April 6, 2015

The Legacy of JFK

The president’s life is revisited at the Museum of Modern Art Tokyo

It may seem in rather poor taste to hold an exhibition celebrating the life and legacy of President John F. Kennedy in what is, in effect, a glorified book depository. After all , the National Archives of Japan is the kind of building from which Kennedy’s alleged assassin struck on that fateful day in November 1963.

But actually, the Archives—located next to the Museum of Modern Art Tokyo and across from the Emperor’s palace—is a logical choice of venue, because the exhibition focuses on documents, letters, and papers related to the life of America’s most famous and tragic post-war President.

The exhibition—free to the public—opened with much fanfare, including visits from Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and the U.S. ambassador, President Kennedy’s daughter Caroline.

This underlined the importance of the Japan-U.S. alliance in the past, when the world faced the threat of communism, and today, when the U.S. is keen to maintain its superpower status in a fast-changing Asia-Pacific.

Along with the letters, posters, and speech notes are some information boards, videos, and pieces of artwork, including a drawing Caroline did for her father; allowing the visitor to build a picture of a president obscured by his iconic status. What emerges is a man strongly anti-communist—much more than is realized—and a cunning politician with a carefully-crafted “family man” image we now know was largely false.

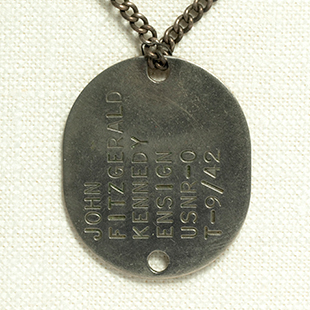

The most interesting items are those focusing on the 1943 incident in which Kennedy had a brush with death when his PT-109 patrol boat was rammed by the Japanese destroyer Amagiri.

The exhibition has a painting of this dramatic event, which set the groundwork for Kennedy’s electable image of “war hero.” But an exchange of correspondence from 1952 to 1953 with the captain of the Amagiri also reveals a more calculating side of Kennedy’s mind. His reply comes a full five months after he received Captain Hanami’s letter, suggesting that he was only interested in replying when he realized the political benefits of appearing magnanimous and boosting U.S.-Japan ties at an important juncture in the Cold War.

Kennedy comes across as sometimes sly, sometimes gung-ho, sometimes even idealistic. He was prepared to gamble and make the grand gesture, as with his decisions to publicly launch the space race and confront the Soviet Union over its placing of missiles in the sovereign territory of its Cuban ally. Several items testify to the tension and paranoia of the famous Cuban Missile Crisis, including Kennedy’s hand-scribbled notes with ‘missile’ circled.

Perhaps the most striking item is a large color photo of Kennedy’s inauguration, which includes around 200 VIPs and luminaries, including former President Eisenhower and future presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon, but not a single non-white face. Quite a contrast with today, when a black president presides over a country where whites are already a minority of new births.

National Archives of Japan, until May 5.