August 12, 2021

So You Thought You Didn’t Like Manga?

A dive into the English-language side of Japan’s alternative manga world

Do you think manga is all blustering fantasy action or slow-burn high school romance? Think again. Alternative manga has a long, storied history with experimental art forms, sophisticated literary conceits, adult themes. And it’s starting to emerge more prominently in English translation.

While the manga that most readers are familiar with has fantastic storytelling and beautiful art, alternative manga engages in exciting, unique and even abstract styles. And nowadays, more mainstream and small publishers in the U.S. and UK are starting to pursue experimental, sophisticated manga for translation and publication in the U.S., based on a veritable treasure trove of old material — and a continuing contemporary pipeline of exciting literary comics.

“I think interest in the west shifted in the 2000s with the release of Drifting Life by Yoshihiro Tatsumi,” says Ryan Holmberg, a translator and historian focusing on literary and alternative manga. “Tatsumi was historically important in Japan in the 1960s, and his biography became a huge hit in the States. That came on the wave of so-called literary graphic novels becoming big in the English language publishing world in the early 2000s.”

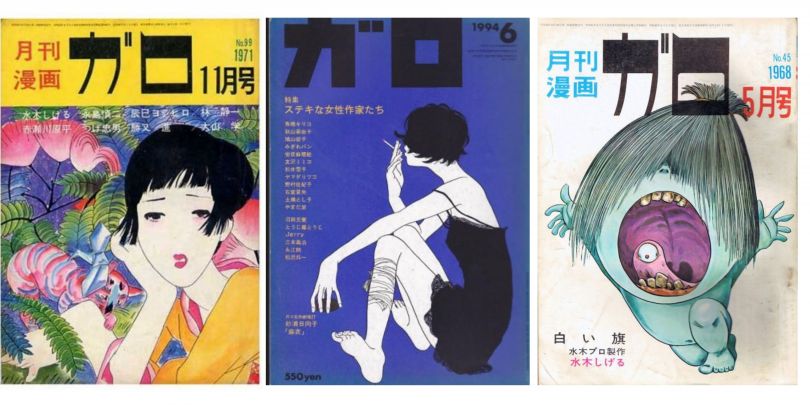

Even today, the alternative manga world in some ways rides on the coattails of the explosive 60s and 70s. At the center of the movement was the magazine Garo, a publication that became the centerpiece of leftist student movements in the late 60s and 70s, and which expanded manga into unexplored realms.

Per Liu Xing of Leap Magazine, Garo’s main readership was leftist students influenced by avant-garde art who were willing to accept anything that broke away from traditional tastes. “Garo was able to veer from common perceptions of beauty and entertain alternative tastes,” writes Xing. One of the first artists that shocked and captivated this generation of leftist students, Yoshiharu Tsuge, has only recently emerged in English translation despite his status as a bestseller and legend in Japan.

One of Tsuge’s masterpieces, A Man Without Talent, was just published in English earlier this year, and is a great introduction into the world of literary manga. “Part of The Man Without Talent’s success is that it fits so well into the market and genre of literary graphic novel in the U.S,” explains Holmberg, the translator of the work. Man Without Talent is about the daily life, meditations and human interactions of Tsuge’s cartoon stand-in, Sukezo Sukegawa, as he attempts to support his family through selling stones, fixing up broken cameras and any other endeavor that seems destined to fail. It is a thoughtful work enveloped in the authenticity and crudeness of its self-centered protagonist, while the art captures images, stories and mythologies with beauty and sensitivity shifting smoothly from background to foreground and back again.

In the Japanese market, literary and alternative manga aren’t ‘separate’ from other manga. Japan’s wider diversity of manga genres spills over into the experimental. While the contemporary experimental manga world is far from what it was in the 60s and 70s, the scene continues to thrive.

“Small arthouse galleries and bookstores that mix exhibition/retail and publishing activities, independent manga magazines and a self-publishing culture help to foster and simplify artists’ self-publishing activities and make it easier to follow interesting new works and artists,” says Emuh Ruh at Glacier Bay Books, an Oregon-based publisher of alternative manga. “Tracing this back, we try to follow interesting artistic comic work and look at connecting with people working in this area.” Seirin Kogeisha’s Web Reads and the independent zine scene found in stylish retail spaces like Taco Shop are just a few rich sources of new alternative manga getting released in Japan.

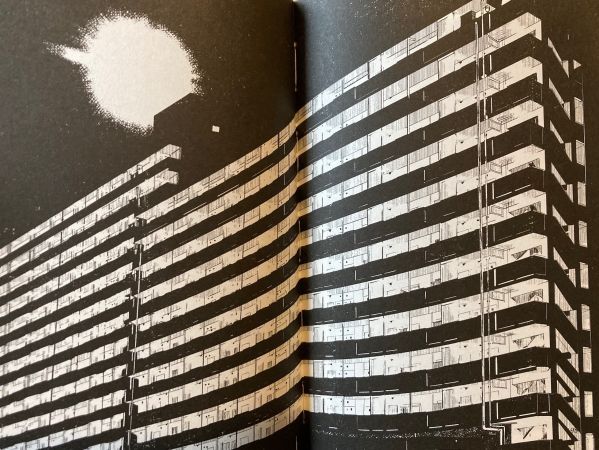

In recent years, more English-language publishers have started to explore this world. Glacier Bay Books is one of those publishers, with exciting titles such as their newest, Children of Mu Town, a classic yakuza crime manga that intermingles themes of gentrification and rebirth. The story focuses on children in an aging residential housing complex who are struggling to survive. The art is more standard than some of the art seen in a work like Man Without Talent, but the story carries impressive weight.

“Children of Mu Town has been lauded for its contemporary socio-political commentary as well as its awe-inspiring inky depictions of a city’s night visage, its tenements and neighborhoods; the lost dreams of a generation resting in its bones,” says Ruh.

“I’m interested in expanding the infrastructure of different publishers out there,” says Holmberg. “Some of this artsy manga won’t sell that much, so it’s good to have smaller publishers in the mix.”

The emerging audience for these works comes together due to a variety of factors. The broader manga market has exploded in recent years and continues to grow at a remarkable pace. While this growth is driven largely by popular action and fantasy titles, insiders agree that broader industry growth has some trickle-down effect on more experimental comics. Other new readers are manga fans entering new arenas or long-time fans of Western graphic novels, checking out manga as Japanese culture continues to win new fans abroad. (Japanese literary fiction has also made strides in recent years, with a diverse set of writers earning broad critical and commercial success.)

“Our titles have had a strong appeal among readers that run in both manga and ‘indie comics’ circles,” says Ruh. “We’re seeing a growth of interest in more unusual and artistic works as new readers from different backgrounds become aware of these kinds of works, and continuing readers begin to look for more variety.”

While the common perception of manga is as genre fiction, the world of literary manga has a serious pull and punch. Drawn & Quarterly, Glacier Bay Books, Breakdown Press in London, and others have a wide variety of offerings for interested readers, and their horizons are expanding.

While literary manga has historically been a masculine world, Holmberg says that the publishing industry is making an effort to redress the balance by bringing in more female artists.

The Sky is Blue With A Single Cloud by Kuniko Tsurita, translated by Holmberg, is one of these titles, with Tsurita lauded as a “formally ambitious and poetic female voice like none other.”

“I’m very optimistic for the future of literary manga,” says Ruh. “I think it’s fair to say that members of this new wave are broadly premised on the idea that the current situation in publishing has not reflected the true diversity of both comic creation, nor readers’ interest.”

Thanks to new translations and publication efforts, English-language readers are able to find a wide variety of artistically brilliant and philosophically deep manga. The common perception of manga as pulp fiction deserves serious reconsideration in the English language.

More stories about manga and literature:

One of the most anticipated Japanese novels of 2021

‘My Pointless Struggle’ by Yohei Kitazato

The secret to success in Japan’s cut-throat business world? Being as selfish as possible

Why the World Needs Literature

Conversations with award-winning author Yu Miri and translator Morgan Giles