January 15, 2016

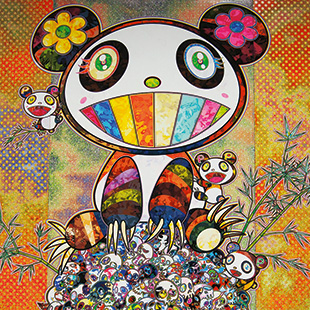

Takashi Murakami: The 500 Arhats

The internationally acclaimed artist proves himself to his homeland

Takashi Murakami is one of those Japanese artists who seem to be a lot more popular with people outside of Japan than within. That’s certainly my experience by quite a wide margin. This is a reflection of the fact that, like automobiles and electronics, the Japanese contemporary art market is skewed heavily towards export, where Murakami’s otaku-flavored pop art plays remarkably well, while he is often dismissed in Japan as tacky and jejune.

His latest big exhibition at the Mori Museum of Art, “Takashi Murakami: The 500 Arhats,” seems to be an attempt to address this disjunction, with his art moving strongly in a direction that references traditional Japanese art.

The 500 Arhats refers to 500 “perfected persons” who’ve attained nirvana … in other words, Buddhist saints. Painting 500 of them has long been considered something of a spiritual exercise for Buddhists, although one wonders just how much of a “spiritual exercise” it was for Murakami, who is anything but a lonely artist working in his garret. Instead, he normally works with a kind of factory setup and dozens of assistants.

For this show, he also drafted hundreds of art college students, who interestingly now have been “planted” with an emotional interest in seeing Murakami’s work accepted by the Japanese art establishment. This is something that may benefit Murakami’s reputation in the long run, as these students become artists, curators, and museum admins.

While many of the images are initially impressive—being large, garishly colored, and with an excellent finish—when all is said and done, they are manga-esque images full of knowing irony. They’re post-modern additions, grafted onto a tradition defined by genuine belief and piety.

The only element that seems to emotionally resonate is the nihilistic note that underscores some of the work, like the Enso (2015) series of paintings, pop-art renditions of the Zen Buddhist tradition of emptying the mind by painting circles, and the impressive Flame of Desire (2013), a spiraling tower of flame holding a cartoonish skull made from carbon fiber, covered with gold leaf.

The real genius in Murakami’s case is not so much his artistic ability—which many “lesser artists” could match or surpass, and which is anyway supplemented by his numerous assistants—but his managerial ability, social power, and geek understanding of how the modern internet-driven media works.

For example, for this exhibition, he has relaxed the usually tight rules about photographing or filming artworks, in the hope that the exhibition will go viral and sell itself through social media.

This embrace of modern, internet-facilitated egoism runs directly counter to the self-effacing message of Buddhism the exhibition is ostensibly about. From one point of view, this represents continuity with the ironic art of Murakami’s past, but from another, it contradicts Murakami’s goal of becoming more accepted by the Japanese mainstream.

His strategy to reposition himself by seeking entry into the pantheon of traditional and respected Japanese artists could well backfire and may further alienate Japanese audiences, who have always been lukewarm to him. This is especially true given his use of religious art to achieve his purpose.

The question remains: will this exhibition mark the point at which Murakami shuffles off his prodigal “geek” image and is welcomed into the Japanese classical tradition, or will he simply be sniffed at as an unkempt interloper attempting to gatecrash a party to which he’s not invited? Whatever the outcome, this exhibition represents a dramatic chapter in Murakami’s career.

Mori Art Museum, until Mar 6. www.mori.art.museum/contents/tm500/