May 22, 2024

Indelible Bonds: The Revival of Japanese “Tribal” Tattoos

The recent revival of Japanese tribal tattoos spreads awareness of the plight of its Indigenous people

By Kim Kahan and Jessie Carbutt

Tattoos hold a complicated place in Japanese society. While Japan famously has a longstanding taboo against tattoos, Japanese-style wabori tattoos are popular worldwide. However, wabori isn’t the only tattoo style originating from the Japanese archipelago. The recent revival of Jomon and Ainu tattoos spreads awareness of Japan’s Indigenous peoples.

Unlike the Yamato Japanese population, who associated tattoos with crime, Ainu people and historical Jomon people embraced the art of tattooing. The invading Japanese attempted to crush the tradition of tribal tattoos and for a while it seemed as if they succeeded. But recently, an unlikely revival has begun.

Jomon people were the hunter-gatherer population living in Japan during the prehistoric times (14,000 – 300 BCE). Jomon culture flourished until the arrival of Yayoi people, which scholars believe came from the Korean peninsula.

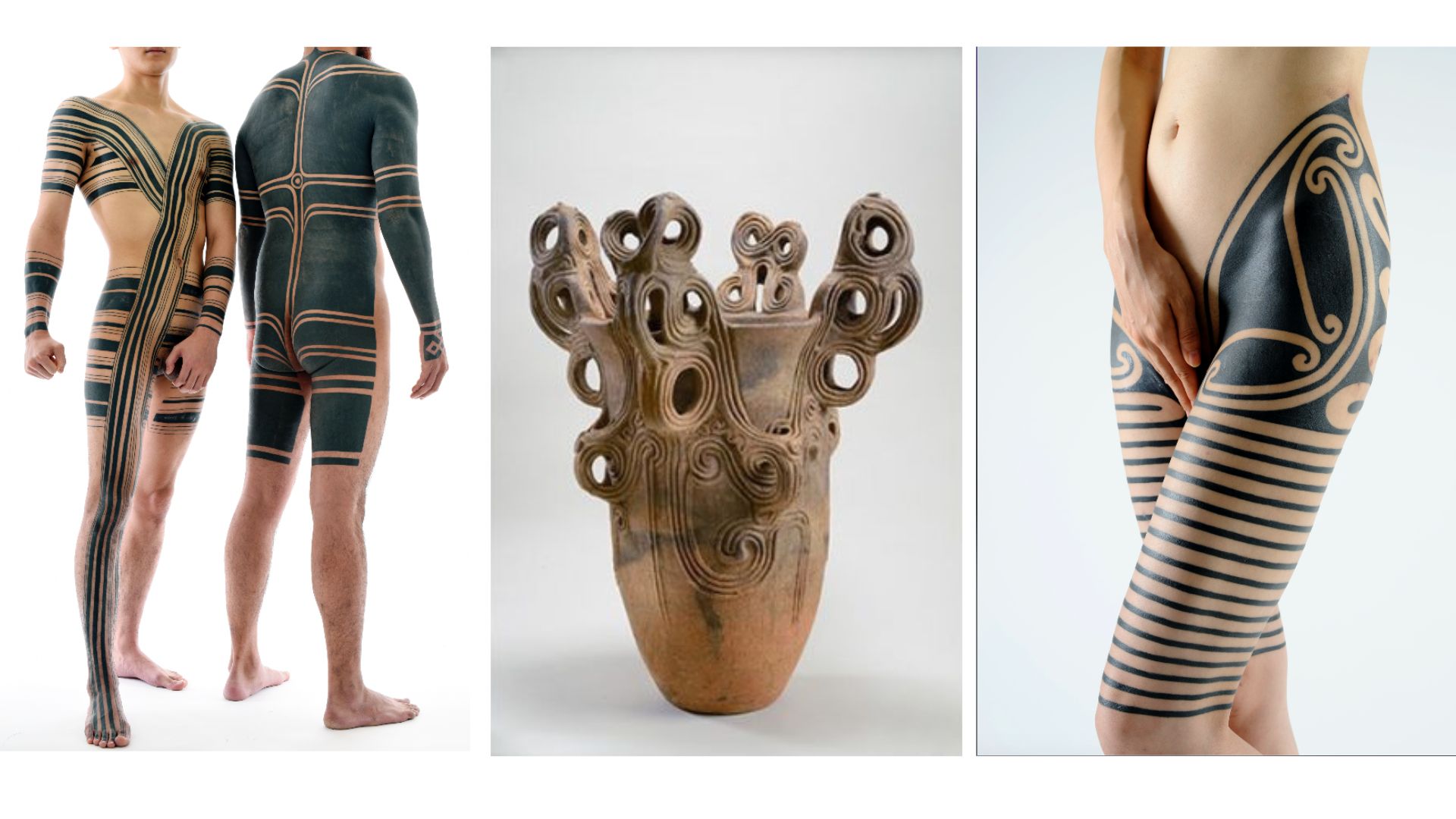

It is widely accepted that the Neolithic Jomon had body tattoos, as evidenced in the clay figurines found in recent years. They were said to vary in relation to factors such as status and age.

Today, neo-tribal tattoo artist Taku Oshima has become especially popular for his Jomon-inspired pieces. He takes inspiration from Jomon pottery, tattooing bold geometric designs on full-body pieces. His Jomon tattoo exhibition with photographer Ryoichi ‘Keroppy’ Maeda was so well received that they held it twice.

As well as Jomon styles, Oshima takes inspiration from his own heritage: Ainu — Indigenous people from northern Honshu, Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kurile Islands — who were probably influenced by the Jomon peoples. Ainu women had tattoos on their faces, arms and hands, and each tattoo (sinuye) was a rite of passage to womanhood.

The invading Japanese attempted to crush the tradition of tribal tattoos and for a while it seemed as if they succeeded.

In 1799, when the Yamato Japanese attempted to stamp out this tradition of tattooing the Ainu defied them, continuing the practice. This led to an even tighter law, which was passed in 1871. The restrictive policy was aimed at assimilation, forcing the Ainu and Ryukyuans to learn Japanese and adopt Japanese names. The communities were also forbidden to engage in sinuye (forehead, around the mouth and hands) and hajichi (hands) tattoos, respectively. For the moment, the law seemed to succeed.

By the mid-1950s, Ainu and Ryukyus began to refuse the sinuye and hajichi for themselves. In schools and out in society, many Ainu people hid their identity after facing racism and discrimination. In a 2017 Hokkaido Ainu census, 23.3% of Ainu reported that they had experienced discrimination. In the present day, it is nearly impossible to see an Ainu person with a permanent face tattoo.

Despite this, however, it seems that present-day Ainu are increasingly taking chances to reconnect to their (tattooed) roots, even if only with makeup. Mayunkiki, an Ainu artist and musician from Hokkaido, is known for performing with her Ainu music band Marewrew while wearing a traditional facial sinuye. She paints her skin for shows and public appearances and has traveled across the world to exhibit and talk about sinuye. In a recent exhibition at the Sydney Biennale, she explained how she researched her mouth sinuye by meeting Ainu elders, asking them to draw the tattoo on her face as they remembered it. By doing this, Mayunkiki said that she felt more connected with her Ainu roots. It made her think about the erasable connections between Ainu culture, Ainu history and herself.

Hokkaido University’s Professor Jeff Gayman, an educational anthropologist and specialist on the Ainu, adds that Ainu people have traditionally painted tattoos at Ainu wedding ceremonies, which have seen a recent revival.

What does this present-day revival mean for these communities?

“As acceptance of tattoos increasingly becomes an element of ethnic revival of peoples throughout the world, it’s likely that Ainu, too, will turn more and more to this embodied symbol of their Indigenous identity,” says Gayman.

Taku Oshima says that as a part-Ainu neo-tribal tattoo artist, his reason for starting the Ainu designs lies simply in the fact that he feels it is a natural progression for a neo-tribal tattoo artist who is based in Japan. He replicates the designs by referring to old drawings and pictures of past sinuye and even counts Ainu people amongst his clients. At this point in time, however, Oshima states that he has yet to receive feedback from the Ainu community as a whole regarding his recreations.

Ainu sinuye obviously holds a deep meaning for these communities and it is important that artists and customers alike are aware of this before understanding a sinuye.

“If this were a different country, there would probably be more of an exchange of opinion,” he notes. “The general population — including the Ainu of today — are very conservative when it comes to tattoos. I think this is the fault of Japanese society.”

On the other hand, Gayman and other experts we consulted pointed out the risk of cultural appropriation, noting that alongside increased awareness in aspects of Japan’s indigenous communities comes more opportunity for cultural exploitation. In what is a sensitive subject, Ainu sinuye obviously holds a deep meaning for these communities and it is important that artists and customers alike are aware of this before undertaking a sinuye.

In the case of artists such as Mayunkiki, the act of replicating facial sinuye brings them closer to their Ainu roots. While the only traditional Ainu tattoos that Taku Oshima has been requested to do are on clients’ hands and arms, it may indeed only be a matter of time before the facial sinuye see a righteous comeback.

(Originally posted in 2022)