April 13, 2018

Christianity in Contemporary Japan

Subversion, spirituality and social justice

A radical Jesus may seem out of reach to those who have grown up where the Church is part of the structure of power but, as a minority religion in Japan, Christianity wears a different face.

“Do justice and righteousness, and deliver from the hand of the oppressor him who has been robbed. And do no wrong or violence to the resident alien, the fatherless, and the widow, nor shed innocent blood in this place.”

(Jeremiah 22:3)

I’ve long nursed a view that many “resident aliens” in Japan are running from what our own cultures have done to us. Sadly, for many, the Church has been complicit in the abuse suffered. The narrative of Christianity as subversive religion may seem unfamiliar, and yet that is the reality that the 1% of Japanese people who identify as Christian proudly live each day. As with any religion anywhere, the Church in Japan is not without blood on its hands. Nevertheless, I was impressed and moved by the stories I heard of Christianity in Japan and the strength of the Christians I spoke to.

Is it difficult to be a Japanese Christian in 2018?

Scholar and Japanologist Kittredge Cherry perfectly summarized the contradictions of a Western viewpoint on Japanese Christianity: ‘‘When I was growing up in Iowa, most people went to church to gain social status by fitting in with the dominant culture. But Japan is only about one percent Christian, so Japanese Christians are choosing to ignore or even resist the majority.” Persecution against followers of the minority faith has a long and bloody history. Tens of thousands of Japanese Christians were murdered, sometimes by horrific torture, by the authorities after the Tokugawa Shogunate banned Christianity in the early 1600s. Today Japanese Christians may not face violent persecution but their position can be an uncomfortable one. “There is still strong social pressure from family and friends not to be different. Occasionally you still hear about Christians who have trouble with their family because of their faith, or Christians who lose their job,” Ralph Clatworthy, an American pastor working in Japan, tells me. “This is not an easy thing to teach to Japanese believers, but we pastors need to make sure believers understand that this kind of experience may be a part of their life of faith, even today.”

Amongst the Japanese Christians I spoke to, whilst most had not faced outright discrimination, many suffer frequent microaggressions. “I’ve certainly met Japanese people who are utterly uncomfortable with just the thought of someone having a shukyo (religion). In their minds there doesn’t seem to be a distinction between mainline religions and money-sucking cults that deceive people and destroy lives,” says Yuko, a Japanese Christian in her 40s who worships at Tokyo Union Church. “They’re also uncomfortable with me not believing in or partaking in uranai (fortune telling) or Shinto/Buddhist rituals … I know some of them think I am very intolerant for not conforming.” Another member of the TUC congregation who did not wish to be named, cited an additional concern: the death arrangements of Japanese Christians. “Most graves are family graves situated in the back yards of temples. If you are a Christian, you have to have your own grave outside the temple as the temple may not permit Christians.”

Difficulties notwithstanding, my interviewees told me how their faith was a huge source of joy and pride in their lives. Many said that contributing to the community was an important part of being a Japanese Christian. Yuko didn’t convert until she was 21 but traces her interest in Christianity back to her childhood. ‘‘I developed a very positive view of Christians in Japan (both Catholic and Protestant) as people who were actively engaged in social welfare and social justice work in my country, so I think I was always drawn to the social action part of Christianity. I think Christians in Japan have made a lot of contributions to Japanese society, even if the number of followers has not increased. So many hospitals and schools and social welfare organizations were/are built and run by Christian missionaries and Japanese Christians.” Rio, another Japanese member of the TUC congregation, agrees, “Sometimes, too much analysis on the situation of Christianity in this country can distract (myself included) from working on our own character. But exactly that is key to winning over others, is what I feel.”

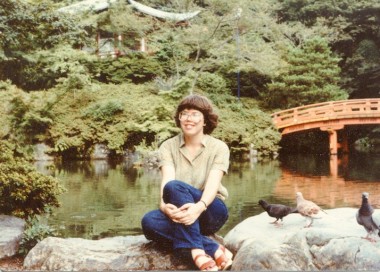

Outcasts and lepers: On the “subversive” religion

Kittredge Cherry has been a devout Christian since a religious experience in Kobe in the 1980s. Now living in California, she is best known as the author of Womansword: What Japanese Words Say About Women, a fascinating dissection of gender and language in Japan. Cherry is a feminist, lesbian and a Christian: I asked her what it was like to live with that triple whammy of “otherness” during her years in Japan. “Being a foreigner in Japan trumped everything else by far,” she recounts. “That made it easy to live in Japan as an American lesbian feminist. Japanese expect foreigners to be barbarians who break rules.”

For Cherry, her sexuality and faith were never incompatible, “As soon as I connected with God, I knew without a doubt that God loved all of me, including my sexuality.” She cites her baptism in Kobe as an example of how queer sexuality and Christianity came together in her life, “My baptism ceremony was almost like a same-sex wedding. The church required me to have a sponsor stand beside me and promise to guide me in faith, so I chose Audrey Lockwood. Nobody else knew at that time that we were lovers, although many suspected. Audrey and I stood side by side as the pastor gave a blessing. She is still the love of my life and we were finally able to marry legally in 2016 – more than 30 years later.” Cherry is unapologetic and joyful in her own convictions but she is not naïve, admitting that some homophobia was sadly imported to Japan by over-zealous missionaries. “Being an LGBTQ Christian is doubly hard because we are rejected as radical heretics by many Christians, but ostracized as fossils and sell-outs by much of the secular LGBTQ community.” For LGBTQ Christians based in Tokyo, Shinjuku Community Church (lead by gay pastor Yoshiki Nakamura) and LGBTQ Catholics Japan are Cherry’s recommended places to worship.

I must confess, when I read Cherry’s Womansword I was surprised to discover that the staunchly feminist author, fearlessly dissecting the Japanese terms for adultery, sex education and cross-dressing among other things, was an ordained priest. “To me it’s natural for Christianity and feminism to go together,” says Cherry. “Even before I became a Christian, I was attending International Feminists of Japan meetings in the basement of Tokyo Union Church. When I joined the church, I heard sermons about how Jesus dared to love outcasts, including women, lepers and foreigners. I heard Bible readings such as, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” (Galatians 3:28).”

Western journalists have cited the “failure” of missionaries to convert Japan to Christianity but when I look at this 1%, joyfully practicing their faith and serving their community, I don’t see failure. Ironically, perhaps it is because Christianity is a minority religion that these quiet radicals are able to carry out the “come not to be served but to serve others” aspect of their mission so successfully in Japan. When I ask Yuko about her hopes for the future of Japanese Christianity, she is not concerned with numbers but with good works. “I just hope people from all over the world who are now in Japan, who may have been hurt by Christianity in the past where perhaps Christianity is part of the establishment and the power structure or where the churches are complicit in oppression, would find the tiny minority of Christians in Japan refreshing, as we struggle in our small ways to practice our faith by serving others.”