February 26, 2009

Going Native

Tokyo's thriving Ainu community keeps traditional culture alive

By Metropolis

Mina Sakai's great-great-grandfather Amaytaki with a fresh kill Courtesy of Mina Sakai

In September 2007, the UN General Assembly passed the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, prompting the government, which feared international criticism ahead of the G-8 summit in Hokkaido last July, to pass a resolution recognizing the Ainu as an indigenous people of Japan.

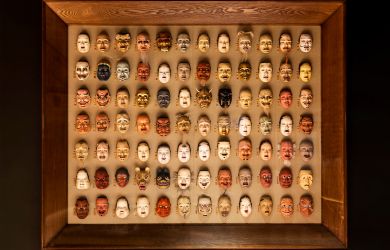

Photo by Andy Sharp

To coincide with the gathering of political leaders, Sakai helped organize the Indigenous Peoples’ Summit in Ainu Mosir 2008, an event attended by aborigines from around the world. In addition to celebrating traditional culture with music and dance, the proceedings had a serious side. Participants demanded the government grant the Ainu rights of self-determination and control over natural resources. They also called for educational improvements, including the adoption of the Ainu tongue as an official language of Japan and the creation of history textbooks from Ainu perspectives. Most significantly, they demanded a formal apology for past wrongs.

But is the message getting across to the politicians in Nagatacho?

Hiroshi Imazu is a lower house lawmaker from the ruling Liberal Democratic Party who led a bipartisan group to draft the resolution recognizing the Ainu. Yet despite his pro-aborigine stance, he rejects out of hand the notion of an apology.

“Japan’s situation is different to that of Australia or America,” Imazu told Metropolis in an interview at his Diet office. “I don’t think an apology is necessary and I think the Diet resolution is enough to show our feelings [toward the Ainu people].”

Ainu culture lives most vibrantly through its music and dance. Epic yukar deity songs are performed at religious ceremonies and have been passed down from generation to generation. Unique Ainu musical instruments include the tonkori, a zither with five strings made from a species of nettle, or whale, deer or reindeer tendons, and the mukkuri, a type of Jew’s harp. Ainu dance can be playful or spiritual, and is usually only performed by women.

Sakai and her brother helped found the Ainu Rebels in the summer of 2006 to have some fun studying their native culture, but the band evolved into a performance group fusing traditional song and dance with rock and hip-hop.

While some elders disapprove of the Rebels, accusing them of debasing traditional culture, most are supportive, seeing, as Sakai does, how they are not just keeping the culture alive, but taking it to a new audience.

“It’d be a bit dull if it was just traditional music, but we get through to young people by playing club events,” she says.

Other well-known Ainu artists include Oki, a tonkori player who leads the psychedic-tinged Dub Ainu Band, and the Ainu Art Project, a network of dancers, singers and storytellers that was a precursor to the Ainu Rebels.

The Rebels themselves have until now concentrated on live shows, but a CD is in the pipeline for release later this year. Almost all of their songs are in Ainu, with Japanese only used to rap their message home.

The Ainu Rebels in action Courtesy of Mina Sakai

“Make an Ainu movie for us! Please document our voices for future generations!”

This plea from Shizue Ukaji, a huci, or female Ainu elder, got the reels spinning for Tokyo Ainu, a documentary set for release in early 2010. The movie is directed by Hiroshi Moriya, a former TBS documentary maker who has produced films on indigenous peoples in such far-flung locales as Siberia and the Amazon. Made without narration, the film lets the vivacious Ainu of Tokyo tell of their own travails and aspirations. English subtitles are planned in the hope that the movie might generate interest on the overseas film festival circuit.

A highlight of the film is the Charanke Matsuri, a celebration of Okinawan and Ainu music, dance and culture held every November in Nakano. The festival is organized by the Ainu Utari Renraku-kai, one of several Ainu communities in Tokyo, a group centered on the Rera Cise restaurant.

Maoki Sato, head of the film’s production committee, hopes the movie will increase awareness among Wajin that Ainu are living among them. He also points to a lost way of life.

“Ainu have a different culture and civilization to Wajin,” Sato told Metropolis. “They get what they need from nature and share it among the community, giving to the old and needy.”

The undoubted star of the film, however, is an Ainu elder whose only need is to preserve the traditions of his people in these modern times.

Haruzo Urakawa(left)

Photo by Andy Sharp

Haruzo Urakawa, 70, is a bull of a man who has worked the fields since he was out of diapers. Brought up on a Hokkaido farm, Urakawa, the younger brother of Ukaji, has held, among other roles, the chairmanship of the Kanto Utari Association. Such is his status in the Ainu community that the film was originally going to be titled Haruzo, an Ainu.

The assiduous Urakawa has singlehandedly constructed three cise—traditional Ainu homes with thatched roofs—in the Kanto region. He leveled the land to build his third such home, dubbed Kamuy Mintara (“Playground of the Gods”), as a venue for Ainu cultural exchange in Kimitsu, Chiba Prefecture.

Kamuy Mintara is a place of peace, bedecked with deerskin rugs, wooden effigies of bears, salmon-skin shoes, inau prayer wands, and mounted deer and pheasant—all symbolizing the Ainu’s sustainable, spiritually focused coexistence with nature.

“So much could be lost if I didn’t do what I’m doing,” Urakawa says. “I hope that people will come to stay at Kamuy Mintara to help out with the facility and the land.”

With his long wispy beard and hands as big as a bear’s paws, Urakawa, who still wrestles in sumo tournaments, could almost be the bear god that stands guard out front.

This doyen of the Ainu people stubbornly refuses to fit into a society in which he sees much wrong. Like Sakai, he too is a bit of a rebel.

Mina Sakai Leading Ainu musician and activist. www.ainupride.com

Ainu Rebels Local musical ensemble, often performs around Tokyo. www.ainurebels.com

Ainu Culture Center A repository of Ainu history and artifacts. 2-4-13 Yaesu, Chuo-ku. Tel: 03-3245-9831. Open Tue-Fri, 1-9pm (entrance by 8pm); Sat and Hols, 10am-6pm; closed Sun,-Mon & holiday eves. Nearest stn: Tokyo, Yaesu south exit. www.frpac.or.jp

Ainu Association of Hokkaido Information clearinghouse and advocacy organization. www.ainu-assn.or.jp

Tokyo Ainu Documentary focusing on the local Ainu scene, set for release next year. www.kamuymintara.com/film/eng/top.htm

Kamuy Mintara Haruzo Urakawa’s living museum in Chiba. Open by appointment. 3-1 Okinodai, Kiwadahata, Kimitsu-shi. www.kamuymintara.com. For information in English, e-mail Mika Narukawa at mintara2004@yahoo.co.jp.

Rera Cise restaurant www2.odn.ne.jp/rera