May 21, 2018

Don’t Kill the Idealists

Japanese universities are stifling a generation of dreamers

By Masaru Urano

What do you want to do in the future?”

As a side job, I mentor several Japanese high school seniors who want to get into university. My students are fun, witty, unique individuals with keen interests in making the world a better place. They have big dreams about how they want to live their college life, and they’re motivated to work hard for it.

But more often than not, the answer I get on their plans after university is not particularly enthralling.

“I want to get a job at a big company.”

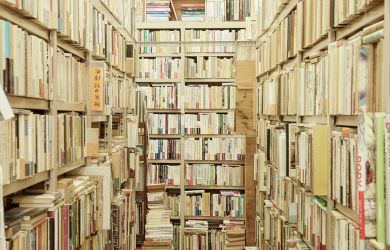

Instead of the standard exam system, where students spend years cramming for the National Center Exam, my students will apply for college through the “AO” system. The system tries to mimic the American college application system by giving students essay questions like “What do you want to do in college?” and “What do you want to do after college?” instead of exams. This new system is supposedly built to bring in students who should be valued not based on their academic merit but on their dreams to contribute to the world. The system attempts to gather students who think outside the box and want to make use of college education for their grandiose dreams.

And that’s the sort of students who apply using the AO system: quirky idealists who don’t conform to the conventional Japanese way of life. Or at least so I thought, until I asked my students about their dreams for the future.Within the confines of “a big company,” there’s plenty they want to do. They want to travel abroad on business trips, or meet many kinds of people or climb up the corporate ladder. But behind those goals there is an underlying idea that is as conventional and unoriginal as it could get: to succeed in life is to get a job at a stable, well-paying company right after graduating college.

I often grill my students on their answers. If you think that the global refugee crisis should be solved and you want to study that at college, how is joining a domestic corporation going to help? Why do you want to land a job in a trading company if your main interest is in philosophy?

The students try their best to justify their future plans, but their responses reveal several depressing premises that plague the Japanese education system today: that college is only a status to slap onto one’s CV, that what one learned in four years in college is worthless in real life, and that lofty dreams are useless in the face of the pragmatic demands of capitalism.

I, as someone who got into college through the AO system myself, and is currently searching for employment through the conventional shukatsu (simultaneous recruiting of new graduates) system, understand that it is common for dreams to fade, for reality to hit hard and shape former idealists into pragmatists. But to think that these ambitious and independent students, who are applying for college through a system that rewards ambition and uniqueness, will go into college thinking that what they do there is worthless, and that at the end of the day they have to give up their dream once they get out of college, is disheartening.

In my capacity as a mentor, I do my best to convince my students that there is more to life than a normal job in an office, that dreams don’t have to die once you are handed a diploma. Hopefully, at least some of my students will be able to envisage a career that carries on the idealistic spirit they have now.