September 7, 2017

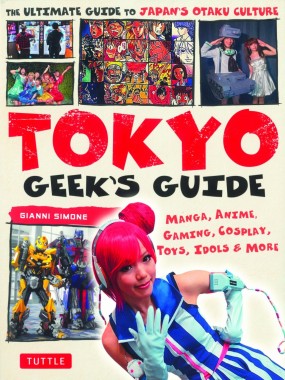

Book Review: Tokyo Geek’s Guide

The new English-language guide to all things otaku in the nation’s capital

More than 30 years have passed since the word “otaku” began to be associated with anime and manga. Many things have changed, starting with people’s attitude toward the word and its implications. Back in 1983, essayist Nakamori Akio used it in a disparaging way when writing about anime and manga fans. Before that, the word “mania” had been used to define someone who was madly in love with and deeply knowledgeable about something, be it comics, trains or weapons. But after Nakamori’s column appeared in Manga Burikko magazine, all those “socially inept young males” who were guilty of seeking refuge in a fantasy world made of video games, toys and cute girls were branded with the otaku label.

Of course that was a very reductive description, and recent books, articles and essays have showed what many people probably already knew: That you don’t have to be a nerdy loser to be an otaku; and that actually the “geeky guy” label is quite misleading for there are as many female otaku out there as there are men.

But people’s attitudes are hard to change, and more than 20 years passed before otaku culture began to be slowly accepted, mainly thanks to the Densha Otoko (Train Man, 2004) phenomenon. This allegedly true story of a 20-something geek who falls in love with a girl was born on the 2channel message board, and from there spread like wildfire, eventually becoming a novel, a movie and a TV series, all of them extremely successful, and showing in the process that these otaku were not so dangerous after all, and some were actually quite cute.

Get Tokyo Geek’s Guide here!

While even today many Japanese have mixed feelings about this subject, foreign fans have never had any problems with the concept and have wholeheartedly used the term to describe themselves. In Europe, Japanese animation first appeared on French and Italian television in the second half of the ‘70s and much of the under-40 generation in those countries has been raised on a steady anime diet. In the United States, already ten years before Densha Otoko, many American fans who attended early anime conventions like Otakon used to proudly display the O-word on their t-shirts. And even in China – where “Astro Boy” first aired on TV in the ‘80s – the so-called “One-Child Generation” born at the end of last century has found ways to circumvent government’s bans and restrictions on Japanese pop culture by pirating copies of popular anime and organizing their own dojin fairs.

Nowadays, of course, the words manga and anime can be found in most dictionaries, otaku culture is celebrated in countless conventions around the world, and Japanese comics and animation are widely available in many languages – not only the giant robots sagas that first became popular in the West but even shojo manga and “boys’ love” stories. Online communities have popped up everywhere, and in many countries we now even have dojinshi fairs and cosplay events. Some people go so far as to learn the Japanese language in order to enjoy manga and anime in their original versions.

Even highbrow culture has fully embraced the otaku world. Internationally renowned artist Murakami Takashi has cleverly exploited manga’s popular appeal; the well-respected Venice Biennale has featured an otaku-themed exhibition (the 2004 Japanese pavilion was called “Otaku: Persona = Space = City”); and even the otaku concept of “moe” is now discussed by cultural critics and sociologists with the same gravity once only granted to wabi sabi and other exotic ideas from Japan.

In other words, today it’s much easier to get your daily fix of your favorite otaku genre. However you can’t really say you have fully experienced otaku culture until you have made a pilgrimage to the holy land of manga and anime. What a trip to Tokyo really makes apparent is how much otaku “sights and sounds” are part of Japanese life, from giant billboards and graffiti to the jingles in some train stations. From the moment you arrive, you just can’t escape its enticing call, as now even at Narita Airport you can find shops selling any kinds of otaku products. Manga, anime and other pop culture icons are now so much embedded in the Japanese psyche that a few years ago the Aqua City shopping mall in Odaiba displayed a huge smoke-spewing Godzilla-shaped Christmas tree, and even Disney went so far as to produce an anime-styled spot in order to attract more people to its Tokyo Disney Resort.

Another thing worth noting is how few concessions Akihabara and other otaku districts make to mainstream western tastes. Though local shops welcome the growing number of foreign customers, many if not most of the things they sell are for local hardcore fans, which means you will probably discover many things you have never seen – which is not necessarily a bad thing. Even as far as Western pop culture is concerned, there is precious little to be found except what the Japanese themselves like (i.e. Star Wars and Disney). And then of course there’s Tokyo itself; a city so unique and different that to many foreign travelers it looks and feels like an alien planet.

This guide has been made with the specific purpose to show you all the things you can do, see and enjoy in Tokyo, and it will no doubt whet your appetite for all things otaku. Hopefully it will be followed by a second updated edition, so if you have any suggestions, criticism, ideas, or you know a place that in your opinion should be covered here please get in touch with me at bero_berto@yahoo.co.jp.

Tokyo Geek’s Guide is available now from Tuttle Publishing.