March 31, 2023

The Thorn Puller

Hiromi Ito's debut English-language novel translated by Jeffrey Angles

By Iain Maloney

In the circle of life, Elton John teaches us, there’s more to do than can ever be done. I get the feeling that this is a sentiment with which Ito, the semi-autobiographical protagonist of Hiromi Ito’s The Thorn Puller, would agree. For her dysfunctional international family, Ito is the hub of the wheel, the star around which the others orbit, and the day is never quite long enough for everything that needs to be done.

The Thorn Puller is a clear-sighted, brutally honest portrayal of the pressures of middle age when the generations above and below are oppressive in their needs and the reality of mortality is becoming all too apparent. As a result, it was a huge success in Japan where Ito’s blunt, often funny, always poetic examination of the emotional turmoil of providing care to parents in their final years resonated with many in this aging society. This translation by Jeffrey Angles is her first novel in English.

Much of the plot is based on Ito’s own life though as always with this kind of Japanese literature, it’s hard to know where fact ends and fiction begins. Married to an American man decades her senior, Ito is based in California, where their daughter Aiko goes to school. She also has a daughter from her first marriage, Yukiko.

The novel opens with an indirectly-couched demand that Ito return to Kumamoto, where her elderly parents’ health is failing. Despite living more than 9000 km away, as the only child, custom dictates that she must comply. At the same time, her husband’s health also takes a downturn and he requires surgery; in the U.S. the expectation is that the spouse takes priority. Ito favors her parents but tries to juggle both, bouncing between east and west, never quite being there for either.

As she pings back and forth across the Pacific, she is accompanied by Aiko. While Ito is stuck in the middle, with everyone dependent on her, Aiko is the archetypal outsider. Not quite American enough for the harsh environment of U.S. high school, too American for the conformity of Japanese high school, she is as desperate for a niche of her own as Ito is to escape hers. Ito watches her daughters slowly become women like her; she sits by her mother’s hospital bed looking at her own potential future. The circle of life rolls on.

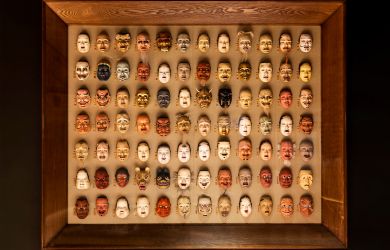

The Thorn Puller’s title comes from Japanese mythology, where, as Angles explains in his introduction, a Jizo is an “enlightened being…worshipped like deities.” This particular Jizo is a statue in Sugamo, a district of Tokyo, “believed to have the ability to remove the ‘thorns’ of suffering that afflict worshippers.” Buddhist philosophy and Japanese folklore are woven into the structure of the book, and the text is alive with allusions to and quotes from classics of Japanese literature. It is a web of references, a work that Ito herself likens more to a poem than a novel, though enjoyment isn’t predicated on prior knowledge. Rather, it is a multi-layered text that rewards repeat readings and deep dives.

The Sugamo statue of Jizo is a family constant, a bond between Ito and her mother. Beside her mother’s hospital bed, Ito returns again and again to the image of the Sugamo Jizo and what it means in her life, both metaphysically and physically, as a landmark in the psychogeography of her childhood. She even brings her husband to the shrine on one of his few visits to Japan and his sneering dismissal of it as immature superstition symbolizes the final end of their relationship.

Ito’s mother articulates the idea that the pain of her final years is punishment for some earlier sin, a manifestation of karmic justice, but she’s unable to name a sin for which she might be responsible. On the other hand, Ito’s daughters are, in effect, being punished for Ito’s choices, pulled “round and round in circles” from one side of the Pacific to the other. The eldest, Yukiko, brought to the U.S. when Ito remarried, struggles horribly to fit in, resulting in treatment for an eating disorder and ongoing therapy. The thorns of suffering are too numerous for one Jizo to pull. The circle of life rolls on.

In spite of all this talk of pain and suffering, this is not a story of misery. Ito wryly presents her tribulations in the style of Buddhist pilgrimages from classical literature. Jizo and other enlightened bodhisattva are frequently portrayed as laughing, because what else can you do when faced with the absurdity of existence? The Thorn Puller is a glorious, immersive read, packed with laugh-out-loud moments and the kind of reflections that anyone who has married across cultures will recognize. Above all, it is a work of optimism, concluding with a Joycean refrain of positivity: “I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive! I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive!” The circle of life rolls on, so you may as well roll with the punches.