October 6, 2020

Atomic Trauma and Family Albums – 75 Years Later

Kazu Sashida's crucial book sheds light on the horrors of Hiroshima

When compared to magazines or photo books, the family photo album is an artifact of intimacy. Through the gaze of the father, mother, grandparent or other intimate relation, the photographic subjects, predominantly children, are depicted as objects of affection.

A half-naked baby, smiling or crying, lies upon a blanket. A child sleeps on a sofa or bed, with his arm lovingly draped across the chest of a sibling or father. These are private moments captured through a family camera, printed on paper and stored in the family archive, the photo album. The album is a memento of fleeting and everyday moments in the cycle of one family’s life and death.

“THROUGH PHOTOGRAPHS,” WRITES SUSAN SONTAG in “On Photography,” “each family constructs a portrait-chronicle of itself — a portable kit of images that bears witness to its connectedness.” The photographs in the “chronicle” do not have to be aesthetically pleasing, though they might be, nor do they have to capture monumental events or moments, though they, also, might.

The image of a child, scribbling upon the ground, is often granted equal importance and real estate as a wedding photograph. Seen through the loving gaze of either a mother, upon the child, or the child, upon the photographer, the album’s unstated and simple goal is a record of familial intimacy for the immediate and extended family.

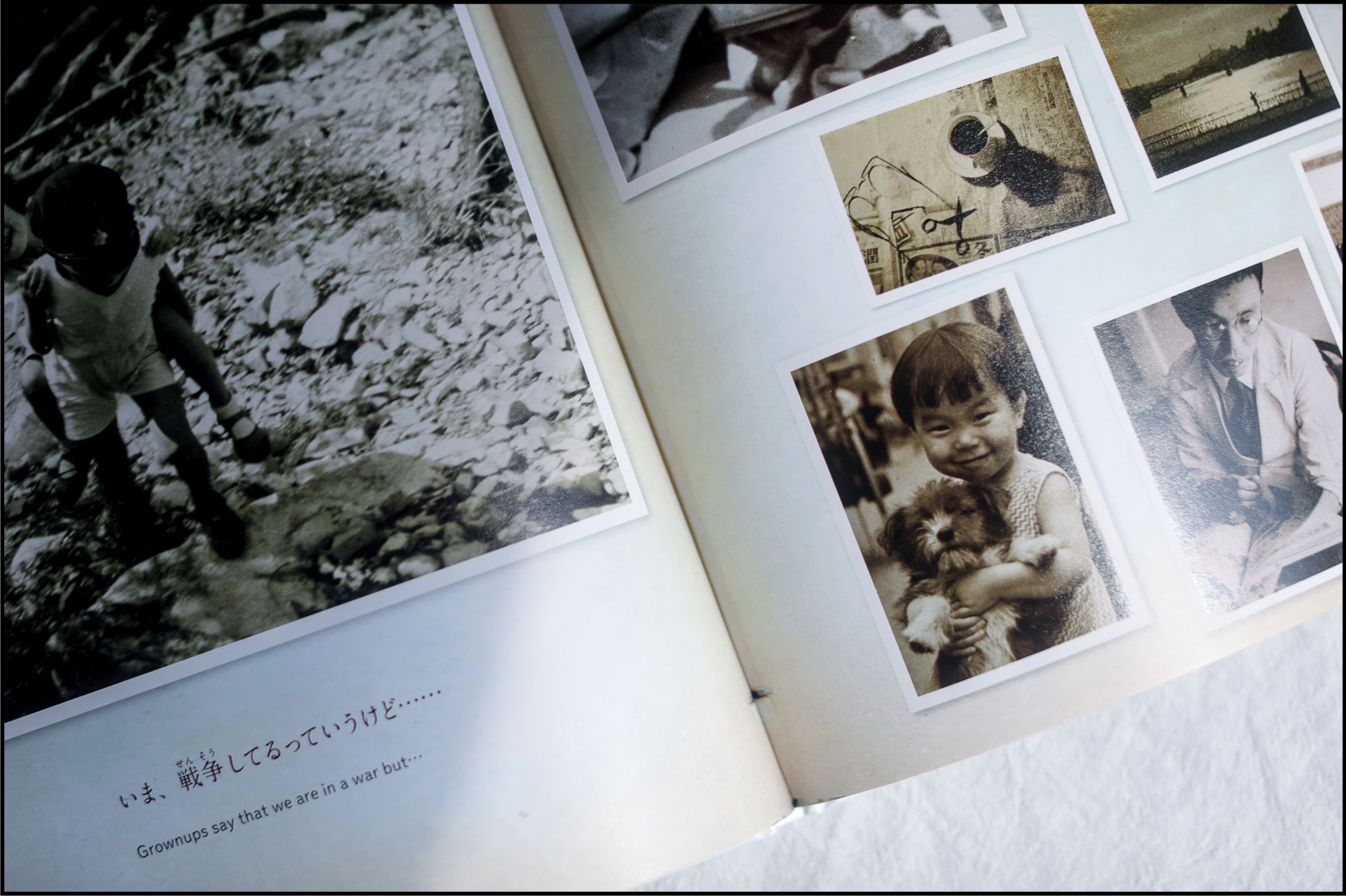

The banality of the family album, as a private memento, is what gives force to Kazu Sashida’s Japanese children’s book, “A Family in Hiroshima: Their Vanished Dreams.” The book resembles an ordinary family album: white-framed photographs, at times crooked, appear pasted upon faux-faded pages. If that does not convince the reader that this, indeed, is a family album, printed staples, and stamps, for good measure, are interspersed throughout.

THE TEXT, IN JAPANESE AND ENGLISH, is written from the perspective of the middle child, Kimiko. The family is, unquestioningly, loving, for the children are usually smiling and often in the company of fluffy dogs and cats. Early on, Kimiko narrates, “We are always cheerful. My dad really loves to take photos of us laughing.” A complimentary photograph shows her older brother, Hideaki, bathed in light, as he sits against a wall. A stuffed toy rests upon his leg and shirtless stomach. He wears the glasses of his father and smiles at the camera. Perhaps, the story goes, these intimate photographs are artifacts to show future in-laws. The images may also quench a future nostalgia, not yet realized, of the family’s earliest years.

Here is a condensed and edited version of 13 albums of one family that lived in Hiroshima, and, in August of 1945, died by the atomic bomb. The father, Rokuro Suzuki, a barber and photography hobbyist, crafted family albums in the 1930s and early 1940s, adorned with the names and birthdays of his children. In these, and other albums, he wrote short and pleasant texts upon the pages, prose reprinted in “A Family in Hiroshima.”

FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2019, the book is currently in its sixth printing. With the commencement of American bombings of Japan, Suzuki conferred his albums upon a family member, outside of the city, for safekeeping. When he and his entire family tragically died in the blast, except for the mother (who would commit suicide soon after), the albums remained as records of their lives before the bomb. In the final pages of the book, we learn of their deaths in painful detail.

The author, Sashida, first saw an image of Kimiko and Hideaki at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, the symbolic center of the bomb’s memory. The site is solemn and tragic, but a necessary and monumental space. The space records, with vivid imagery, objects and testimony, the horrid and tragic details of August 6 and the aftermath. After seeing the images, Sashida told Japan’s national broadcaster, NHK, that she aspired “to create proof the Suzuki family existed, and were gone after the bomb.” She continued, “This kind of destruction must never happen again.”

Steeped in Japan’s pacifist language and discourse, the book calls for ‘No more war’

Steeped in Japan’s pacifist language and discourse, “A Family in Hiroshima,” then, calls for “No more war,” as declared in the Afterward, written in both Japanese and English. This is a universal message made through the most private and particular of modes — the family album.

VEILED AS A EULOGY to one family, “A Family in Hiroshima” is an expression of continued atomic trauma, a lingering sense of wartime victimhood, a higaisha ishiki, or a “victim consciousness.” Though not Japan’s only memory of World War II, the recollection of civilian suffering at the hands of Japan’s “reckless” wartime leaders remains, since the early postwar to the present, central to narratives of the war in public memory.

“A Family in Hiroshima” provides a lens by which to unpack, in the wake of the 75th anniversary of America’s dropping of the atomic bomb, the enduring narrative of the atom bomb in Japan. It sheds light as to who remains central — and who doesn’t — to the nation’s contemporary story of the war, for, as the scholar Kiichi Fujiwara recently wrote, “the choice (and neglect) of historical subjects in a certain community may reveal what the community or society thinks of itself.”

Though any account of the past, whether found in mass culture or a recorded testimony, is selective because it is, by nature, a story of one or many individuals, a family album is distinctly insular.

“Family albums are filled with scenes enabling us to conjure up a now-vanished world encounters and gestures,” writes the historian Jay Winter in “Remembering War,” “which, taken together, describe the stories families tell about themselves.”

What happens, as in “A Family in Hiroshima,” when those private stories are refashioned as national memories?

Suzuki did not, one can safely assume, intend to record the milieu of the time, or to provide a historical artifact for the future researcher. Certainly, he had no way to know that he and his family would be victims of the first wartime usage of the atom bomb. Instead, he produced a record of his family.

One photograph shows Kimiko, on the back of Hideaki, smiling, as is the case in most of the images. Hideaki’s head is face down, covered by the hat of the school uniform, and his back bent over, under the weight of his sister. He walks through a shaded area, littered with small stones and surrounded by fallen timber.

“Grown-ups say that we are in a war but…” Here we find the only mention, in the first half of the work, of Japan’s involvement in a war. The other photographs, on the spread, mirror the rest of the book: the children smile, a cup of coffee rests on the table and the father reads a book.

THIS FAMILY, THE CHILDREN IN PARTICULAR, the subtext reads, was far from the front, barely aware of war and living an innocent and joyous life. The innocence of childhood and tenderness of family intimacy, seen through the lens of a family album, excises the war from our perception of their experiences and lives. These children, the subtext continues, had no part in Japan’s war effort.

Yet the private record of civilians, reframed as a narrative of victimhood, neglects, by design, the suffering of other wartime victims

In “A Family in Hiroshima,” we find a story of a Japanese family that is comprised of civilians of varying ages, depicted against the shadow of a menacing and tragic future. Yet the private record of civilians, reframed as a narrative of victimhood, neglects, by design, the suffering of other wartime victims — whether that be non-Japanese killed in the atom blast or the victims of atrocities committed by the Imperial Japanese Army across Asia.

Though in the Afterword of “A Family in Hiroshima,” we learn of the “Korean, Taiwanese Chinese, and American POWs” killed in Hiroshima on August 6, this is but a footnote. Here we find no malicious intent, for the album is cast, by the author, as a solemn and necessary testament to one family lost in the tragic blast.

Elsewhere on Metropolis:

- Hiroshima: A City of Hope

- The Resurgence of a Japanese Literary Master

- How Director Keishi Otomo Found Redemption in ‘Beneath the Shadow’

Yet we must be wary of the political co-option of the victim narrative. In the 1960s and 1970s, the writer Makoto Oda, for instance, expressed discomfort at the state’s appropriation of the victimization of the hibakusha (bomb survivors), for the experiences of these people had become the experiences of the nation. Though this is not what we find in “A Family in Hiroshima,” the work has been cast within a minefield of politics, nationalism and competing victimizations.

WE FIND NATIONAL MYTH IN THE FAMILY ALBUM, intermingling with family lore and bound with affection and familial love. The story of Kimiko and Hideaki is consumed in national history, something Carol Gluck, a great historian of Japan, has ascribed as “a past imagined in the context of national identity.”

The family album, an artifact of intimacy, when framed as a historical artifact, collapses upon itself; the familial myth becomes national myth, and national myth becomes familial myth.

Nonetheless, “A Family in Hiroshima” is a crucial and accessible work that recollects an ever-salient event through a private, devastating, and moving story of one family. The work is excised of blood but not tragedy so that children, like adults, can read through and witness the experiences of Kimiko, Hideaki and their lives in Hiroshima.

This is a book that everyone should read, for we all must continue to remember the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“A FAMILY IN HIROSHIMA”「ヒロシマ消えたかぞく」Sashida, Kazuko 指田和子, Tokyo Popurasha, 2019, ISBN 978-4-591-16313-9

For more on literature and translation: https://metropolisjapan.com/culture/books/