March 17, 2022

Rainy Spring Night

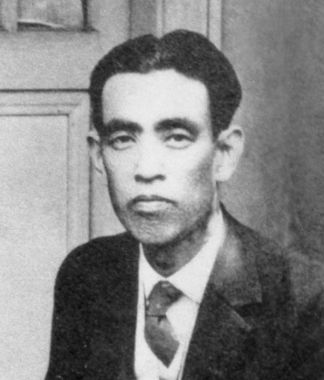

A previously-untranslated short story by Kafu Nagai

Kafu Nagai is one of the great chroniclers of early 20th-century life in Tokyo, but very few of his works have been translated into English. From today’s perspective, this 1922 short story fuses the restrained minimalism of Ernest Hemingway and household theater of Raymond Carver. Silence speaks volumes on this lonely spring night.

Many traditional Japanese poems associate spring with rebirth, awakening, clarity, calmness. Nagai turns tradition on its head. Flowers may bloom bright just outside the rain-shuttered doors of the solitary mansion, but the old couple inside cannot escape the death and loss that surround them, confronted with a rapidly changing society. As Nagai does throughout his broader catalog, he sheds a spotlight on the people left behind.

So take a read. What does spring mean to a lonely old couple on a rainy spring night?

Rainy Spring Night

The shutters were closed that afternoon, so they could hardly hear the falling rain.

The maid called the old couple into the tatami-mat living room. They sat down on cushions that the maid had placed in front of their food trays. The old couple glanced around the room, like perfect mirrors of each other.

Up until just one day ago — up until yesterday’s dinner, the maid always set out a third cushion and tray. But not anymore, starting today. That morning, the couple’s youngest son, Torao, left home to study abroad in the United States.

Until last autumn, when the couple’s third daughter Kiyoko married, the living room had been lively enough to drive its inhabitants crazy. Torao and Kiyoko were close, so they quarreled all the more for it.

A year before Kiyoko’s wedding, their second daughter lost her life to disease. At the time, the living room may have lost one of its members, but the old couple didn’t feel so lonely. Of course, they were saddened by the death of their daughter, but it was a sadness that faded with time. It was also a sadness from which they could easily distract themselves. That was partially because they had been almost impressed that their daughter managed to live past twenty despite needing regular medication her entire life. But more importantly, Kiyoko and Torao always had the power to liven up the house with their laughter.

The old man quietly picked up his chopsticks. “I imagine Torao is eating in the ship around now.”

“It’s raining,” the old woman said. “Do you think he’ll be all right?”

“No, it’s March, so the voyage should be calm. His ship is three times larger than the one I took the first time I went to America. You don’t need to worry.”

“I nearly forgot, with all of Torao’s preparations, but today was the anniversary of my father’s death.”

“March 10th…” The old man trailed off. “Yes, that’s right.”

“I only remembered after you left to send Torao off. Why don’t we visit the grave tomorrow?”

“How many years has it been? Didn’t we do the 12th-anniversary ceremony, what was it, three years ago?”

“Next year should be ten for my mother.”

“Then we’ll have a Buddhist service.” The old man slurped his soup. “This whitefish is delicious. I’d love another helping.”

“Of course, there’s plenty,” the old woman said, glancing at the maid waiting beside the table. “The contents are delicate, so please bring it out carefully.”

“My father also loved whitefish and tofu in his later years. I guess all old men do.”

The old man remembered when his own, now-deceased, parents ate under the soft lamplight, just as he and his wife were doing today. The old man always forgot his age when he thought of his parents, falling into his childhood all over again. But that was only when thinking of his parents. The feeling didn’t last more than a moment. The man was 68, and his wife 59. He was already several years older than his own parents had been when they died. After working in a government office for twenty years and business for ten, he had retired three years ago. But it wasn’t just his parents that were gone. Uncles, aunts, and older friends had all passed away. His children had grown up and left home. And now there was nothing left.

The couple’s oldest son built his own house to live separately shortly after he got married. Their second son worked for a far-away regional government. Their third son went to study in the U.S. Both daughters married out of the family. Now, it was just one couple living in the spacious home, even though their garden alone had more than enough room for a family.

The old man ate his fresh bowl of whitefish soup, but with the second side of rice proving too much, the meal came to a crashing halt. Neither of them ate pickled veggies because of bad teeth. The maid had worked for them for the last seven years, ever since she was sixteen, and knew when it was time to whisk away the heavy serving bowl of rice. The old man and woman took sips of green tea, warming their hands over the fire, while the maid whipped away the rest of the dishes for cleaning, leaving the eight-tatami-mat living room still and spotless in a flash.

The rain came on heavy with nightfall. The quiet dripping ceased, and the shutters began to rattle along with the sound of wind swaying the trees in the garden.

“That’s quite some wind,” the old man said. “I hope the electricity doesn’t go out again.”

He heard the scamper of a mouse and glanced up at the ceiling, moving his gaze over to the alcove. A flowering quince bonsai was starting to shed its blossoms beneath their New Year’s pine decoration and a scroll painting of a snowy landscape.

“I completely forgot to replace the New Years’ decorations.”

“Oh, me too,” the old woman said. “I’m so thoughtless, aren’t I? Without Kiyoko around, we stopped playing cards or bringing out the girls’ spring festival dolls.”

“Let’s replace them. Can you get something from my room? Anything will do. Maybe calligraphy this time instead of a painting.”

The old woman stood up, went to the man’s room down the corridor, and came back with two boxes of hanging decorations.

“I’ll let you choose,” she said.

The old man opened the boxes underneath the lamplight and squinted. “This’ll do. I haven’t seen Baron Kojima’s work in some time.”

The old woman lowered the New Year’s painting from its position in the alcove and placed it in the box. The old man hung up the new decoration and examined it.

“The Baron was in his prime when he wrote this,” the old man said. “It was spring, the year of the Fire Rooster. Not long before I retired.”

Baron Kojima had been the deputy minister at the old man’s government office and later became minister. Currently, he was a councilor in the Imperial Court.

The old woman leaned forward to look at the alcove. “You were with him this time last year, weren’t you? Dealing with that whole scandal? I still can hardly believe it’s true.” Even a full year after the Baron’s daughter ran off with a student, women’s magazines were still running articles about it.

“An evil spirit took hold of her, as they say.”

“From that perspective, maybe we ought to consider ourselves lucky.”

“That’s true. Both of our daughters married into fine households.”

They heard the sound of rain begin to clatter against the shutters. Perhaps the wind changed direction. The old man glanced anxiously over at the shutters, mumbling to himself again. “We’ve sure cleaned up impressively. When Kiyoko was getting married, she had so much stuff that we could hardly walk down the hall.”

“To say the least. Things were so crazy around here when Nagao got married, too.”

“Oh, yes. But now, everything’s all cleaned up. With just the two of us, I don’t even think we need such a big house anymore.”

“You’re right,” the old woman said. “And they’re always going on about, you know, how there’s no more land left for new houses. Perhaps we ought to have a smaller house.”

“Oh, yes. When I bought this house, I purposefully got the adjacent empty lot too, figuring that when my eldest son got married, he could build his own house there. But it wasn’t necessary.”

“Oh well. You know how all young couples want to choose where they live nowadays.”

“When Torao comes back from his studies and gets married, he’ll probably build his own house somewhere else too.”

“I certainly think so. No woman will marry a young man nowadays if she has to live with his mother-in-law.”

“I don’t get that at all,” the old man said. “I don’t see how an incident like what happened in the Kojima family will work out in the end. I heard from the doctor, supposedly, the runaway daughter is like a totally different person now. I don’t understand how she could just take advantage of her family like that.”

“Maybe it’s because kids study too much nowadays. Especially girls. Even Tameko has stopped coming here to play on Sundays.”

“They’re busy with the two kids,” the old man said. “I’m sure they’re worried that if they come once, we’ll expect them every weekend.”

“You’re right, that’s perfectly understandable.”

The two looked at one another with lonely smiles. They could hear the distant sound of a table clock ticking and hot water boiling in the tea kettle.

“Oh, I completely forgot,” the old man said. “I need to write a letter of recommendation.”

He gripped the edge of the brazier and heaved himself up from the cushion. After carefully extinguishing the fire, the old woman turned off the living room light, opened the sliding door, and walked quietly down the outside corridor, carrying the brazier away.

*This is a condensed version of the original story selected for translation