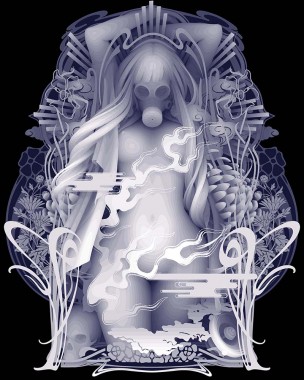

It is difficult to categorize the macabre, beautiful and stark practice of Japanese artist Kazuki Takamatsu. Combining carefully rendered gouache, air-brushing and hand painting with depth-mapping computer graphics, Takamatsu’s manga-esque works are at once hauntingly intriguing and perversely contradictory. Staunchly Japanese while still feeling cross-cultural; enigmatic despite their familiar iconography; poignant but emblematic of pop culture — these are just a few of the contradictions that characterize Takamatsu’s complex images. Their very materiality seamlessly and sensitively straddles old and new.

With exhibitions currently running in both London and Shibuya, the unique practice of the Sendai-born, thirty-four-year-old artist was developed when Takamatsu was still a student at Tohoku University of Art and Design, Sendai. He graduated in oil painting in 2001. As a student, Takamatsu painted different gradations of colour onto plexiglass, but found the style old-fashioned and, ultimately, unattractive. By chance, Takamatsu met a 3-D computer graphics artist who suggested he take up computer-generated imagery in his own artwork. Convinced this was the right medium for his artistic explorations, Takamatsu studied 3-D CG independently. From here, he developed his new style: the unique combination of computer-generated images with hand-painted gouache — a water-media paint a little like watercolour.

The result is an otherworldly representation of multi-layered, doll-like figures which occupy a metaphorical plane between the real and the fantastical. For Takamatsu, it was crucial to have his work reflect that space between the literal and the virtual. It’s a tension he believes colors the lives and experiences of today’s generation: “I believe that this constituted a perfect mirror which reflects the contradiction of the present world in the pure emotion of younger generations, and is ultimately a symbol of beauty.”

It is interesting that Takamatsu characterizes his pieces as things of beauty when, for many, they embody a pervading sense of melancholy, sadness and even violence. Some of his figures — which precariously teeter on the brink between childhood and adulthood — seem lost in despair. Others take on a more deviant, sexualized nature. Like a dark fairy tale, Takamatsu’s work suggests grim, macabre narratives that are at once captivating, frightening and even seductive.

For example, he often depicts iconic female avatars — young girls who seem to have stepped out of a Japanese manga, then given a ghostly treatment. By choosing a ubiquitous trope, the Japanese manga girl, Takamatsu gives his subjects anonymity, like the anonymity we achieve through our online personas. “We now use social media, blogs and other platforms as communication tools,” Takamatsu tells me over email. “Through the handle name and avatar, people don’t know the name, age or sex of contributors, so they feel able to write their true words and emotions.” This exploration of the lines between truth and artificiality is reinforced through Takamatsu’s juxtaposition of mediums — the traditional gouache process, alongside the digitally-rendered CG.

The digital identity of his works does not come from his references alone; his creative process itself speaks to the act of retouching, photoshopping and contouring. Takamatsu acts as a makeup artist, refining the details of his dream-like creations to comply with current standards of beauty and femininity. The mediums he works in are digital make-up, smoothing over imperfections and glamorizing his subjects.

Unlike conventional modes of modern beauty, however, these young female subjects do not pop with pastel tones and matte shades of colour. Rather, Takamatsu exclusively uses monochrome in his work, layering up gradations on the tarpaulin’s surface. This method, known as ‘depth-mapping,’ gives the sense of three-dimensional distance. A shade of grey is chosen for each individual pixel; that shading is decided based on the distance between that pixel and a chosen “viewpoint.” A technique introduced in 1978 by Lance Williams and more commonly associated with Pixar animation and video games, the technique produces corporeal authenticity, as Takamatsu’s images appear to be literal x-rays of his subjects.

Perhaps a childhood growing up in Sendai is what drew him to dark, monochrome colours, muses Takamatsu. “I think people who live in Sendai prefer monotone colours — white, black and grey — when they choose a car and build a house. I, too, prefer to pursue delicate monotone colors in my work.”

Despite his use of black, white and gray tones, there is no doubt that these works exist within a practice that relies on pop culture, and genre styles including New Figurative Art, Pop Surrealism and Post-Graffiti art. This is seen in the galleries that represent him. Corey Helford Gallery, Los Angeles, Gallery Tomura, Tokyo and Galerie LeRoyer, Montreal all focus on artists who delve into creative subcultures often with unusual, surreal works. They are often placed under the banner of fairytale, alternative universe or fantasy.

Having read that Takamatsu was a “self-declared fantasist,” I asked him about the role of fantasy in his work. He was surprised that he’d referred to himself in that way. Since he doesn’t speak English, his words are at times misconstrued in translation, he explains. “However, yes, I must be fantasist. I always imagine character, thought and behaviour when I look at the internet and social media.”

As Takamatsu breathes surrealist life into his digital images, we can feel the fantasist world of his œuvre. It’s a place where eerie avatars take on a life of their own. But perhaps a more apt description for this artist is “metaphorist.” Using his singular vision and imagery, Takamatsu is able to explore questions of beauty, contemporary society and the digital world.