February 25, 2010

Big Babies

Asashoryu’s retirement exposes the cracks in sumo’s management

By Metropolis

Originally published on metropolis.co.jp on February 2010

In my nine visits to the Ryogoku Kokugikan to watch sumo, the most enthralling matches always involved yokozuna Asashoryu. The Mongolian’s fiery spirit and trademark rikishi belt-slap were guaranteed to intimidate his opponents and raise the roof. With his recent resignation, after reportedly breaking a man’s nose in a drunken brawl in Nishi-Azabu during the January Grand Sumo Tournament, Japan’s national sport has lost its most charismatic grappler.

At a press conference after the resignation, fellow yokozuna Hakuho was visibly distraught, sobbing about how his foe had “pushed me to greater heights.” That they’ll wrestle no more will inevitably result in a drop of interest in sumo. For the blame-passing Japan Sumo Association, I can’t say this outcome is undeserved.

If the reports about the assault are true, then Asashoryu was absolutely right to quit. However, it was hard not to feel a sense of déjà vu when JSA head Musashigawa commented afterwards that his organization “will work together to make sure there is no recurrence of this.” Surely the JSA hasn’t forgotten about the young Russian sumo brothers Wakanoho and Hakurozan, who were nabbed for buying marijuana in a Roppongi club in 2008? Why was Asashoryu allowed to go partying during a tournament in the first place?

When Asashoryu announced his resignation, his stable master Takasago—who by sumo rules was ultimately responsible for him—was asked by assembled press what his deshi (apprentice) had been like. The answer came in a smug glance at his pupil, a smirk, and the remark: “Like this.”

Takasago can’t be blamed for growing tired of Asashoryu’s many faux pas, but his laidback attitude shows a lack of contrition about his own shortcomings. Only a few days earlier, with news of the scandal hanging over him, he had returned to his stable drunk after going to an izakaya with some of his pupils—hardly the mark of a strong leader.

In his own sumo career, Takasago reached the second-highest rank of ozeki; by comparison, Asashoryu stands as the third greatest yokozuna on record, with 25 Emperor’s Cups to his name. Considering the disparity between their achievements, it must have been hard for the master to command full respect from his pupil.

There’s a simple answer to problems like this: the JSA should consider assigning stable masters to suit the circumstances of each wrestler. Yes, Asashoryu’s behavior has been pretty appalling, but I doubt he would have been nearly as brazen had he been placed under the guidance of former yokozuna Chiyonofuji or Takanohana.

Sumo is a unique, ancient sport that has maintained its ritualistic code of conduct remarkably well. But the JSA is foolish to assume that 21st-century wrestlers will automatically adhere to the same code in their private lives. Sumo should follow the lead of other sports when considering young athletes with high profiles and money. Educating wrestlers in how to protect themselves from media pratfalls should be high on the JSA’s agenda, if only to stop the sport—and the JSA itself—from looking even more farcical.

Just before Asashoryu’s final scandal unfolded, the association was going through an election shakeup. Reformist Takanohana broke away from the Nishonoseki faction of stable masters to run for a director position, despite being deemed too young. Against the odds, he was elected to the board.

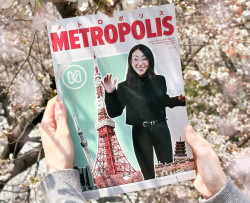

Illustration by Ben Turner

The decision divided opinion, but more embarrassingly it smashed what little democracy there was in the JSA’s voting system. While some saw Takanohana’s election as a fresh start, others openly pointed fingers at those who had voted him in. Confessions were made, and a resignation offered–by Ajigawa, who admitted that he had voted for Takanohana instead of his usual faction leader.

A member of the JSA offered to resign merely for exercising his democratic rights, but in the three years I’ve been following sumo, not once has anyone in the organization taken full responsibility for their mismanagement of wrestlers. Not over Asashoryu, not over Wakanoho and Hakurozan, and not even following the death of 17-year-old Takashi Saito after hazing by his peers. Takanohana’s election is a positive outcome considering the headaches sumo has had recently, but I’ll say to the optimists: don’t get your hopes up too quickly.

Everyone likes to watch a bad boy, and no Asashoryu equates to boring sumo. His resignation is the climax of a series of embarrassments in which the JSA has consistently shifted the blame. For the sake of the fans, let’s hope they start cutting problems at the root and taking action in their own ranks first. A vote for the next scandal’s fall guy, anyone?