September 23, 2010

In Good Health

Compared to the dysfunctional American system, Japanese healthcare delivers the goods

By Metropolis

Originally published on metropolis.co.jp on September 2010

Health insurance reform in the US has been, and continues to be, a complicated affair. Before, during and after the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. “Obamacare”), the amount of furious blogging, protest, screaming and yelling was almost surreal. But in Japan, I have never witnessed such turmoil, and I doubt I ever will. Contrary to my first impressions, the national healthcare system works well—and the US would do well to emulate it.

When I arrived in Tokyo 16 years ago, I still had my expensive Blue Shield insurance, assuming I would only be in Japan a year or two. One of my first instances of culture shock was learning that enrolling in the national health insurance system was considered mandatory (although that’s not to say everybody does), and that the level of coverage was the same for all. As for the premiums, while the amount might vary based on which ward I lived in, the Japanese government otherwise determined how much I would pay based on my salary.

My first few years here were great salary-wise, and as a result, I ended up paying nearly the maximum for my Japanese health insurance—over ¥500,000 annually. Based on my age, my excellent health and the type of work I did, this didn’t make any sense to me, and I spent many hours discussing this with the personnel at my ward office. Needless to say, this led nowhere.

Meanwhile, as I stayed on in Japan, my US premiums increased year after year. As the insurance company constantly reminded me, “Costs for medical care continue to rise,” and there was “no choice” but to pass those costs on to customers. At one point, I was spending over ¥1 million a year to cover my health insurance in both countries.

Eventually, like many other Westerners I knew, I stopped paying my Japanese health insurance premiums. After a few months, I started receiving letters from the ward office with angry red kanji demanding I pay up. My friends told me to ignore the letters. “Eventually they’ll just write you off,” they said. Better yet, “Move to another town and don’t register for health insurance; they’ll never know.” I still see this type of “advice” littered all over gaijin discussion forums. Maybe everyone else has been lucky—I wasn’t.

When I went to America for six months to take care of my sick mother, the ward office found out my bank account info—to this day, I don’t know how—and took ¥1 million to cover unpaid premiums. From that point on, my premiums would be automatically deducted from my account. If I wanted to stay in Japan, I had to find a way to live in harmony with the system. I investigated all kinds of alternatives, but finally decided the best thing for me was to accept it. I let go of my precious American insurance, which had become cost-prohibitive—and soon after I did, I began to discover the value of the Japanese scheme.

When you apply for health insurance in Japan, you aren’t given a blood test or interrogated about your health history. This means, in essence, that even if you have cancer or are HIV-positive, you won’t be denied coverage. Once in the system, you don’t have to wait in fear to find out whether certain procedures or tests will be approved by some God-like doctors in ivory towers. You can also choose your doctor and/or the facility where you want to be treated.

Another valuable feature of national health insurance in Japan is, the less you earn, the less you pay—and you still get the same level of care and coverage. In America, insurance companies bide their time until you get older so they can raise your premium dramatically, all without the least concern for how you will pay for it.

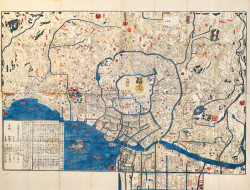

Illustration by Eparama Tuibenau

It’s true that, statistically speaking, the older you get, the more health problems you have. But why should anyone have to go broke to pay for health insurance—or, worse, go without? When I first came here, I thought it was insane that I should have to pay more for premiums because I was earning more. But now that the work isn’t coming in like it used to, my premiums are actually affordable. More importantly, there are now more excellent clinics that have English-speaking doctors who accept national health insurance (at the same time, there are some “private practice” doctors for the foreign community that do not). This year I had a number of procedures done, including an MRI (that I requested). It cost about ¥10,000, as opposed to US$1,500, and in the States I would have had to have been “approved” before the doctor could have ordered one. Here in Japan, I ask, I receive.