July 2, 2016

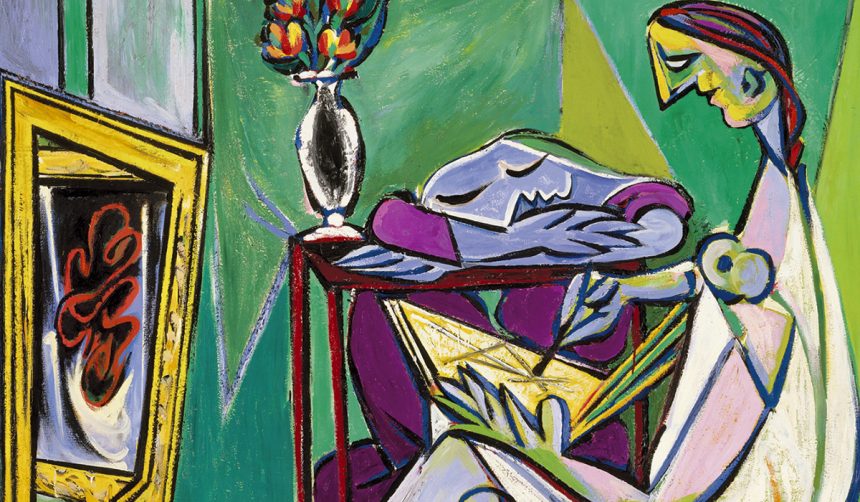

Masterpieces from the Centre Pompidou

Classic art in the midst of modernity

By C. B. Liddell and Abi Buller

When I first saw the Pompidou Centre many years ago on a visit to Paris, my first impression was that it looked like a giant piece of plumbing or the back of an old fridge. When I entered and saw the collection of 20th-century art, it was certainly not one of the most aesthetically inspiring moments of my life. But, in the context of an “overly beautiful” city like Paris, which is always in danger of crystallizing into pure cliché, it seemed to make sense as a way of keeping things edgy, gritty, and unpredictable.

Tokyo is quite a different city, obviously. It’s much more modern—so much so that there’s a hunger for anything pretty and decorative. This is something that also feeds into the city’s artistic tastes. It is therefore interesting to see how the exhibition “Masterpieces from the Centre Pompidou” deals with these challenges.

First, the choice of venue is a good one: the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Art in Ueno Park. With its surrounding trees and somewhat retro modernist architecture, the museum has a relaxed vibe that complements and offsets the strident quality that much 20th-century art has.

Another good move is that the organizers of the exhibition have eschewed an overly intellectual approach. Exhibitions of modern art often feel a need to justify themselves by going for a big, intellectually taxing theme, often one that seeks to “reinvent the wheel” of artistic interpretation. This can often make for tedious exhibitions.

Luckily, “Masterpieces from the Pompidou” takes an unashamedly populist, free-form approach, presenting us with an eclectic selection of varied artists, one from each year for the period covered—1906 to 1977 (the year the Pompidou opened)—with no artist selected twice.

This is a sensible and entertaining approach. It’s almost impossible to unify the chaos of 20th-century art, so it’s best to simply embrace the diversity and make it into an erratic year-by-year odyssey.

This reliance on a timeline also allows the visitor to glean additional interest by considering the historical context of certain pieces. For example, Gilles Caron’s fairly unremarkable shot of a young man throwing a stone, “Protest on Rue Saint-Jacques” (1968), gains added interest when we recognize that it is representative of 1968, a year of anarchy and riot on the streets of Paris.

For the most part, however, you will find yourself, like me, agreeing or disagreeing with the curators’ choices, as they line up with or diverge from your own tastes. You may even occasionally wonder why a certain piece was selected.

Among the highlights for me was Roger Delauney’s large colorful painting “The Eiffel Tower” (1926), respectful in its form but iconoclastic in its coloring, and Raymond Duchamp-Villon’s bronze sculpture, “The Horse” (1914), with its condensed dynamic form.

Another winning point of the exhibition is that each work is accompanied by a quote from the respective artist. These are for the most part well-chosen, and sometimes even more interesting than the artworks themselves. In the case of Raymond Duchamp-Villon, the quote is, “Instead of immobilizing the mobile, mobilizing the mobile, this is sculpture’s true aim.”

In a way, you could say that the Pompidou Centre has served a similar function for Paris, stopping it coagulating into the all-too-familiar and keeping it slightly chaotic and off balance.

Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Art. Until Sep 22.