November 16, 2023

Food in Japanese Film and Fiction

The hidden protagonist in films and literature

By Trevor Kew

Anyone who has ever turned on a television in Japan knows that food dominates the conversation here like nowhere else in the world. Seemingly every other channel has something delicious filling the screen. But the significance of food in this country runs far deeper than news anchors sampling Aomori apples or comedians in watermelon helmets searching for tonkatsu restaurants. Like so many other cultures, food is the omnipresent element of Japanese life, meant not merely to be consumed but savored, discussed and shared.

Maybe that’s why so many of Japan’s finest writers and filmmakers have made food a part of their work. What better metaphor is there for the range of experiences across Japanese society?

Banana Yoshimoto’s novel Kitchen uses food to explore loneliness and disconnection in modern urban Japan. It portrays a young woman named Mikage struggling with loss who gradually, through the simple pleasures of preparing and sharing meals, begins to rebuild her shattered life. For Mikage, a kitchen becomes far more than just a room in a house. “I often think that when it comes time to die, I want to breathe my last in a kitchen,” she says. “Whether it’s cold and I’m all alone, or somebody’s there and it’s warm, I’ll stare death fearlessly in the eye. If it’s a kitchen, I’ll think, ‘How good.’”

Yaro Abe adopts a more communal approach in his manga Midnight Diner (Shinya Shokudo). The stories take place in a small late-night eatery that attracts an unusual range of customers (housewives, salarymen, gangsters, strippers) who gather around a single counter, giving brief glimpses into the triumphs and tragedies of different Tokyo lives. The Master, a man of few words, responds to his customers only with his pots and pans. The manga is not yet available in English, but a television adaptation (with English subtitles) has gained a worldwide following on Netflix.

Japanese films that focus on family dynamics often revolve around dinner tables. In Yasujiro Ozu’s An Autumn Afternoon (1962), a widowed World War II veteran spends his evenings eating and drinking with men his age rather than his family. While he wants the best for his daughter and son, he struggles to relate to the post-war generation. The film’s Japanese title, A Taste of Sanma, refers to the delicious needle-nosed fish that symbolizes fall in Japan, a subtle nod to the clash between tradition and inevitable change. In Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Our Little Sister (2015), three sisters from a broken marriage decide to adopt their teenage half-sister. As wrongs and resentments from the past seep in, the little table where they kneel together over home-cooked meals seems like all that holds them together, along with the umeshu (plum liquor) that they brew using fruit from their grandmother’s tree.

Not that sharing (or obtaining) food is always easy. The family (of sorts) in Kore-eda’s Shoplifters (2018) survives by stealing packaged food and gobbling it greedily on the floor of their rundown home. We soon learn that they view one another much like the food that they steal, as little more than a means to get by. Such distrust amidst deprivation also permeates the horror film Onibaba (1964). Set in Japan’s turbulent Sengoku period, it portrays an old woman and her daughter-in-law who lure warriors into a pit before murdering them to steal their armor and sell it for rice. They eventually turn on one another, driven by jealousy for the man who purchases their stolen wares.

Beyond the urban and domestic, food in Japanese film and fiction connects us to the remote places of the country as well. Yukio Mishima’s novel The Sound of Waves devotes an entire chapter to a small island’s ama-san, female free divers who plunge to great depths to gather seafood. The award-winning manga series Golden Kamuy (available in English) whisks us off to the frontiers of early 20th-century Hokkaido, delving deep into the language and culture of Hokkaido’s indigenous Ainu people, particularly their hunting, fishing and unique cuisine. Natsume Soseki’s classic novel Botchan follows a cocky young man from Tokyo on his first teaching assignment to rural Shikoku. Homesick, he gulps down four consecutive bowls of “Tokyo-style” tempura soba noodles at a restaurant, only to discover “Professor Tempura” written on the blackboard when he arrives at work the next day.

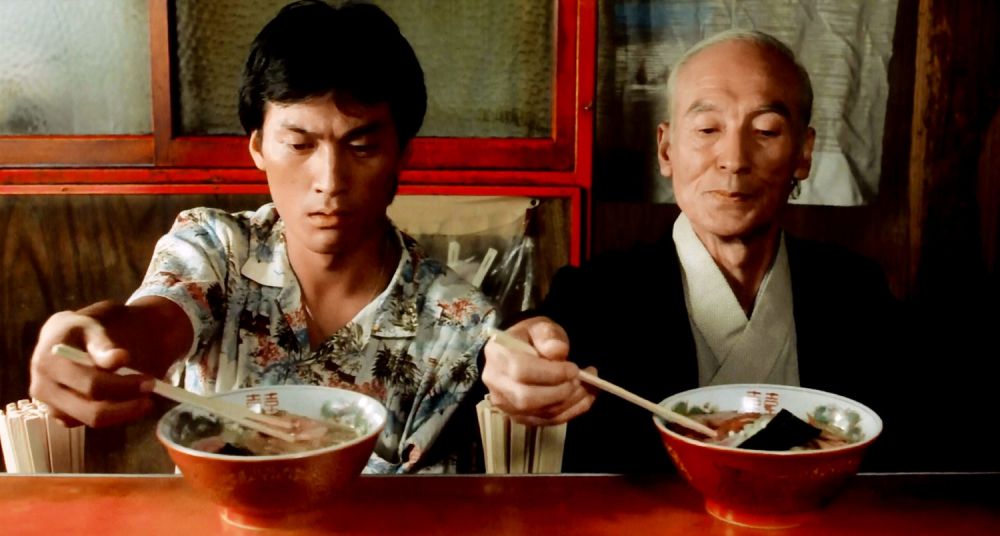

Food is also an endless source of creativity and humor in Japanese film and fiction. Haruki Murakami’s short story The Second Bakery Attack follows a pair of newlyweds who arm themselves one night to head out and rob a bakery (again…). The bakeries are all closed, so they decide to rob a fast food restaurant. “It’s like a bakery,” claims the wife. “Sometimes you have to compromise.” The “noodle Western” Tampopo (1985) features a decrepit ramen shop brought back to life by an unlikely outlandish cast of characters (including a young Ken Watanabe). And the wonderful children’s picture book Dosukoi Sushizumo gathers different varieties of sushi to face off in a series of hotly contested sumo bouts (while not yet available in English, the artwork is remarkable and if you know hiragana, it’s easy enough to read).

Perhaps, in the end, it’s no surprise that Japan devotes so much print and screen time to food. What is so impressive about the best works of Japanese film and fiction is how they connect food to so much else.