, acerbic humor and general bonhomie come to light. It’s clear, especially in “Roads Out of Time,” that Booth was a psychogeographical writer much in the same vein as Will Self, Iain Sinclair and W.G.Sebald, but with more beer and hot spring baths.

“Roads Out of Time” is one of the many gems in this new collection. Booth’s empathy and humanism seep through his often very comical writing. Fleeting encounters with Shikoku locals, bloodied and blistered feet, random karaoke adventures and the simple pleasures of a hot bath after a long day’s trek make for fascinating reading and are invaluable glimpses into rural Japan in the 70s and early 80s. With brilliant lines such as, “Everything on earth looks better after two bottles of beer and an eight-inch sausage,” neatly juxtaposed with more serious paragraphs in the wake of a devastating earthquake and tsunami in Akita Prefecture:

“As news came in over the next few days, it transpired that the highest waves had reached a height of fourteen meters…In its wake it left one hundred and four dead, though the early, hesitant figures merely counted people “missing.” I was fascinated, too, by the blithe shrugs of my fellow diners in the restaurant. They listened to the details as intently as I did, but nine hundred miles by crow’s flight separated them from the flooded streets and wailing mothers, and that “one family” to which many Japanese say they belong seemed suddenly a fiction of airline magazines.”

Other sections of the collection detail Booth’s fascination with drama such as a segment of theater reviews and smaller travel essays detailing Japan through local festivals and folk songs associated with particular places. His film reviews and essays, widely celebrated at the time, reveal a deep-rooted passion for Japanese film and culture and, as well as being wildly funny, detail his chance encounters with film legends such as Teinosuke Kinugasa, whom Booth met on New Years Day at Kiyomizu Temple in Kyoto. His review of cinematic flop Hai Tiin Buugi is one of the funniest reviews you’ll ever read with the opening sequence:

“Aren’t you making a mistake?” asked the lady at the box office when I slid my money under the glass.

“Yes,” I sighed, “almost certainly.”

Booth, then, left a considerable legacy when he sadly passed away at the premature age of 46 due to cancer. The last part of the book includes Booth’s own essays dealing with his illness in which he never lets up his comical musings on life and celebration of humanity. Booth’s writing and life had a huge impact on many people, including Harris who does an admirable job introducing Booth’s work. “This Great Stage of Fools” is a great introduction to Booth’s writing and also a wonderful literary present for those who fell in love with his earlier books and for those whose lives he touched along the way.

“This Great Stage of Fools” by Alan Booth, edited by Timothy Harris, with an afterword by Karel van Wolferen.

Available from publisher Bright Wave Media, Inc. http://brightwavemedia.com/booth.html

It is also available at the Tsutaya Bookshop in Daikanyama.

Metropolis interviewed editor of “This Great Stage of Fools” – Timothy Harris. A friend and peer of Booth, he talks about Booth as a person, his work and his legacy.

Metropolis: What was the process of collecting the pieces in this book? How long did the process take?

Timothy Harris: Well, all in all, the process has taken 25 years, since I couldn’t find a publisher until recently. I am Alan’s literary executor, and I kept most of his journalism—faded and yellowed newsprint, mostly. I wanted to publish the book soon after his death, and so knew pretty well what I wanted to do 25 years ago. I particularly wanted to print the most interesting of the film reviews and the articles on festivals. The ordering of the articles in that way was more or less in my mind from the beginning. The articles on folksongs for some reason I didn’t have, and I was alerted to their existence only very recently (last year), and thought they would come best after the festivals: it made a nice pairing. Then there was the splendid interview with Takahashi Chikuzan, whom I had discovered before I met Alan. We were both delighted to find that we were both fans of his: he was a very great musician. Then there was the Shikoku walk. And I wanted to finish with the final articles he wrote about his fatal illness.

Preparing things also took a long time: I had ignorantly assumed that with modern copying techniques and computers it would be a simple matter to put newsprint into another format. It is not. It all had to be copied and turned into PDF files (this was done by a good man in Singapore), sent to me, and then I painstakingly transferred the copied newsprint bit by bit onto Word, correcting things (since the copies were often unclear and there were a lot of mistakes) and putting everything into a proper format for publication. The folksong pieces I simply typed out myself when I got them (they were from a magazine, and so there was not the problem there was with the newsprint).

M: What do you think younger readers (who weren’t alive during Booth’s lifetime) will make of this book and his other work?

TH: I don’t know what younger readers will make of his work – everybody is attracted (or un-attracted!) by different things. But I hope that they will find the intelligence, incisiveness, wit and energy of the writing as exhilarating as I do. As well as the great sensitivity, the insights, and the melancholy that one often detects underlying his pieces. The descriptions in the festival and folksong pieces are extraordinarily evocative. I do notice a tendency for people – male people, I should say! – to be attracted (or put off, as certain older ‘Japan hands’ I knew definitely were) by the gallons of beer consumed, and Alan’s sometimes rather bloke-ish humour: well, those things are there, but there is a great deal more besides, and that great deal more is far more important than the beer and that side of Alan’s humour (which on occasion irritated me as well). And there is a lot that is rightly serious. It’s a pity that these things should often be overlooked.

M: What was Alan like as a person? You knew him well—he comes across as very funny and bright, but what did you make of him when he was alive?

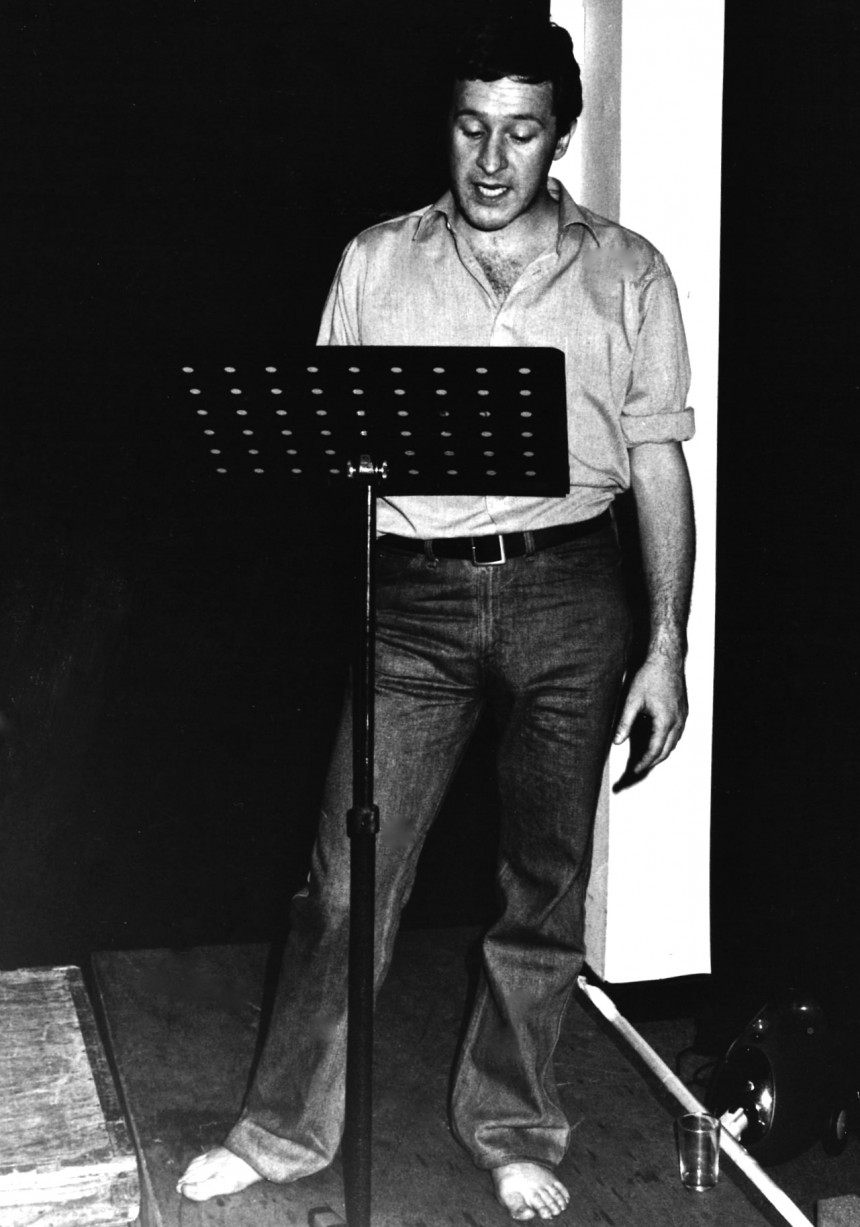

TH: I think I have said everything I want to say on that score in the introduction—though I could add that Alan was a wonderful companion and wonderful to work with as an actor. And also a wonderful writer to work with as an editor—it was a privilege to work with someone who took such care with his writing.

M: What do you think his legacy as a writer will be? How does he rate alongside Kerr, Richie, Buruma etc…?

TH: His legacy as a writer—well, I don’t know how to answer that. Who can know what somebody’s legacy might be? His importance, in all his pieces, it seems to me, is that he looked at Japan in a wonderfully fresh and honest way and in doing so shattered what I call the “aesthete’s view” of Japan in my introduction, as well as any number of cliches about Japan and the Japanese. Shattering these things was not something he particularly set out to do; he didn’t set out to be different from those who had written about Japan before him (the desire to be different for the sake of it seldom leads to interesting work). The shattering was a kind of by-product of the freshness and honesty of his approach. He looked at things as directly as he could. He was not interested in all the tired cliches that had been handed down.

I don’t want to compare him with other writers on Japan. I shall simply say that in terms of the things he wrote about and his approach to them, I think he was by far the best writer of his generation and a far better writer than many writers of other generations. I do NOT want to name names!

M: What is your favorite piece of Alan Booth’s work and why?

TH: There are many favourite pieces. I like “The Roads to Sata” for its freshness of vision.

I love the insights one comes across in the film reviews. For example, this sentence in which he talks about the children in his view of Doro no Kawa: “There is in these faces a frightening wealth of experience, cunning, innocence and understanding, and that Oguri has tapped this wealth so so completely is an achievement that vies with the film’s extraordinary technical excellence.” And one comes across sentences such as this in the review of Hai Tiin Buugi: “Eighteen months ago, when they made their screen debut, the idol of the trio was Toshihiko Tahara, whose pre-puberty James Dean pouts provided the film with its climaxes and the schoolgirls with theirs.” It is a wonderfully funny sentence not simply because of what it says, but because of its wonderful rhythm and construction: the alliteration (on ‘p’) that reproduces in sound the action of pouting, and the punch of that exceedingly climactic ending. He had a wonderful ear.

But it is the quality of the judgements that is so impressive. If I were to single out one article in which a fair and brilliantly argued judgement is made (there are many), it would be the review of Akira Kurosawa’s Ran. Alan’s judgement seems to me to be unanswerable. Certainly, the only attempt I have come across that tried to take issue with it—Donald Richie’s—was singularly unconvincing.

I also like very much the festival pieces and the folk-song pieces. Again there are these wonderfully-shaped, evocative sentences. For example, in “Winter Hats,” there is this: “There is no snow, which annoys some of of the cameramen, but the glitter of the hard ice pleases most of them, cracking and snapping under the dancers’ feet.” Ah, I can’t really pick things out, but the pieces on the Sanja Matsuri and the Oga Namahage, as well as the Osorezan Dai-Matsuri strike me as particularly fine.