June 5, 2023

Traditional Japanese Yokai and Modern-Day Pokemon

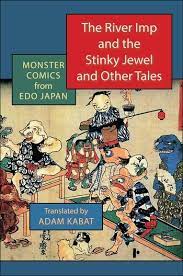

Beyond the monsters with Adam Kabat’s The River Imp and the Stinky Jewel and Other Tales

By Chris Cimi

Monsters, apparitions, and things that go bump in the night. Japan has a rich, storied tradition of folklore with a healthy collective of creatures that haunt the land of the rising sun till present day. Typically more mischievous-than-evil yokai, ferocious bakemono (translating literally to “monster”) and the full-on nefarious oni and akuma (devils and demons) inhabit the coasts, mountains, forests and cities of Japan. Perhaps that’s why, having a population inundated with monster culture from birth, Japan could see the likes of Pokemon and its equivalents not only come to exist but blossom into multi-billion dollar properties.

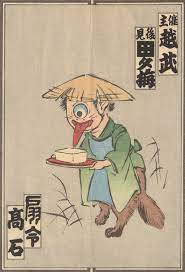

Before we go into more details on our beloved pocket monsters, we would ask you to look towards Adam Kabat’s “The River Imp and the Stinky Jewel and Other Tales,” an excellent English-language collection of late 18th century Japanese-monster kibyoshi picture stories disseminated originally in Japanese in booklet form. It acts as a thorough primer on a great many of these monster characters like the famous cucumber-loving kappa to the proto-uncanny valley tofu boy. A professor emeritus of Japanese literature at Musashi University, a particularly fine translator, and a soul whose spent decades amassing himself fully in the world of Japanese monsters—of the mythological not pocket variety to be clear—the collection of illustrated historical tales published by Columbia University comes compiled and localized by one of the foremost experts of these stories.

An equal boon to Kabat’s impressive preservation of culture, are his generous notes on the Japanese monsters themselves throughout the years, his detailing of the manifestation and circulation of the kibyoshi story books which traded tales of yokai and bakemono throughout Edo period Japan, and his ethnographic recounting of the era which popularized an entire strain of Japan’s myths. Large chunks of “The River Imp and the Stinky Jewel and Other Tales” are dedicated to making sure the reader knows the context of how these folk legends sprung up and spread throughout Japan.

While the origins of many yokai and bakemono were indeed word of mouth legend passed down throughout the years, through the proliferation of kibyoshi picture books these monsters, local legends in their outset, gained wider and wider name-recognition throughout the Edo-period, eventually becoming national mythology. Readers would flock to read these tales of terrifying oni or kuchisake-onna, the slit-mouthed woman. In time, the creators of kibyoshi booklets would put their own spin on Japan’s bestiary of creepy crawlers, adding and changing little details, evolving these creatures along the way. Eventually, more humorous efforts such as stories of Japanese monsters wrestling with make-up in an attempt to mimic human culture, and commercial endeavors, like imagery of the aforementioned tofu boy bearing the mark of famous tofu shops, became as commonplace as the more horrific tales.

It’s here we can make our comparison between traditional Japanese monsters and pocket Japanese monsters. They both existed as commercial efforts, admittedly to varying degrees. While Pokemon do exist more analogously to animals to demons or devils, every few years a whole new batch of Poke critters crawl out of the minds of Japanese creatives and flow into the world through the dual avenues of marketing and sales distribution. While they take on myriad forms, trading cards, playable games, animation, stuffed animals, etcetera, were picture booklets not the trading cards or manga of their day?

Ultimately, what’s the difference between that shiny Charizard card and a limited-print kappa storybook? Both feature cool monster art, both have a smattering of words about said monster, and both were sold all throughout Japan. We could go back to the inception of Pokemon, 1996, before it was quite the 100-billion-dollar franchise it is today, and say kids trading Pokemon and begging their parents to buy those games was the word-of-mouth oral mythology of its day that gave these pocket creatures national prominence just like it had for yokai and bakemono centuries prior.

We’re not sure if Kabat would appreciate this comparison, certainly he did not give his life to studying Japanese monsters and kibyoshi for them to be called Pokemon Cards. What his own ethnographic research does detail though is the Japan of the 17 and 18 hundreds was as monster-obsessed as the country is today, and perhaps that obsession indirectly paved the way for everyone’s favorite capitalistic nightmare franchise kids and adults love today.

To make up for any transgressions, we ask you to read his wonderful, passionate book about yokai, The River Imp and the Stinky Jewel and Other Tales