January 8, 2004

A World Apart

For many foreign parents in Tokyo, providing their children with a fulfilling education is beyond reach. Steve Trautlein reports.

By Metropolis

Originally published on metropolis.co.jp on January 2004

Tokyo offers international students an eye-opening education

Photos courtesy of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

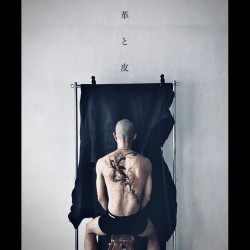

Photos by Martin Hladik

In a modern, spacious high school just outside Shibuya, Japanese and foreign students take classes in rooms that overlook an expansive and leafy park. Lessons are offered in German, French, Korean and English, in addition to Japanese, and the students, who hail from a dozen countries, go on to study at prestigious universities in Japan and around the world. Compared to the cramped and featureless public institutions that dominate the Japanese educational landscape, Tokyo Metropolitan Kokusai High School seems like the perfect place for a child, especially a foreign one, to be educated.

But even at this showcase school, the situation is far from ideal. Of the 240 students accepted each year, less than one-third are from overseas, and admission for those few slots is ultra-competitive. The school was not, in fact, established for foreign residents, but for the children of Japanese businessmen returning from overseas assignments. As such, the curriculum is geared less toward fostering a global outlook than it is to adjusting students for life in Japan.

At once appealing and problematic, Tokyo Metropolitan Kokusai High School is in many ways a symbol of the educational choices faced by foreigners in Tokyo. On the one hand, parents enjoy a host of options, from top-notch private schools to increasingly accommodating public ones to even educating their children on their own. But according to government officials, career counselors, teachers-and the parents themselves-all of these alternatives carry a significant downside, making what is perhaps the most important choice faced by parents one that’s also fraught with difficulty.

For expats who are in Tokyo as part of a corporate or governmental relocation package, and who enjoy opulent Western-style housing, free cars and generous vacation packages, childhood education benefits might seem like a minor consideration. But the savings are, in fact, considerable. Average tuition at six of Tokyo’s leading international schools runs more than $17,500 per year, a figure that doesn’t include transportation, meals and other costs, which can themselves add thousands of dollars. At Aoba-Japan International School in Meguro, for instance, one-time entrance fees and a maintenance charge add almost ¥500,000 to the tab; at the American School in Japan in Chofu, similar fees are ¥700,000. Because companies foot the bill, relocated parents may not even notice these costs, but their employers enjoy multiple benefits. Besides enticing short-term workers with the promise of a Western education for their children, the companies can write off the expenses as a tax deduction.

For many foreign parents who came to Japan out of a love of the country and its people, or who were originally brought over by a company but enjoyed it so much that they decided to stay, such an education is either out of reach or attained only with great sacrifice. And to these long-term Japanese residents, it’s a bitter irony that international education is geared toward relocated, temporary workers. “It does hurt,” says one self-paying Tokyo parent, an American writer and translator whose 14-year-old daughter attends ASIJ and who prefers to remain anonymous. “We wouldn’t be able to do it if we had more than one child.”

What’s more, individuals who do manage to foot the international school bill are not given the same economic relief enjoyed by corporations. “I get no break sending my children to English school in Japan, before or after tax,” says another self-employed father whose two older children attend international schools. “It’s pure, un-reimbursed, out-of-pocket expense.” This parent recalls that he made an effort to persuade administrators at one of his children’s schools to adjust their fees to accommodate his status as a self-payer, arguing that bicultural families-his wife is Japanese-make social, economic and cultural contributions to Japan. He was met with little more than a blank stare.

An inability to pay for an international education leads many foreign parents to send their kids to Japanese public schools, where costs are low but where other issues arise. Among these are concerns about the dynamic of the Japanese classroom, the cultural devotion to groupthink, and the quality of Japanese academics-especially if kids plan on going back to their home countries for college.

But Walter Hutchinson, president of ApplicationAdvantage Online, a US-based firm that provides college admissions consulting for Japanese and expatriates aiming for top US and European schools, downplays such fears. “Admissions officers are not likely to view the Japanese school system as less rigorous,” he says. “Especially if they know that a student who has come through Japanese junior and senior high school levels probably has a very solid foundation.” But Hutchinson acknowledges that the more passive, teacher-centered learning environment is a more difficult obstacle. “If the officer represents a liberal arts program, she might be concerned about the student’s ability to make the transition to an open educational environment, where an academic culture sustained by exchange of ideas demands that students be active free-thinkers.”

And then there are other, more sinister cultural issues. “Japanese school was not an option,” the self-employed father says, adding that this directive came largely from the experiences of his wife. “She tried to make friends with the other Japanese women, but they treated her different and she felt excluded. Then an incident occurred where the principal of our local Japanese nursery school made some comments to my wife that she felt indicated that we did not belong in the Japanese school system.” Kids, too, can bear the brunt of this difference. In her 2002 memoir, actress Anna Umemiya, whose mother is American and whose father is Japanese, told of the harassment she received at the hands of classmates because of her looks. “They would wait for me and chant ‘Gaijin, gaijin’ and sometimes throw stones at me,” she wrote. “While I was in grade school and junior high school, I had no self-confidence at all.” The writer/translator with the daughter at ASIJ had similar concerns. “I believed she would not ever likely be entirely accepted here due to her appearance,” he says of his daughter. “She looks almost entirely Caucasian, and Japanese people who don’t know better treat her as a foreigner.”

Interviews with foreign parents in Tokyo reveal that more affordable and less troubling options do, in fact, exist, if one is willing to be flexible or go a nontraditional route. David Green, a science and photography instructor at Nishimachi International School in Minato-ku and a 25-year Tokyo resident, notes that the last decade has seen a proliferation of international schools in Tokyo. This means more teaching jobs for foreigners-and the fee waivers that come along with them. Green, whose wife teaches fourth grade at St. Mary’s International School in Setagaya, says, “It would be very difficult for me to send my children to international schools without the tuition benefits we get because we work at the schools.”

While many international learning institutions lump corporate payers and self-payers in the same full-tuition category, others, aware of how their fees disqualify much of the population they’re trying to serve, are beginning to offer need-based financial assistance. According to Green, this benefits not only parents, but the schools themselves. “Mainly because the schools do see a need to have a diverse student body and they do understand that there are people who have very valid reasons for sending their child to an international school who just aren’t in a position to pay all or even some of the cost.” Nishimachi has in 2003-04 begun what they call their Outreach Scholarship Program, while the ASIJ and Christian Academy in Japan also offer help for those who can’t afford full tuition.

Faced with exorbitant fees on the one hand and cultural barriers on the other, many parents are choosing a third path and keeping their kids closer to home-literally. “TheÊbest thing about homeschooling is the time families have for each other,” says Angela Bartlett, who operates the Homeschooling in Japan website. Other benefits of parent-led education, according to Bartlett, are the freedom to guide children’s learning, financial savings, and the healthy opportunities for socialization. Her website features links to English-language articles and resources about education in Japan, and it also includes information about how the Japanese, who have scant experience with such a take-charge approach to their children’s schooling, can overcome their anxiety. “I think the biggest hindrance to homeschooling in Japan is the fear factor,” she says. “People are afraid if they do something so unusual that their children will not get into university and that they will doom them to a life of underpaid jobs.” The numbers do tell a bleak story. Whereas in the US the number of homeschoolers is about one million, in Japan, according to the Ministry of Education, the number of junior- and high-school-age children not attending schools is less than 140,000-a figure that includes not just homeschoolers but all categories of non-participants.

While Tokyo’s foreigner parents ponder their options and struggle in a perilous economic climate, help is arriving from an unlikely place: the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Besides the Kokusai High School in Shibuya, Kita Tama High School in Tachikawa is set to open its doors in 2008, when it will offer much of the same amenities as its Shibuya cousin. Meanwhile, more and more public schools are offering classes for foreigners, and Japanese parents themselves are starting to expect an international flavor for their children’s education.

“We have to adapt,” says Tooru Maeda, a planner in the Senior High School Education Section of the TMG. Maeda is speaking about the potentially huge influx of foreigners to the city, but he may as well be referring to Tokyo public education as a whole. Thanks to a declining birthrate, Japan’s capital finds itself with too many facilities serving not enough students, and Maeda, a youthful-looking 42-year-old formerly with the Foreign Ministry, has the thankless task of reducing the total number of high schools in the city from 208 to 180.

The goal is to revivify public education and create a more robust and responsive system, and foreign students are bound to benefit. According to Maeda, curriculum at city schools is determined by the education boards of the individual wards, and already in gaijin-heavy areas like Shinjuku, which has a large Brazilian and Chinese expat population, attention is being paid to their needs: remedial Japanese-language classes for non-native speakers are on offer.

But like many apparently foreigner-friendly aspects of education in Tokyo, the original intent was quite different. These classes were, like the Tokyo Metropolitan Kokusai High School itself, created for the benefit of returnees, in this case the descendents of Japanese who served in China during Japan’s WWII-era occupation. This situation, in fact, mirrors the larger struggles in Japan about the role of foreigners in education and society. Three days after the government declared that new “crime-fighting” measures involved halving the number of illegal foreign residents in Japan in December, the education ministry announced a plan to attract quality students from abroad.

While Nagatacho spins itself into a confused frenzy about the threats and benefits posed by gaijin, people like Maeda who are actually involved in the education efforts show no such conflict. In fact, many Japanese parents are actively seeking a more international influence in their children’s schools. The globalizing of education is a hot topic in dozens of chat rooms and on message boards throughout Japan, and these cyberspace entries indicate a broad-based movement. At one such site, sweetnet.com, a young mother spoke of her-and her son’s-goals. “I want my child to have the ability to get a good job in his favorite country,” she wrote. “I want him not only to understand English, but to learn skills that will enable him to use his language ability. In fact, my child said he already wants to study abroad in the future.

“However, as he’s still only 4 years old, his dream may change.”