March 11, 2021

The 10th Anniversary of the Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami

Commemorating the past and looking to future generations

March 11, 2021, marks the 10th anniversary of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. The magnitude 9.0 quake, the most powerful ever recorded in Japan, hit off the Pacific coast of Japan’s Tohoku region at 14:46 JST, which triggered a tsunami that washed away entire communities and took over 15,500 lives.

With families, homes, businesses, economies and infrastructure shattered in an instant, the people of Tohoku were then faced with the near-impossible challenge of reconstructing their lives and communities. Ten years on, that journey still continues and, while Japan’s scars of grief and loss can never truly heal, the affected communities must nevertheless work towards the future. Today, Japan battles to ensure long-term economic and cultural prosperity for the disaster-stricken areas, and is turning its focus to the next generation of leaders who must now take on this mammoth task.

How do you breathe life back into cities and towns that must build their economies up from scratch? Angela Ortiz, CEO and founder of Place to Grow — a nonprofit organization that works with young people in disaster-stricken Tohoku communities — explains that one of the initial obstacles was financial support. “Companies and governments donated to the ‘safest bet’ towns,” she says. “For example, the towns that didn’t lose as many fishing boats were the first ones to get grants from the government,” she explains. “That caused huge financial gaps between towns — gaps which are still obvious today — with some towns years behind others in terms of revitalization.”

“On top of this, many smaller villages just didn’t have enough people left to rebuild,” Ortiz continues. Japan already faces the nationwide problem of an aging population and young people are increasingly migrating to larger cities such as Tokyo and — in the Tohoku region — Sendai, where there are more study and employment opportunities. “Any kind of crisis just accelerates a country’s underlying social issues and the Tohoku disaster accelerated Japan’s,” says Ortiz. “Many small hamlets lost too much of their population because of the disaster or just didn’t have enough people left who were passionate enough to rebuild. So governments simply merged these places into another town, meaning their specific festivals and culture are now being forgotten.”

We need conversation about this disaster more than we need construction. — Miyata Toshirou, vocalist from the Japanese band BRAHMAN

For towns like Minamisanriku, where Place to Grow bases much of its charity efforts, the situation today is critical. Although the city hall was preparing for the eventual aging of its population, it couldn’t have foreseen such a sudden loss of life caused by the disaster. “Within 20 years, they could lose their high school,” Ortiz explains. “If that happens, the town is pretty much done because no families will want to move there.”

However, for cities with larger populations or those who received larger grants, the past ten years have been a somewhat different story, making the hopes of a prosperous future seem more tangible. One example is Rikuzentakata, a coastal city in Iwate Prefecture. The tsunami virtually wiped out the city and it quickly became an international symbol of the devastation caused by the wave. A solitary tree enduring amongst the debris —dubbed the “Miracle Pine”— became a striking image of hope and resilience.

Subsequently, the city evolved into a hotspot for “Creative Reconstruction” (創造的復興), a term coined by the mayor of Hyougo Prefecture after the Great Hanshin earthquake in 1995. For Rikuzentakata, this involved ambitious plans to raise the land 12.3 meters above sea level, build a memorial museum, sports fields, land for sustainable farming, a large hotel and more.

The long-term aim was to encourage tourism, businesses and residents back to the area, as well as to prepare for the influx of visitors ahead of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. Although the postponement of the games and the coronavirus pandemic stunted these goals, the Takatamatsubara Tsunami Reconstruction Memorial Park is now open. It serves two vital purposes: commemorating the disaster and educating the younger generations about the importance of disaster preparedness and resilience.

Over the next five years, the Japanese government estimates to spend a further ¥1.5 trillion on Tohoku reconstruction, but some people feel it is still not enough. “In the past ten years, the government has poured trillions of yen into reconstruction work already,” says Seiji Komatsu, a former Morioka resident who has since moved to Tokyo, “but, from 2021 onwards, this budget will be severely reduced. People are concerned about forgetting about the disaster and that the process of reconstruction will become slower.”

“From a business perspective,” he continues, “city halls along the coast are unsure whether companies will return to start their businesses there. There’s residential housing under construction, but it’s risky for companies to return to some of the most badly affected areas because there’s still not a strong community.”

As a result, much of the coastal landscapes of Tohoku remain eerily barren despite huge efforts to build breakwaters, raise land to safer altitudes and construct new highways to connect towns. Large plots of land reserved for housing and businesses remain vacant while long stretches of road, dipping and rising into the horizon where the land has been raised, are quiet.

Miyata Toshirou, vocalist from the Japanese band BRAHMAN, remains skeptical of the reconstruction efforts. “We built 12.5-meter breakwaters along the coastline and poured tons upon tons of sand for over a decade to raise the land,” he begins. “But it doesn’t fundamentally solve anything. Proper investigations need to be conducted so future generations can be educated and make the right actions to protect themselves. We need conversation about this disaster more than we need construction.”

The members of BRAHMAN were just one of thousands who rushed to help in the aftermath of the disaster. The band performed charity gigs and continues to support the communities today through the Tohoku Livehouse Project ( 東北ライブハウス大作戦). “The project intends to build livehouses along the coast. So far, we have three venues in Miyako, Ofunato and Ishinomaki,” Toshirou explains. “Music isn’t essential like food or housing, but it isn’t just for dancing and fun, either. Music can heal you, it can stand by your side. Initially, we were doing it for the people who needed music at what was the toughest time in their lives, but now the livehouses are giving people a reason to visit the areas again, helping local tourism and industry.”

“The government and news only report numbers,” he continues “but these statistics can only brush the surface of the trauma these people went through. I’ve spent a lot of time just listening to the locals; sometimes people just need someone to listen to what they are going through. They told me their stories and we cried together and shared their pain. Over the years, our ties have become strong like a real family. Whenever I leave, they always say ‘Please remember’ instead of ‘See you again’ or ‘Please come back.’ For them, March 11 is not a day which marks more than 10,000 deaths. It’s the day they lost their loved ones.”

It’s a poignant reminder that no amount of sand, concrete or tar can replace what was lost, and it’s why Ortiz believes that ‘recovery’ is the wrong word to use. “When you think of recovery, you think about getting better, getting back to what you used to be,” she says. “But after a natural disaster, there’s no going back to what it used to be. The town is completely different. I think ‘rebuilding’ is a good word and ‘revitalization’ is a very accurate and positive word.”

Miho Kasahara, a high school teacher in Morioka, worries about the pressures of the younger generations who are now taking on this task of revitalization. “My concern is whether the hearts of those who were children 10 years ago are healed or not,” she explains. “The students who experienced the disaster when they entered high school seemed more mature and melancholic to me compared to all the other years. Suddenly they couldn’t be kids anymore and had to stand strong.”

Ortiz agrees that there is now a great deal of pressure on the younger generation to be the “poster children of recovery,” but also that this generation is one of hope and strength. “It’s important for the people of Tohoku not to live under this stigma of the ‘victim.’ At some point you choose to say ‘I’m a survivor.’”

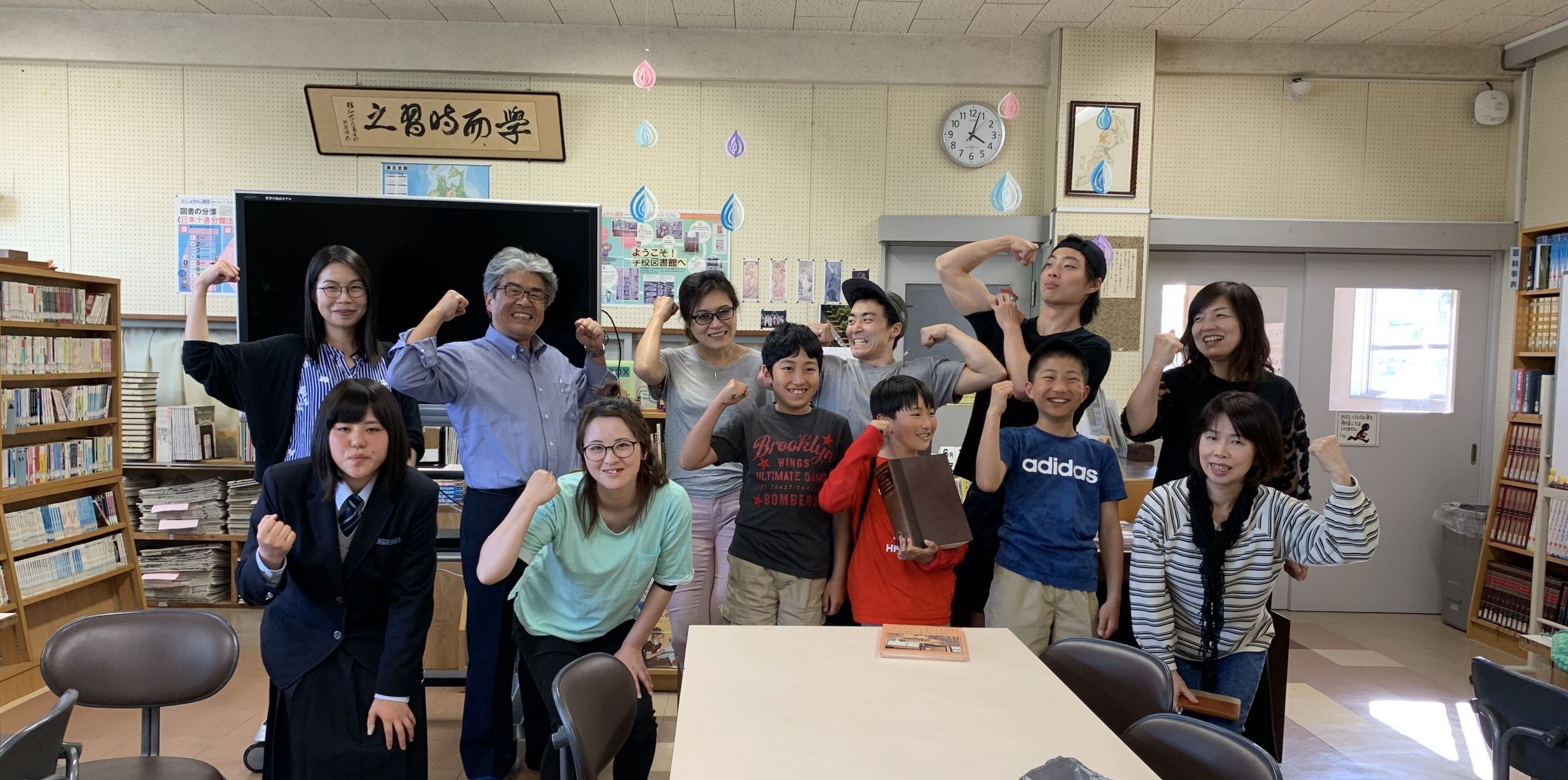

“I believe that all volunteers, not just us [Place to Grow] have helped this generation come to the point where they use the term jiritsu — self sufficient. They want to be the leaders, they want to rebuild and redefine their own futures. Through the support of [Japanese and international] volunteer groups and projects, they’ve made all these amazing connections to companies and countries and cities. We’re talking about partnerships that their parents would have had no idea how to maintain, or their former leadership — or even with some of the current political leadership. I think that they still need partners, people and companies to go up there to chat with them, advise them. We need to connect them to good ideas and encourage them towards a bright future.”

More on the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami:

TOSHI-LOW on the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami

Fumiya Koido: How the tragedy of the Tohoku earthquake sparked a young pianist’s career

How Director Keishi Otomo Found Redemption in ‘Beneath the Shadow’

Place To Grow is participating and hosting events in the days following the 10th anniversary of the disaster. Find more information on Facebook, Instagram, or LinkedIn

by searching “Place to Grow.”