December 24, 2014

Whistler Retrospective

The Yokohama Museum of Art celebrates the American artist

Japanese people love Western art—but what they love even more is Western art that’s said to have a Japanese influence. Any artist, therefore, who had a strong interest in Japanese art is assured a warm welcome in these parts. A case in point is the 19th-century American painter James McNeill Whistler, the subject of a major retrospective at the Yokohama Museum of Art, the first one in Japan for 27 years.

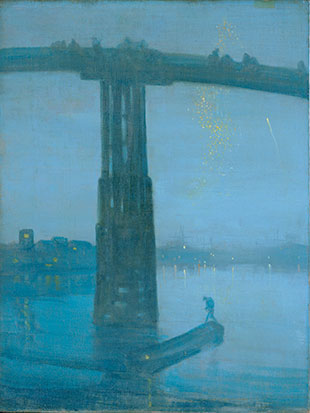

(Photo courtesy of Glasgow Museums)

The exhibition features paintings, sketches and etchings from several sources, most notably Glasgow’s Hunterian Museum, which boasts the world’s largest permanent display of the artist’s work.

During his life, much of which was spent in London, Whistler was often steeped in controversy, both because of his stance against the moralizing tendency of a lot of Victorian art—the Pre-Raphaelites for example—and his emphasis on purely aesthetic elements that this led to.

Never shy of an argument or short of words, in 1878, Whistler wrote, “the picture should have its own merit, and not depend upon dramatic, or legendary, or local interest. As music is the poetry of sound, so is painting the poetry of sight, and the subject-matter has nothing to do with harmony of sound or of color.”

This amoral approach was most famously demonstrated in his portrait of his mother, which he simply entitled Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1. This isn’t included in the show, but the almost equally famous Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2 (1872-73) is. In addition to being a pleasing assemblage of dark and muted tones, this is also a portrait of the great Victorian philosopher and man of letters, Thomas Carlyle.

Although the painting captures Carlyle’s brooding essence, what Whistler was most interested in with this work was the composition and balance of elements that would make it visually interesting—even for those who knew little of its subject.

(Photo courtesy of Yale Center for British Art)

The same can be said for Symphony in White, No. 3 (1865-67), which reduces a painting of his mistress (on the left) and her friend to an elegant and subtle balance of forms and colors.

It’s interesting to speculate on how he developed this attitude. It no doubt had something to do with the West’s encounter with Japanese art.

As ukiyo-e prints and other Japanese artworks flooded into the West in the 1850s and ’60s, Westerners were faced by images where the subject matter was mysterious and little-known, encouraging a simpler and purer appreciation of aesthetic elements.

Whistler was particularly keen on Japanese art and—unlike some painters such as Monet or Van Gogh, where the Japanese influence is more questionable—in his work the debt owed to Japan is clear.

One of the best examples is Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge (1872-75), which transforms the well-known London Bridge into a scene straight out of Edo. The artist’s use of asymmetry and cropping mimic the impression left by the jumbled pages of many a ukiyo-e triptych that had made the journey West.

The real gain that Whistler achieved by his emphasis on aesthetics over content was to give his art a timeless appeal that modern audiences can still enjoy.

Until Mar 1, 2015. 3-4-1 Minatomirai, Nishi-ku, Yokohama. Tel: 03-5777-8600. Mon-Wed & Fri-Sun 10am-6pm. Nearest station: Minatomirai. http://yokohama.art.museum