June 27, 2018

Book Review: The Seasonal Beauty of Japanese Cuisine

A guide to the four seasons of Japanese food

Japan is well known for its celebration of seasons, particularly in its food. Dishes featuring ingredients particularly fresh and in season are a defining feature of washoku, Japan’s World Heritage-listed national cuisine.

It is also often said that Japanese dishes are a feast for the eyes as well as nourishment for the body, as each course is beautifully presented in a dish of a shape and color that sets off the food it contains, often garnished with a seasonal leaf or flower. When sitting down to such a meal, the diner’s eyes feast only briefly before the dish is eaten, leaving only the memory of what the dish looked like and the sensory satisfaction of having consumed it.

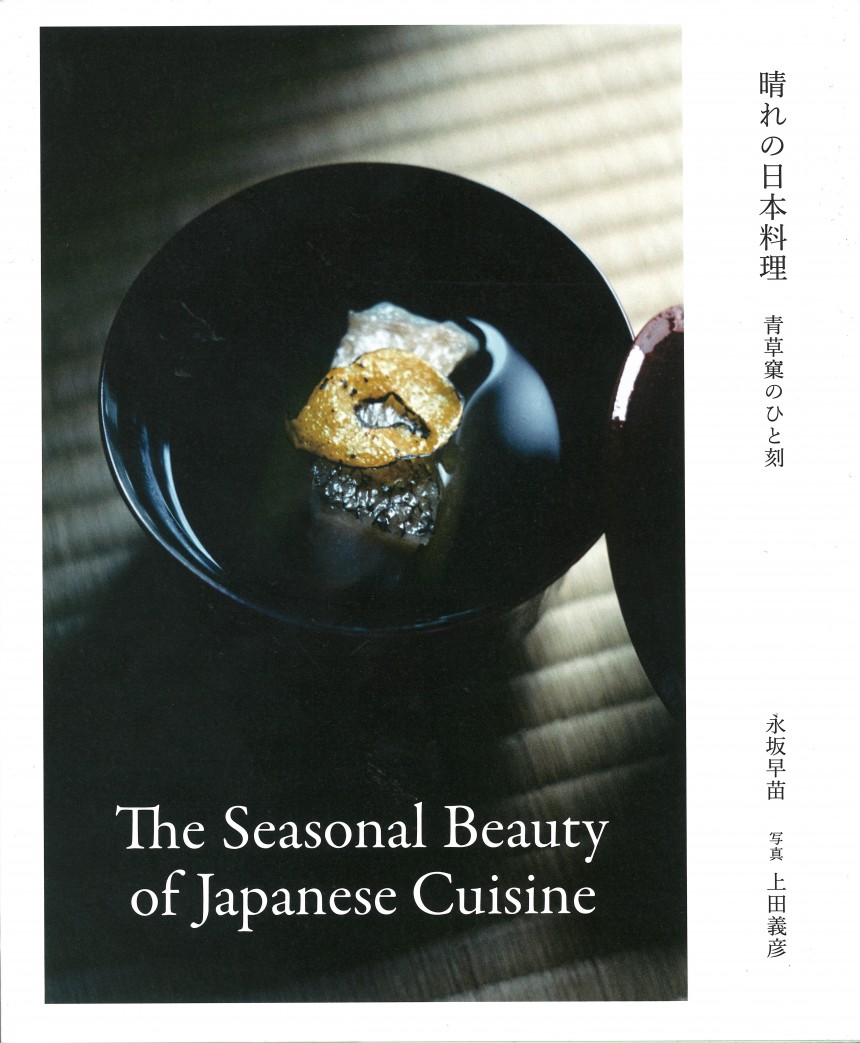

Sanae Nagasaka’s bilingual book, containing incredible photographs by Yoshihiko Ueda, gives readers a more permanent reference to the seasonality of Japanese food. More than 120 photographs depict dishes designed for five distinct seasons: New Year’s, Winter, Spring, Summer and Autumn, as well as seasonal room decorations that would be used in a room where such food is served. For me, the opportunity to study these pictures helped both understand and appreciate which ingredients are best served in which seasons. Perhaps this will enable me to better anticipate the seasons, as well.

In keeping with the sense that these are traditional dishes, they are all photographed sitting on tatami with natural (ie, low) light. The result is truly a feast for the eyes.

Each photo is accompanied by a bilingual description of both the food and the dish on which is presented, or, in the case of the other decorations, many of which seem to be museum pieces or temple treasures, the provenance of the item. For some photographs, there is also an accompanying literary quote, some from Japan’s earliest novels, others from traditional poems written by emperors or other historical figures. Sadly, in a way, these poems are lost on English language readers, as they appear with the photograph only in Japanese. (There is a transliteration, translation and brief explanation for each at the back of the book; such placement is not particularly user-friendly.)

At the end of the book is a short essay by the author as well as some thoughts from the photographer on his experience shooting the photos, but this is predominantly a book of photographs.

The bilinguality of this book make both the book and Japanese cuisine more accessible to foodies who do not read Japanese. Alas, the book is bound in the traditional Japanese manner, on the right-hand side, so that a native English speaker may feel, when handling the book, that it is “back to front”. Of course, someone who can appreciate Japanese cuisine may not find such a small matter particularly off putting.