February 26, 2021

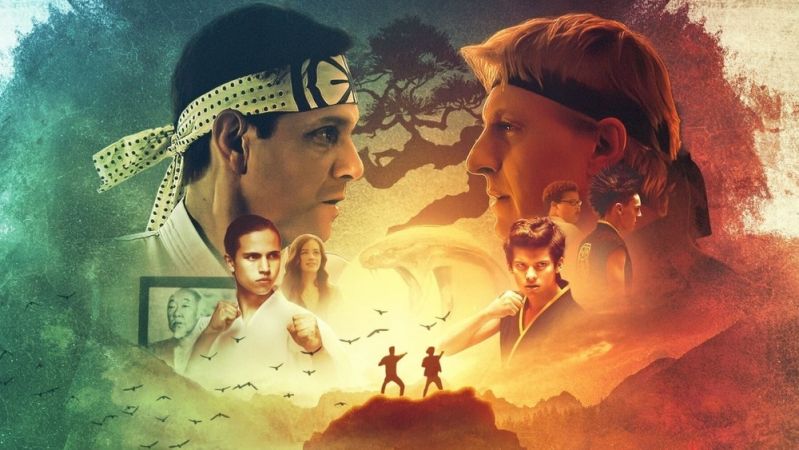

“Cobra Kai” and the American Gaze on Okinawa

How the Karate Kid franchise perpetuates and problematizes an American fantasy

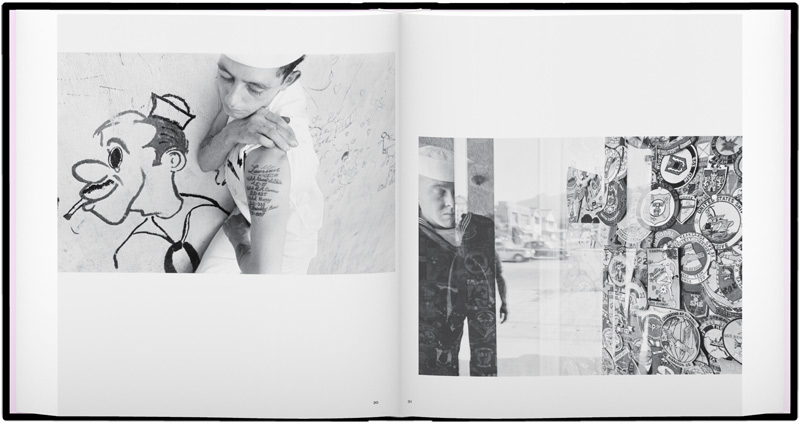

Before me, I have a photograph. It is banal, simple and not very well composed. A man stands in profile, his arms at his sides and head trained towards the right of the frame. A poncho, creased and wrinkled, covers his body, and his head—clean-shaven but worn—peers through the top. He wears a side cap. The man is set against a dark background, the color of which is unknown for the photograph is black and white.

Here is an American service member in Okinawa in 1969, at the height of the Vietnam War. And in this photograph, seen in the work of Shomei Tomatsu on American bases in postwar Japan, the man is gazed upon: hulking, sad, foreign. He looks beyond the frame to something unseen and unknown to us. What is caught in his sights? It is other men, of course, uniformed and American. But it is also Okinawa.

There is an American gaze on Okinawa, which co-opts, exoticizes and fantasizes. It is neither singular nor uniform and is first the gaze of the American service member stationed there. On-base or off, he is swaddled in Americana but looks beyond. He may mistake the woman at the base town bar, perhaps fluent in English and flirting for tips, for the whole of the island population. It is also our gaze, replayed and repeated, altered over time, of pristine beaches and tropical paradises. And it was this gaze I recently found perpetuated, but also problematized, in season three of “Cobra Kai” on Netflix.

“Cobra Kai” is the sequel to the “Karate Kid” films, which, for the uninitiated, tell the story of Daniel Larusso (Ralph Macchio) and his run-ins with a rolodex of karate rivals (most prominently Johnny Lawrence, played by William Zabka). The show portrays Daniel and Johnny as adults—still fighting, only slightly more mature. Larusso is the star in the films, and Mr. Miyagi (Pat Morita) is his karate teacher, mentor and father stand-in. Mr. Miyagi is from Okinawa, so the island chain is a looming presence in the franchise. If New Jersey is Larusso’s hometown, Okinawa is his imagined homeland.

In the new season’s fourth episode, Larusso arrives in Tokyo, a trip taken to save his failing business. Here a fortuitously timed tourism clip of the island chain follows an exchange with a white-suited barman. Alongside a bird’s-eye view of sweeping beaches and greenery, a voice announces, “The nature. The tradition. Spend your four seasons in Okinawa.” It is sunny and tropical, a vacation spot, welcoming to tourists and overlain with English narration.

Larusso soon descends an escalator in Naha airport, set to a hymn of flutes and against a tableau of flowers and small palm tree-like plants. From a taxi, the landscape passes by and a flashback from the 1986 “The Karate Kid Part II” runs. “This looks like the town that time forgot,” Larusso, then a teenager, says as he walks through Mr. Miyagi’s hometown, Tomi Village.

In 1986, the filmmakers wrought Okinawa in classic tropes of an American gaze, which, at times, exoticizes anyone deemed the other. Tomi Village is thus rendered as backward and primitive, and Larusso as a white savior. In a sequence that is as absurd as it is cliché, he rescues a young girl, Yuna, from a storm.

More on Foreign Cultural Impact in Japan:

-

America’s Tokyo: Revisiting 75 Years After the Occupation

-

The Gaijin Privilege Paradox

-

Race Relations in Japan

The actress Tamlyn Tomita, a star of the second film, said in a recent interview, “The only sense of Okinawa [in “The Karate Kid Part II”] is coming through [screenwriter] Robert Mark Kamen’s interpretation of his time spent in Okinawa.” We mustn’t forget that much of the 1986 film was shot in Hawaii, which meant that American filmmakers crafted an already colonized space into imagined ideas of a foreign land.

And yet, for “Cobra Kai,” Tomita—Japanese American, with Okinawan heritage—has returned and helped to craft a more faithful and culturally sensitive representation of Okinawa. Daniel’s reentrance to Tomi Village, set in the present in “Cobra Kai,” is marked by the arrival to Tomi Village Green, a shopping mall, crowded and sprinkled with uniformed American service members. The American Eagle and Red Lobster mark the arrival of coca-colonization, which erases that mythical past for which Larusso longed. But it also erases an Orientalizing gaze, for there is no longer anything to gaze upon.

And it is also here, in this modern shopping center, that the show reverses the power structure of the 1986 film. In the fifth episode of the recent season, Kumiko introduces Larusso to a woman adorned in a pantsuit. It is Yuna, now an executive at a company and now fashioned in a position to rescue Larusso: “I’m about to save your business,” she says soon after meeting. There is something profoundly transformative and subtly subversive about the scene. Yuna is portrayed with agency, no longer at Larusso’s whim, for he is now beholden to her.