When it comes to Japan’s image in the global eye, kawaii—the “cute-ification” of just about everyone and everything—is a staple. However, lesser known is moe, an emphasis on the emotional response to fictional characters, as opposed to the characters themselves.

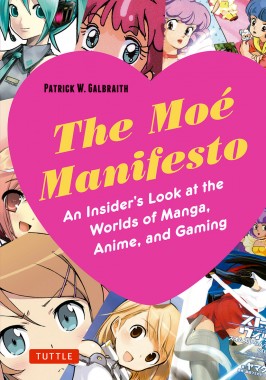

The moe phenomenon has been misrepresented and stigmatized as bizarre overseas. But Patrick Galbraith, author of The Moé Manifesto, the world’s first English book on the attraction, sets the record straight.

“Moe—which is the noun form of the verb moeru (which can mean ‘to sprout’ or ‘to burn’)—is a response to fictional characters,” explains the American author. “It has the connotation of something that gets your motor running.”

“There’s a lot of misunderstanding,” he says regarding fans of manga, anime and game. “It’s easy to look at images of Japanese men embracing pillows with their favorite characters and say, ‘Man, those guys are weird!’ It’s a joke; we laugh and move on.”

“The Moé Manifesto is an attempt to talk with people on the inside—creators, fans and critics of manga, anime and games in Japan—and get their perspective. It’s a manifesto in the sense that it’s a political statement: let’s take people and their lives seriously. Rather than point, laugh and dismiss, let’s listen to them and respect that we might not understand it immediately.”

The moe style is characterized by exaggerated features, such as unnaturally huge eyes and nonexistent mouths and noses. First used in girls’s comics, these elements were introduced to emphasize characters’s emotional responses, and were later adopted in men’s manga and anime, through which they became a standard.

“One interesting result is … ‘anti-realism.’ Cute girl characters don’t exactly look like real women. You can have characters that are attractive without any comparison to or connection to the ‘real’ thing.”

But exactly how important is sexual fantasy to moe? “I posed that question to Honda Toru,” Galbraith says of the moe guru. “He married a character from a PC game. He was attracted to her sexually, sure, but there’s something more to it. Honda describes that ‘something more’ as love.”

What surprised the author, though, was how robust the discourse on moe is in Japan. “Many of us can regonize the allure of comic book and cartoon characters, but how often do you hear people talk about marrying them—and what that might mean socially and economically? Or advocating [a] sexual orientation toward fictional characters?

“What surprised me most was how serious people took their relationships with fictional characters, which were described to me as life-saving—a reason for living, or an alternative way of life.”

http://tuttle.co.jp/products/show/isbn:9784805312827/language:en