December 6, 2019

Kusama: Infinity

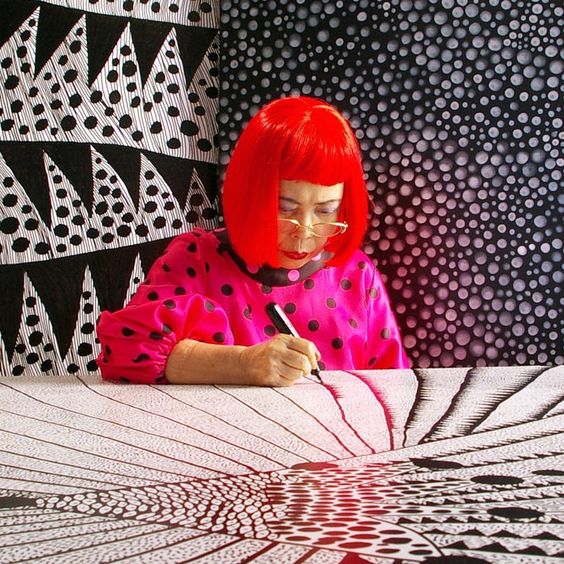

New documentary sheds light on one of Japan’s finest artists

Given the fascination that the public has with Yayoi Kusama’s work, it came as no surprise to hear there was a documentary about her coming out. For director Heather Lenz, though, getting the project off the ground initially proved very difficult. She began working on the script back in 2001 and started pitching the idea to organizations soon after. At the time the queen of polka dots wasn’t as popular as she is now and subsequently, there was little interest in investing in the film.

“I had to try and convince people she was a worthy subject,” recalls Lenz. “I remember being asked by one female executive why I would want to make a movie about a foreign woman. This came from someone in a very powerful position at Maverick Films, a production company founded by Madonna who had of course starred in Evita, a movie about a foreign woman. It was surprising to hear that from one of her gatekeepers. I realized that those in a position to green light projects are more conservative. They don’t want to take risks even if it’s a good idea.”

Lenz was essentially ahead of the curve, realizing the huge potential of the story before most. She became fascinated with Kusama after learning about her in a sculpture class while studying fine arts and art history at college in the early nineties. Though originally drawn to her unique collection of work, the more Lenz learned about the eccentric Japanese artist the more fascinated she became by Kusama the person and her intriguing backstory.

It was the strength of her art that first attracted me to Kusama, yet over time, the thing I became most impressed with was her tenacity.

Born in Matsumoto, Nagano in 1929, Kusama had a traumatic childhood. Her physically abusive mother would often send the young Yayoi to spy on her father in flagrante delicto of his extramarital affairs, the result of which meant Kusama had an aversion to sex. At the age of ten, she started to experience vivid auditory and visual hallucinations, including seeing polka dots, for the first time. She was subsequently sent to a psychiatrist who encouraged her to pursue art.

This was something her mother was opposed to so Kusama had to finish her pictures quickly before they were taken away. She studied nihonga (Japanese-style painting) at Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts but soon grew tired of this distinctly Japanese style. In her mid-twenties, she wrote to Georgia O’Keeffe asking her how she should “approach this life?” The “Mother of American Modernism” replied suggesting that Kusama head to America. And so, she did, spending a year in Seattle before moving to New York a year later.

“It was the strength of her art that first attracted me to Kusama, yet over time, the thing I became most impressed with was her tenacity,” Lenz tells Metropolis. “A young Japanese female moving to New York by herself in this age would be considered bold, at that time you have to say it was remarkable. In many people’s eyes a women’s role then was to get married and have children. Painting would have been seen as nothing more than a hobby. She knew the difficulties she would encounter and the prejudices she would have to deal with, but still had that drive and ambition to go out and do what she did. I believe she deserves so much respect.”

Lenz’s 80-minute documentary pays homage to Kusama while also focusing on her personal troubles and the obstacles she faced as an Asian female in an industry dominated by white males. Her struggles against racism, sexism and other psychosocial stressors further exacerbated her own mental disorders leading to suicide attempts, including the time she threw herself out the window of her New York City apartment. In 1975, after returning to Japan, she admitted herself into a psychiatric hospital where she has been voluntarily living ever since.

Through interviews with her peers, friends and curators, it becomes clear that the iconoclastic artist wasn’t always the easiest person to work with. Ruthless yet sensitive, she also provides several anecdotes herself in the film. We hear about her outlandish “happenings”, often involving nudity, as a protest against the Vietnam War and when she staged “the first homosexual wedding ever to be performed in the United States.” She speaks about being ripped off by other artists such as Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol, and about her relationship with fellow celibate Joseph Cornell, the legendary reclusive American surrealist.

“She always answered my questions,” says Lenz. “People told me about this huge presence she had, and I definitely felt that every time I met her. I remember the first time, I was super excited ready to greet her with a 90-degree bow and she just came out of the elevator with her red wig and polka dots, reached out her hand and started speaking to me in English. When we were done, I told her it was the greatest day of my life and she replied in kind. Of course, I know she was just saying that to be nice, but it was lovely to hear.”

Getting to that point hadn’t been easy for Lenz. When she called Kusama Studios in 2002 to arrange an interview through a bilingual friend, she was asked what TV station or theater it would be shown in. “I was naive and overconfident, thinking they would be as enthusiastic as me,” she says. “Unfortunately, they didn’t understand the idea of a passion project or independent film.” Permission was denied and it would be another five years before she got to sit down with her hero.

There were several other issues along the way, particularly the heavy financial burden on both herself and producing partner Karen Johnson. Determined to get the job done, they persevered. As Kusama’s popularity grew, particularly following her exhibition at Tate Modern in London in 2012, the pair knew how important it was to complete the project before another filmmaker swept in and took the idea. That pressure intensified in 2014 when the Matsumoto-native was named the world’s most popular artist. Four years later Kusama: Infinity was screened for the first time at the Sundance Film Festival.

“When I first decided to make this film, I felt her contributions to the American art world hadn’t been properly appreciated or analysed,” opines Lenz. “Back then, I didn’t expect her to become as famous as she has but obviously, I’m delighted that she’s had so much success. Having struggled for so long, you can see how much it all means to her. As a female director in such a male-dominated industry, it’s wonderful to see this strong Asian woman who had to overcome so many challenges reach the top because she never gave up on her dream. She’s inspirational.”

Kusama: Infinity opened in Japan on November 22.