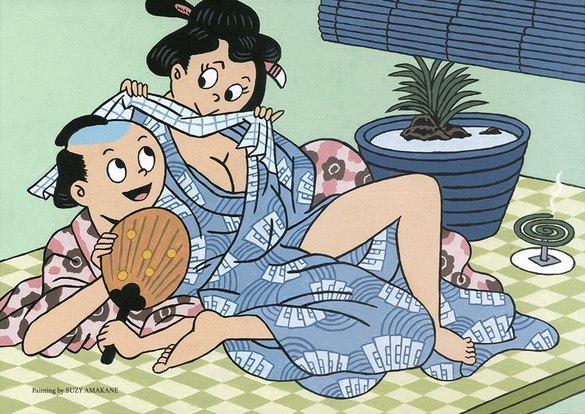

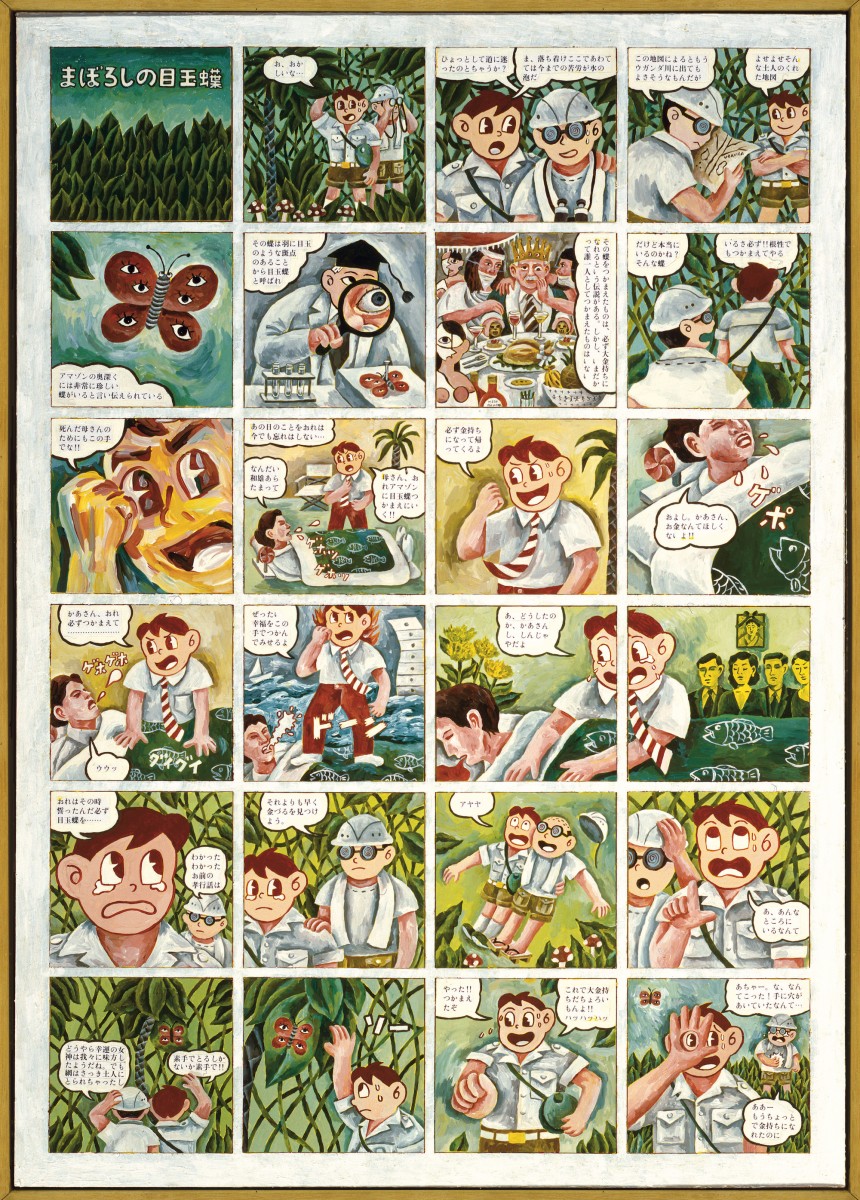

Comic illustrator, painter and part-time professor, Suzy Amakane began his career after graduating from Tama Art University by submitting comics to alternative manga anthology magazine Garo (now defunct but with a cult following) and AX, its descendant of sorts. In the 1980s he pioneered nuri comic, which resembles traditional manga but is a painted strip — the strokes and the physical application clearly visible. His commercial clientele have included the likes of NHK, Seiyu and the advertisement music company Mr.MUSIC. Amakane’s works burst with characteristic color and caustic humor, and though he has followed the commercial road more than some of his contemporaries, his works remain a little subversive. Metropolis sat down with the ink-stained punk to ask about the influences and ideas that have shaped his career.

Metropolis: You were an art student. Now you teach at university. Are you glad you went to art school? Do you feel like your academic career has affected your current one?

Suzy Amakane: I graduated from Tama Art University and taught there. I don’t do that anymore, but I do sometimes teach at Kyoto Seika University, an art school. I was a poor student, like a haguremono (stray), an outsider. The students at art school are so talented, so already my confidence sank because of that. I was lucky just to get in. I didn’t get good grades, either. I had to do something about it. In the middle of my college career, what’s called the “heta-uma” movement emerged and I thought this could be an option for me.

M: So did you start developing your current style when you were a student?

SA: No, not really. [Rummages in his bag and pulls out “A Salaried Man.”] I brought this, my sotsusei (senior project). It’s bad. This was a manga, but while I was making it I was busy with my part-time job and I couldn’t finish. I made it myself, from scratch. You have laptops nowadays, so I could’ve more properly made it now.

M: Who were your artistic inspirations at this time, when you were a student?

SA: King Terry, absolutely. Before [college] I didn’t know about him and [when I discovered him] I thought, so there are people like this. I was quite influenced by him. His real name is Teruhiko Yumura. This is when I was a student, when I was doing my senior project.

M: You mentioned King Terry, who was very active with Garo in the 70s and 80s. He drew a lot of covers for them, and people say the heta-uma (bad-good) style began with him. In an interview, Takashi Nemoto said you are an uma artist with heta flavor. Did you ever draw for Garo?

SA: [Pulls another manga out.] This is called Takarajima, which I was featured in. [Points out his comics, which use thick lines.] My work looked like this before I came to Garo. I didn’t want to draw thin lines. When I brought it to them, I was told, “You have to use a pen.” At that point, I had doubts, I didn’t know what was going to happen. The Garo of the time was Takashi Nemoto and Ebisu Yoshikazu, whom I admired very much. My goal was to get on the magazine. But when I brought my work to them, they said it was no good, that I had to use a pen. Draw manga with a pen. Then I had doubts, thought I couldn’t do it anymore, but I started getting two-page comics on Takarajima, a culture magazine. They picked me. King Terry introduced us. At first I did about three features and they got pretty popular, so after that I drew for them for a long time, one or two-pagers. I thought I found a place to put my work, and there was no need to fixate on Garo. When people hear my name, they might think of Garo, but technically I never worked for them. All I did was some cover design and serial publication in the last days — and that was for a different Garo.

M: Did you ever draw inspiration from comics in Garo?

SA: From King Terry. He doesn’t do much manga, he’s an illustrator. And Shigesato Itoi. They worked together on a manga when I was a student. I thought it was astounding. It was different from other manga up to that point; I looked forward to every issue. Totally different from regular manga.

M: Takashi Nemoto likened underground comics at the time to the punk movement. I would imagine the more promiscuous manga were really radical then. Can you describe what it was like to draw manga at all in the 70s and 80s?

SA: The comics in Garo were certainly crass. Takashi Nemoto has no class, neither does King Terry. They show everything, no censorship. And there were people who looked down upon these works. Nemoto only goes his own way, very charismatic. He doesn’t care about anything else. As for someone like me, whose work is more commercial — I am more wishy-washy, I’ll do other stuff. Takashi Nemoto is pretty much core (hard-core), a maniac. People who like him really like him, though. It was fun to draw at that time, but what we were doing wasn’t mainstream. It was underground.

M: So you didn’t care about how the artworks were received by the general public? You didn’t care about possible criticism?

SA: I’m old and have been doing this for a long time, but with young people — in youth — everyone is that way. The people around me, the people I hung out with, were young [at that time] too; they shared the same sensibilities and intuition. The people I worked with, editors and designers and the like, they thought in similar ways. We were in the same generation. They all did their job because they enjoyed it. If our work was seen by older people, they may not have understood or accepted it. People say that in general, you can only understand people within 20 years of your age. The content you look at is different; as you get older you don’t watch the same things on TV. Give or take 10 years, mutual understanding gets more difficult.

M: Nemoto also said that heta-uma can’t be considered a moment in art history yet because the style has started to disappear, but I feel like you still put the satire and provocative tone [of heta-uma] in your current work. When you draw for a client, have you ever had to compromise how bizarre or edgy you make the artwork?

SA: Yeah, heta-uma already went through a boom. I don’t know if Takashi Nemoto is heta-uma, but King Terry is the founder. As long as King Terry’s around, I think he’s enough.

There are a lot of types of heta-uma — it’s a style, but the contents differ. For example, King Terry drew the beach, erotic stuff, crowds at the beach, when it was beach season. Takashi Nemoto[‘s subject matter] is deep. He likes Korea and the yakuza world.

[Concerning commercial work,] the most difficult thing is adjusting my art to the client’s needs. For example, Nemoto Takashi couldn’t accommodate his subject to the client. He didn’t need to. I’m someone that can do that, so I did it, but when you do it you feel kind of sickened. When I do exhibitions, I am free. But if companies approach me with a theme, I can’t go about it completely freely.

At first, I pretty much drew as I liked. But increasingly I got feedback from companies telling me to tone it down, so as I did more work I learned my limits. At first, there were times I did too much and a client returned my work to me telling me it wasn’t okay, saying, “restrain yourself.” At the same time, people who commission art know who they’re asking. Like Takashi Nemoto used to do commercial work, a series for a Honda bike, maybe, without changing his drawings. He drew for the Benesse Corporation as well. Although he thought he toned it down in that case, the manga he did for that was pretty dirty. He got a bunch of complaints. While he cannot, nor does he have to, restrain himself, his stuff is extreme.

M: You pioneered nuri comic in the 80s. Was this a conscious effort or more an organic process — did you make nuri comic because you happened to like manga and happened to like painting?

SA: An artist called Gary Panter was doing something similar at the time. I thought painted comics would be interesting. There was also an art movement called new painting. Like Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf and Basquiat. Jeff Koons is a little after that. nuri comic isn’t a totally novel thing, really, just a marriage of two things that already existed. I figured you paint pieces anyway, so I just wanted to try it out. But the people around me weren’t doing it. At first, I started with rough pieces, not very meticulous — but as I started getting more detailed, it got very difficult. It was a lot of work. When you seek depth, it takes a lot of time.

M: These days, a lot of manga are digitally rendered. I like the homemade feel of nuri comic. Is this style intentional?

SA: Oh, drawing manga on the computer is a lot of work, too. However, when you use a computer, you don’t know which one is the original. Personally, I prefer analog over digital. Analog has human essence, and that essence comes naturally when I paint. I used to be very particular about drawing by hand, determined it was my way. Now I do digital work too, but I still have doubts about it because of this lack of an original, the vagueness. With digital, it’s hard to recognize one copy as the original. It gets lost; you wonder where it is. I’m attached to hand painting, however. It’s specific. For example, you can sell pictures and prints of an artwork, but your possession of an original gives you ownership. Without that ownership, the value might decrease. Though this isn’t the case for really famous artists.

M: Do you think that more people are accepting of heta-uma these days?

SA: I don’t really know myself. 1980s design is trending. But I wasn’t really part of the design milieu in the 1980s. The 1980s were a really good, prosperous time for people like us — even with our type of work, wild stuff, jobs came. Nowadays, it’s stricter. Back then, no [client] ever asked for a rough sketch, which I have to submit now. For example, when I drew something for a magazine article, all I was told was that my work would go in this space, but that’s changing … Society has become more management-heavy.

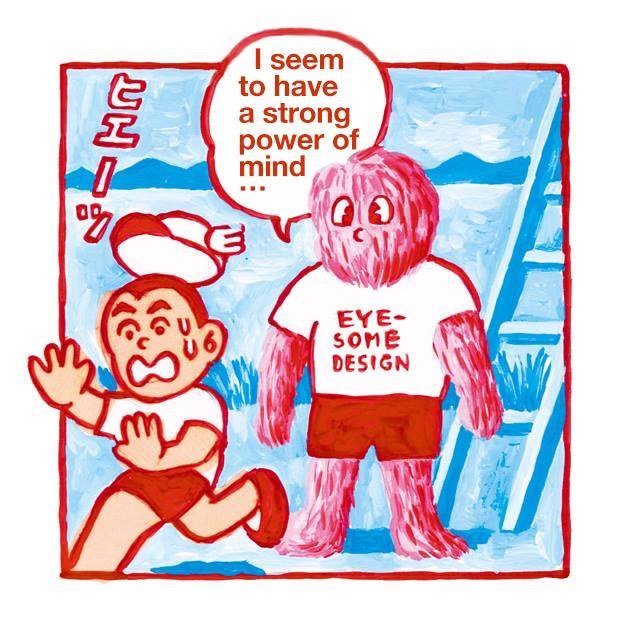

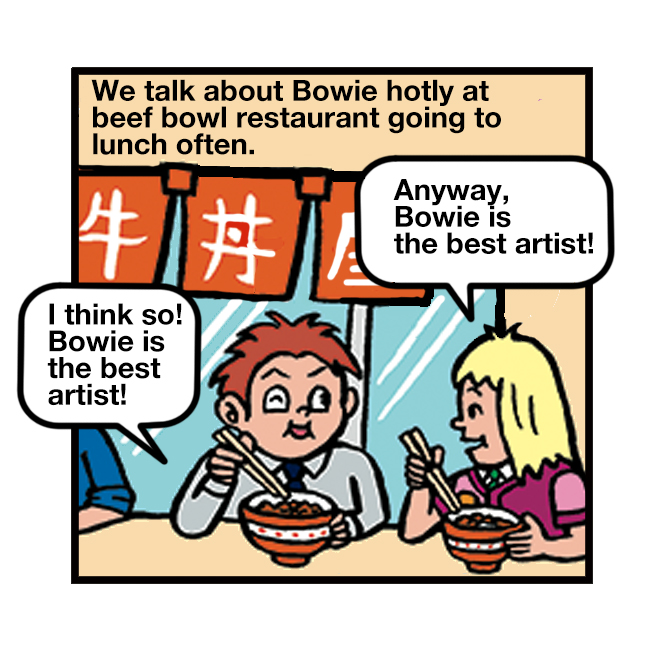

M: You use Instagram to post English translations of your comics. Why do you do this?

SA: There’s a high chance foreign people might look at my Instagram. The results haven’t been that great, a lot of the people that reach out to me through Instagram have just asked me to look at their works. One time, someone asked me if I was doing an exhibition. I wasn’t, so I showed them somebody else’s exhibition. After that, they invited me to their mini-concert at the Bulgarian embassy. I thought, What is this?

M: It’s great how you post your comics in full for free.

SA: Really? It’s okay, I guess. It’s hard to find and buy foreign-language manga online. I want people to see my artworks, and I don’t have that many.

See Suzy Amakane’s works on Instagram and Twitter.