June 13, 2023

Fresh Ink: Debut English Translations of Chuya Nakahara’s Japanese Literature

The English-language debut of a Japanese modernist master

…This world is like the sea.

I thought of the restless sea in the evening

There, a boatman with a weathered face

While working his oar with faltering hands

Wondering if there might be any catch

While staring at the surface, passed on by

In this excerpt from “Exhaustion”, Chuya Nakahara declares that we are all buried in the depths of rolling waves, a tumultuous tomb. Whole lives of suffering and joy lay just out of sight in the murky waters, all the while others pass on by, glimpsing us with their own selfish purposes.

Perhaps this poem can help us understand Nakahara’s poetry in a way: Nakahara is the boatman, and the world is the sea. Or we are the boatmen, and Nakahara is the sea.

Chuya Nakahara’s melodic and puzzling poems are well-known in Japan. Musicians have turned his haunting refrains into songs; generations of writers and artists have kept his poems close to their chests. And while he was little known during his lifetime, scholars recognize him as among the greatest of Japan’s modernist poets. A bilingual edition of the first of his two poetry compilations, Poems of the Goat, is now available from Bright Wave Media with translations by Ry Beville.

These translations pay meticulous detail to capturing Nakahara’s startling images, melodic meter, and poetic message that still resonates today: one of deep wounds and suffering, but a love for life, nature, and the world that somehow manages to outweigh all of the pain.

“Chuya is both challenging and accessible,” Beville writes. “His work is furthermore deeply personal. He writes about love and its difficulties, his relationships with others, and emotions whose origins or reasons the speaker seems at a loss to place.”

“Though Poems of the Goat made little more than a ripple in the literary world on its initial publication, it hardly seems like a modest start to a poetic legacy now. This was a powerful debut.”

Nakahara was born in 1907 in Yamaguchi. Interested in literature from an early age, he published poems in local newspapers as a child. He moved to Tokyo in his youth and made friends and mentors among notable literary figures, like Hideo Kobayashi, Shinkichi Takahashi, and Tetsutaro Kawakami, and became known as “Mr. Dada” for his love of Dadaist poetry. He increasingly joined literary activities as he researched French poetry and Symbolism, a poetic movement that favored abstract representations through sensory, esoteric, and metaphorical images.

It took Nakahara a long while to achieve any degree of success—after years of struggling, a publisher finally agreed to publish Poems of the Goat in 1934. But he died just three years later of tubercular meningitis. In death, he left behind one last completed manuscript to Kobayashi, Poems of Days Past.

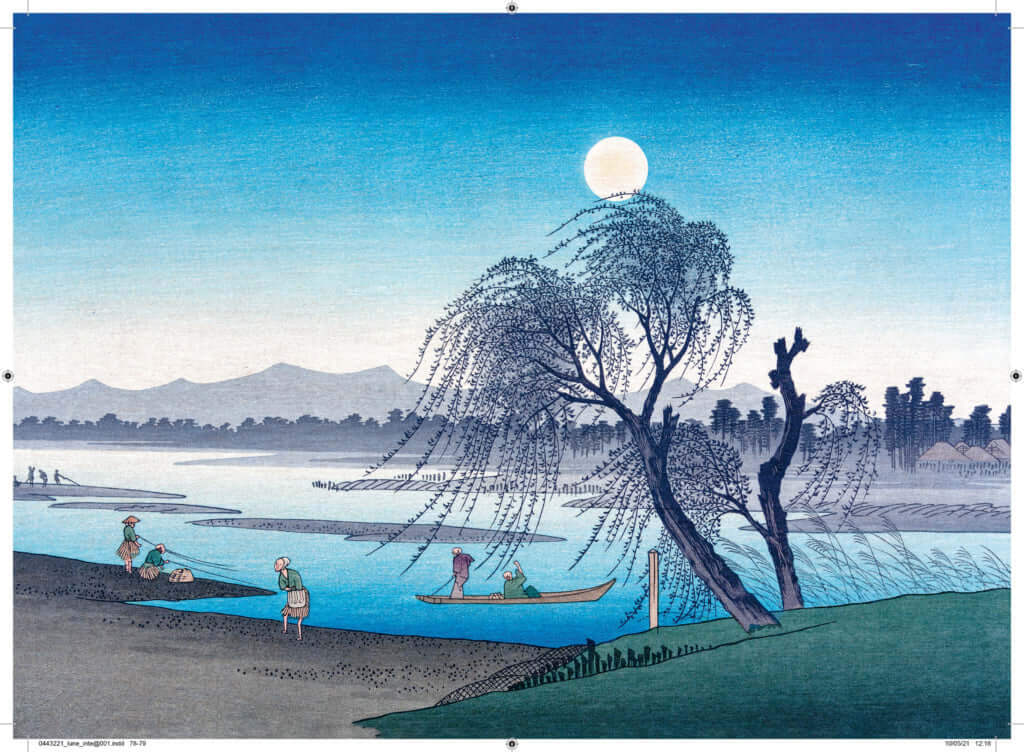

With all of its puzzling and yet evocative images, Poems of the Goat is clearly a work of symbolist poetry. Many of the poems feel cryptic. Nakahara uses creative language and turns of phrases, inventing bizarre but vivid, animated images. Take these excerpts from “The Moon,” one of the first poems in the collection:

Tonight the moon goes sadder by degrees,

Eyes wide, astonished at a foster father’s distrust.

Time washes a silver wave across the desert

And the earlobe of the old man glows fluorescent.

O—the forgotten banks of the canal

The rumble of tanks lingering in one’s chest

With a cigarette drawn from a rusty can

The moon is smoking listlessly.

“Sometimes Chuya is simply weaving together images and phrases to engender sensations or emotions in the readers that he also felt at the time of inspiration,” Beville explains. “What is meaningful floats just beyond language.”

Poems of the Goat is also a work of lyricism, with a careful focus on form and meter. Nakahara typically uses ‘syllabic’ units of 5 and 7, standard meter in Japanese poetry, but deviates occasionally into units of 6 and 8 to achieve a songlike quality. His use of repetition and refrain make his poems all the more singsong. As a result, some of the poems are easy to remember, no matter how cryptic they are. A good example is what Beville describes as probably Nakahara’s most famous poem, “In All This Sadness Sullied Deep”:

In all this sadness sullied deep

The snow descends again today

In all this sadness sullied deep

The wind intrudes again today…

In all this sadness sullied deep

Profound with pity, fear abides

In all this sadness sullied deep

Bereft of choices, the day darkens

But Poems of the Goat is also a personal reflection and declaration. The poems at the beginning are primarily imagistic observations of the world, burying mysterious stories and pain under lush, emotive descriptions of scenery and the seasons. But they evolve. Bit by bit, the personhood of Chuya Nakahara emerges: he starts to tell stories of his childhood, his loves, his suffering. Poems of the Goat concludes on several confessional poems that stir and astonish with their angst. A reader confronts Nakahara’s pain, and his motivation to stir us with his language and art, in “Exhaustion”:

My idleness weighing in the sag of my arms

The sun shines today as well yes, the sky is blue

Perhaps since long ago

All I ever controlled was this idleness

The earnest hope as well within that idleness

Was all that ever awed me

O but even then, but even then,

I never thought I’d become that man who only dreams!

Even with Beville’s introduction and description of Nakahara’s techniques, these poems can be difficult to penetrate. I needed to immerse myself in his words for some time before I started to enjoy the work. Eventually, I accepted the inventive but bewildering terms of phrase on their own terms and heard the music in his verses.

Beville’s translation is rigorous in its use of English poetic meter (such as using iambic tetrameter or pentameter, typically found in sonnets) to render an equivalent sense of musicality and formality. This lyricism keeps Nakahara just accessible enough to be enjoyed—but there are deep depths to be plumbed. The translation demonstrates why Nakahara has endured as a beloved figure, and several of the English translations are worthy artistic objects in their own right.

“I first read him in the 1990s, just out of college, and was impressed by his rhythms and the worldliness of his poems,” Beville says. “As I’ve gotten older, I find that I relate in different ways to his poetry and appreciate different poems, especially those about his child (I have two kids now), or simply accepting that you have to get on with life, despite its setbacks and disappointments.”

Observations of sublime beauty, reflections on war and history in an autumn landscape, and pleas to hear and be heard—Poems of the Goat is a remarkable volume of poetry that contains all of this and more. At times stiff, at times dazzling. But the concluding “The Call of Fate” sums up Nakahara’s project, and arguably, the project of poetry and art:

In other words, it’s a problem of passion.

You—if from the depths of your heart are furious,

Then rage away!