January 15, 2018

Ikebukuro’s Bohemian Ghosts

The former art colonies of Northwestern Tokyo.

By Clark Parker

Mejiro & Ochiai

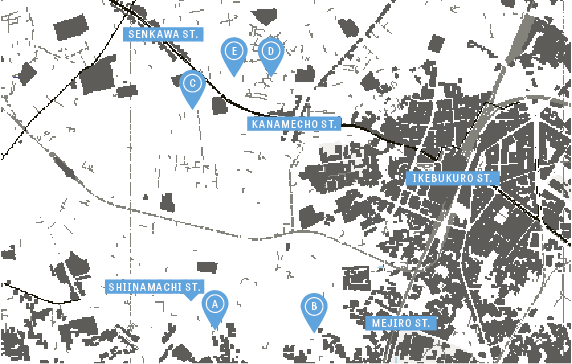

The Yamanote Line, used correctly, is a reasonable approximation of a time machine. Get off at the wrong station — Shinjuku, for example — and it may not work. But alight at, say, Mejiro, and you can visit previous decades with relative ease. Mejiro Station, located at the edge of the Ochiai and Mejiro districts, is a wonderful place to experience the past. Here, quiet residential streets fan out to the west of the station, embellished with pockets of natural beauty such as Mejiro Teien and Otome-yama Park. Ochiai and Mejiro retain an air of quiet affluence that has been cultivated for nearly a century and is exemplified by Tokugawa Village, a semi-gated enclave built in 1969, that attracts foreign residents. But the heart of this area was formed in 1922 with the birth of Mejiro Bunkamura, a series of “cultural villages” for the rich and/or Western-minded; residents included the openly gay writer Nobuko Yoshiya (1896 – 1973) (the first Japanese woman to own a racehorse) and Tanzan Ishibashi (1884 – 1973) a journalist-turned-politician who would serve as Prime Minister in the 1950s.

The Bunkamura caught the attention of artists and cultural observers for the style of its homes and for the behavior of its residents; a cartoon by Ippei Okamoto (father of famous artist Taro Okamoto) poked fun at the indolent rich by depicting farmers at work in the foreground and golfers at play in the background. The Bunkamura also made an appearance in a story by the great mystery writer Edogawa Ranpo (1894 – 1965). In his tale “The Red Room” (1925), Ranpo describes a “suburban cultural village” and its seiyoukan (Western-style houses). Ranpo being Ranpo, the quiet streets bear witness to a gruesome crime in which a schoolboy is tricked into urinating on an electrified wire, thereby electrocuting the boy. Ranpo’s pen name was modeled after the Japanese pronunciation of Edgar Allan Poe (Edogā Aran Pō). His writing studio and library, near Ikebukuro Station, is a two-story storehouse that survived the WW II firebombing of Tokyo. And his stories contain bizarre and grotesque flourishes capable of making even today’s readers squirm.

Many of the original Bunkamura houses were destroyed during the war, and two large roads were added, but the overall street pattern remains intact. And if you look closely, you can still find some of the original structures. More easily, you can visit the Yuzo Saeki Atelier Memorial Museum, the restored studio of the youga (Western-style) painter who captured the essence of the Ochiai area in over fifty works from the 1920’s. Saeki’s paintings of the Bunkamura include “Tennis,” “Shimo-Ochiai Landscape” and “Ski Hill.” Saeki, while living in Paris, died from tuberculosis in 1928 at age 30.

Closer to Mejiro Station is the Tsune Nakamura Atelier Museum, the former studio of another youga painter from the same era. Nakamura’s atelier is a beautiful, compact building with large, north-facing windows, a clapboard exterior and upturned finials at the edge of the roof, reminiscent of Thai architecture. The interior recreates the studio as Nakamura may have used it. Nakamura worked here from 1916 until his death in 1924 at age 37 (also from tuberculosis). After visiting Nakamura’s studio, I suggest having lunch at the friendly café hiroma, which serves a nice yakuzen curry.

The Kanamecho, Nagasaki and Chihaya districts of Toshima-ku

Having just immersed ourselves in art and architecture from the 1920s, we continue north to an area where a thriving arts movement would flourish in the 1930s. North of the Seibu-Ikebukuro Line we leave Mejiro and enter the Nagasaki district of Toshima-ku. Nagasaki and the neighboring Chihaya and Kanamecho districts share the same cultural legacy; beginning in 1931, hundreds of artists would move here, drawn by purpose-built rentals with studio space and large windows. Studios were built in clusters and given evocative names such as Sparrow Hill and Sakuragaoka Parthenon. Collectively, these artists’ colonies have become known as Nagasaki atorie-mura (Nagasaki Atelier Village). A more romantic term also emerged: Ikebukuro Montparnasse, named for Ikebukuro, the closest urban hub, and Montparnasse, the bohemian section of Paris that was familiar to many Japanese artists, including our friend Yuzo Saeki. Incidentally, the poet who coined this term, Hideo Oguma, died from tuberculosis at age 39.

In addition to its artists, Nagasaki was known for its countercultural vibe. Oguma’s description of Ikebukuro Montparnasse mentioned Kinema (movie) actors, Catholic priests and buraikan (outlaws), emphasizing the area’s character as outside the boundaries of normal society. The artists were known for their unusual appearances, similar to the long-haired hippies of a later era. As World War II wore on, many artists were deemed Hikokumin (a term that became taboo following the war) for a perceived failure to support their country. According to a possibly apocryphal story, the artists of Nagasaki would hold dance parties during the Allied air raids.

Due largely to the air raids, very few structures from this era exist, and none rival the lovingly restored atelier in Ochiai. Instead, signs and other markers commemorate a handful of the Nagasaki Atelier sites. Tsutsujigaoka (Azelea Hill) is graced by a sculpture by Mine Takashi, and Sakuragaoka Parthenon is honored by a dead tree (also tuberculosis?). The most lasting monument is the museum honoring Morikazu Kumagai (1887 – 1977), built on the site of the painter’s home where he lived from 1932 until his death (surprisingly, not tuberculosis).

In the last segment of this tour we will visit the atelier that started it all. It all began in 1928 when a studio was built for Nara Tsugio by his grandmother. Inspired by this example, other studios were built, and by 1931 Suzumegaoka (Sparrow Hill) had emerged as an atelier village. While the original studios are gone, the neighborhood’s benign maze of curving, sloping roads makes it easy to imagine the artists who lived here.

At the top of the slope, hiding down a stone path, is Cafe Toukasou, a 1954 private residence that was converted to a cafe in 2014. In addition to food and drink, the venue, in the spirit of Ikebukuro Montparnasse, hosts intimate concerts and events. Even if you don’t eat here, you may feel a sense of accomplishment from merely finding this hidden cafe and its lush garden setting. Not hungry? Have a beer or two at Cat & Cask Tavern, just a few minutes’ walk from Cafe Toukasou. It has comfort food, great beer and a cozy neighborhood-pub feel. From here it’s less than a kilometer to Geneijou (“Castle of Illusion”), Ranpo’s former writing studio and part of Rikkyo University’s campus. If you have too much to drink at Cat &Cask, make sure you go to the bathroom before you leave; Ranpo has a special way of dealing with people who don’t relieve themselves properly.

Yuzo Saeki Atelier Memorial Museum (A)

2-4-21 Nakaochiai, Shinjuku-ku

regasu-shinjuku.or.jp

Tsuneishi Nakamura Atelier (B)

Shimo-Ochiai 3-5-7, Shinjuku-ku

regasu-shinjuku.or.jp

Kumagai Morikazu Museum (C)

2-27-6 Chihaya, Toshima-ku

kumagai-morikazu.jp

Cafe Toukasou (D)

1-38-11 Kanamechō, Toshima-ku

Cat & Cask Tavern (E)

1-32-10 Kanamechō, Toshima-ku

Clark Parker is a salaryman and writer of thetokyofiles.com, a portrait of Tokyo through the lens of art, architecture, history and urban design. Since moving to Japan in 2011, Clark has become increasingly convinced that Tokyo is the best city in the world, and is intent on proving it.