July 5, 2018

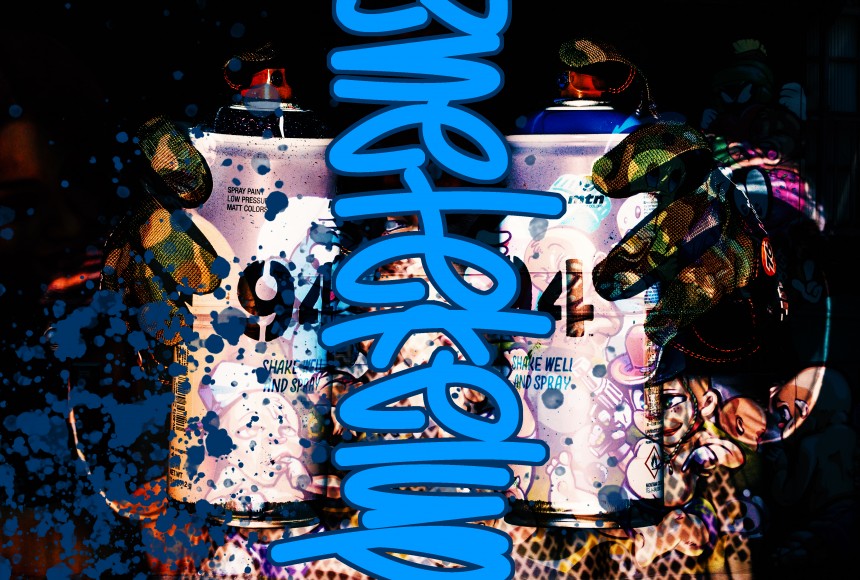

Click, Clack, Spray

The push by Tokyo graffiti artists to bring color to a concrete urban landscape

Tokyo can be a beautiful place — explosions of pink during the spring cherry blossom season, kaleidoscopic neon signs glowing in misty midnight air — but for the most part it’s a vast, seemingly endless sprawl of concrete. Grey, soulless concrete. So many available walls, but so little opportunity for painters and writers to legally express themselves freely upon them. Across the world, graffiti has been, and continues to be, a divisive form of artistic expression, seen by some as nothing more than mindless vandalism while revered by others, sometimes finding protection under layers of plastic sheets.

Historically, “the writing on the wall” can be traced back to ancient times, where the walls of bygone civilizations were found to have markings depicting just about anything, from insults and Christian inscriptions to messages, lists and pictures. The contemporary variant we are more familiar with can trace its roots back to 1960s America, before its adoption into hip-hop culture during the ’70s and ’80s. In Japan, it was the arrival of the seminal 1983 film Wild Style that left a lasting impression on many of Tokyo’s youth at the time, but graffiti was the last of the three fundamentals of hip-hop culture (the others being rap and breakdancing) to gain traction. Although initially influenced by what was being done in the U.S., Japanese graffiti artists began to develop a style of their own in the 1990s and 2000s as the art form infiltrated different aspects of popular culture; even gaming. “Jet Set Radio”, released in 2000 for the Sega Dreamcast, had users taking part in graffiti wars with rival gangs and was set in colorful cell-shaded renditions of various wards in Tokyo. In 2005, Japan’s contribution to the graffiti world was celebrated in a landmark exhibition, “X-COLOR/Graffiti in Japan” at the Art Tower Mito, featuring respected, original writers such as QP, TENGAone and ESOW. Since then, rather than an upsurge in public acceptance and opportunities for the art form to spread out and artists to claim Tokyo’s slabs of concrete for themselves, writers and painters today find themselves continually frustrated by Japan’s lawmakers, with vandalism perpetrators facing jail time of anything between 30 days or several years and heavy fines that can reach millions of yen.

Many of Tokyo’s older, more established writers feel that this has had an effect on the quality and type of work being produced. It is somewhat naive to think that graffiti can ever be eradicated. Those that want to and feel the need to make their mark in public places, will. With time being a factor due to the increased likelihood of being caught in the act however, most writers in the capital rarely go beyond anything more complex than a throw up — a quick, often two-color larger piece of the writer’s name. In Tokyo, the throw up is king. “The art needs more focus,” says YESCA, a veteran of Tokyo’s graffiti scene. “You’re not gonna move forward with just making 20 minute bombs. It’s like a stamp or a logo, pretty much gonna be the same thing, but if you give me four hours or days to work on a spot I can really push my art and see what I can do. It gets boring just doing bomb after bomb. Well, it’s not boring, its fun as fuck but it’s not progressive.”

Wielding a spray can so effectively makes it one of the hardest tools to work with, according to Peter Liedberg, a.k.a. Letterboy, a Swedish calligraphy artist living and working in Tokyo. Having dabbled in his hometown when he was younger, his nerves associated with the illegality of graffiti led him down a different path, but his admiration of what graffiti writers are capable of remains. “With a pen you can lean your hand (on a desk or the wall), with a brush you can use a mahlstick,” he explains. “With a can there is nothing you can hold on to, you are floating in the air … depending on the pressure in the can, how much paint is left, it’s gonna be different. Your pressure is very sensitive on how much paint (comes out). There’s the time: if you leave your can in a certain place for too long it’s gonna drip. Also the distance to the wall, so if you are too far away it’s gonna get blurry, too close it’s gonna be very nice and sharp but it’s gonna start running quicker.”

It’s a skill that many find difficult to hone within the confines of a tiny 1K apartment, so finding spots free from harassment and the possibility of arrest are key to producing quality work. The loss of the famed one-mile wall in Yokohama’s Sakuragicho district, for example, has been of particular significance. Once a popular destination for graffiti lovers and writers of all ages and experience, it was a place to practice and pass down knowledge, skills and codes of conduct. Even featured in the opening episode of the popular hip-hop/Edo period mash-up anime Samurai Champloo, the wall now lies dormant. Having been buffed back to grey it now blends blandly back into its concrete surroundings.

Up a small discreet staircase deep in Nihombashi lies Lettering Avenue. Run by YAS5 the shop is dedicated to providing good-quality paint, and when they can, legal places for it to be used. One of the artists in the shop ZKER points out that “The [Japanese] public don’t have knowledge or experience of good graffiti in the street. They don’t have the exposure to the same degree that people in other countries do. It’s not natural in Japan, they can’t understand which is good or bad. It’s our responsibility to make good pieces, that’s my motivation.” YAS5 adds that, “If all the kids see is tags and they got all this motivation to do art they’re just gonna do tags, but if they see something beautiful they’re gonna have motivation to really try and do something beautiful.” Both feel that being able to have more permanent pieces on public walls from Japanese and overseas artists can help revive the image of neighborhoods that have fallen into disrepair by allowing the artwork to attract visitors. But it’s a hard sell to some people. Districts like Kamata use crowdfunding to keep the area free from graffiti, misperceiving most of it as being related to groups such as the bosozoku (biker gangs).

However, across Tokyo signs of progress are beginning to take shape. Photographer Joji Shimamoto, alongside Kyotaro Oyama, started #BCTION which aims to transform condemned buildings and dead spaces in Tokyo as places for artists to freely express themselves. Shimamoto shares a common sentiment among many involved in the scene that the art should be free and publicly accessible. The duo were recently responsible for commissioning pieces by renowned street artists such as IMAONE that feature on each floor of the stairwell inside the recently renovated and renamed Magnet by Shibuya 109.

Similarly, the BnA Collective have been making their presence felt in the neighborhood of Koenji with their Mural City Project initiative. Murals by artists such as Yohei Takashi and WHOLE9 adorn both public space and privately owned property — all with permission, but also with some concessions. According to BnA Collective’s marketing manager Sabrina Suljevic, the municipality asked that some of the colors be changed. Koenji it turns out has a color scheme: beige. “We weren’t allowed to use certain colors, like fluorescent colors, it had to meld into the area. Originally there were a lot more blues and a lot more pink … they were a lot more vivid.” She explains as she points out Takashi’s impressive, Awa Odori-inspired mural, which sprawls across the shutters of a local opticians. Despite this, she views the support and the fact that they are slowly getting these opportunities at all as an encouraging sign of changing attitudes, and she is hopeful that more are to come.

Moving from illegal to legal may not sit well with some graffiti purists, but on the whole the opportunity to paint and have artists pieces in public is something to be celebrated. “We need public art, art is not only for the museum,” says Lettering Avenue’s YAS5. “People pay to go to museums … children are educated that art is art if it’s in a museum, but I disagree. Art is for everybody and they don’t have to pay money to see it.” YESCA agrees, “Once something is legal it’s not graffiti but it’s still spray paint art. A city like this with no public art is just a shame … (there is) so much talent, so many talented people. Let the people paint some walls man.” Much like anti-drug laws have failed to eradicate drug use, one could make a similar case for anti-graffiti laws. By controlling rather than condemning, perhaps someday soon there won’t be the need for another “X-COLOR” exhibition — the art will be all around us.