March 20, 2025

Japanese Wine: Chasing the Phantom Wine in Hokkaido

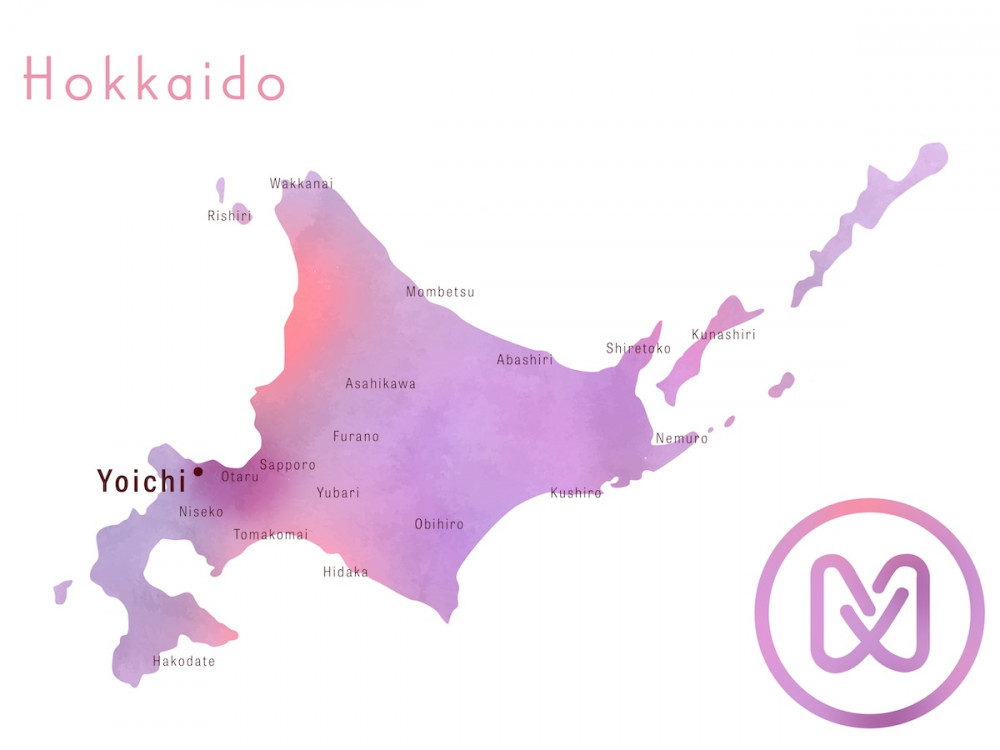

How Takahiko Soga has redefined Japanese winemaking in Yoichi

The rental car hums beneath us, tires crunching through Hokkaido’s snow. The road before us rolls out like a white ribbon, curving behind the distant mountains. In the pits of January, their peaks soften with a veil of snow. We wind through dusted hillsides on frosty roads, passing trellised vines lining back gardens. Inside the car, there plays no music. Our chatter has slowed to a stop so as not to disturb the silence.

This is Yoichi. I’m here chasing an obsession; after tasting one of the most elusive wines in the international market, I’ve been fantasizing about tasting it again ever since. Takahiko Soga’s ‘Nana Tsu Mori’ leads me to Japan’s northernmost island, and I’ve bagged myself an appointment with the Godfather of Yoichi himself. I’m here in Yoichi—ichi-go ichi-e—seeking the phantom wine.

Takahiko Soga meets me at the door of his cellar, sagacious and still against a sheet of white. Clambering through the snow towards him, I’m quickly conscious of my eagerness. He appears a man as mystical as the wines he makes, and I must be one of the million sommeliers and journalists, wide-eyed and bushy-tailed, dying for an introduction. “Your vines—they’re covered in snow,” I probe as we trudge up the slope of his famed ‘Nana Tsu Mori’ vineyard. “This amount of snow is good,” he replies with a kind seriousness. “It insulates the vines. This way they’ll survive the winter”.

He goes on to explain that, while in other wine-making regions, global warming has been crucial for achieving grape ripeness, a yearly increase in temperature could be devastating to his crop. Without a sufficient blanket, his beloved Pinot Noir won’t survive Yoichi’s harsh weather conditions. “Perhaps, then, we will plant something else”, he smiles.

It takes no expert to understand that vineyard management in Hokkaido is not for the faint of heart. With subzero winters thawing into sweltering summers, no sooner does the panic of frost resolve does the fear of rot set in. It takes patience to understand this unique region—to make wine there takes a miracle.

The Rise of Japanese Wine

Winemaking is not necessarily new to Japan. In fact, Japan’s relationship with wine dates back to the late 1400s, when high-class elites first tasted imported wine. By 1697, a Western-style winemaking method had already been published in Japanese. Records of large-scale vineyard planting date back to the 19th century, however, interest was slow and a climate unsympathetic to grape growing meant investment was apprehensive. It wasn’t until the 21st century that Japan even recognized Yamanashi as its first Geographical Indication for wine.

Nowadays, this is where most of Japan’s wine production still happens. Yoichi is more commonly associated with another beverage: whisky. Yoichi became synonymous with whisky production almost 100 years ago with the establishment of the Nikka Whisky Distillery in the 1930s, and will forever be the birth-site of the Japanese whisky revolution. However, when one of Soga’s Pinot’s wiggled into the wine list at Noma in Copenhagen, a new spotlight permanently cast itself over Hokkaido wine—and for good reason.

Soga’s entry into the world of wine began early, learning from his father, who runs Obusé Winery in Nagano. Dissatisfied with producing polished, man-made wines crafted as souvenirs for tourists, he turned to farm work instead and developed a sensitivity to nature that shapes his winemaking today. After a decade of learning viticulture with Californian mentor Bruce Gutlove at Coco Farm on Japan’s mainland, Soga was ready to put the skills he’d learned to use and start shaping his own path.

This was the early 2000s when the whole world began looking at low-intervention, sustainable farming and winemaking under a whole new lens—a movement we now know as ‘natural wine’. After attending a seminar on Biodynamics with the great Nicolas Joly, Soga was left at a point of no return. He made a commitment then to sustainable farming and has never looked back. When asking him about his choice now, over twenty years later, he seems as steadfast in his decision as ever. “When chemicals are put in wine, it loses its life,” he tells me gravely. “If I use too many sulfites, you can’t taste Yoichi”.

Taste Yoichi, Discover Umami

I’ve thought about that phrase quite a lot in the months since I first met Takahiko Soga. “Taste Yoichi”. The notion that place shapes wine is not a new one—like tasting the sea in a glass of Chablis and discovering that soil there is peppered with oyster shells.

Yoichi’s unique terroir is made up of a cool climate, a variety of microorganisms that provide critical microbial diversity, and, most importantly, a thick topsoil atop volcanic clay and Basalt. This forms from the cooling of volcanic lava—one of nature’s miracles. Soga claims the dirt of Yoichi is where the umami character in his wines comes from.

The key to understanding great Japanese wine is thinking about Japan’s gastronomic heritage. Pairing red wine with fish may seem like the cardinal sin, however, Soga swears that his wines are great with sushi and sashimi. He isn’t wrong—one of the greatest meals I ever ate was fugu alongside Nana Tsu Mori ‘16. What sets these wines apart from any other region is an inherent flavor profile that’s distinctly Japanese.

Fondly nicknamed “the phantom wine” for a tendency to appear on the market and then disappear almost as quickly, Nana Tsu Mori is the domaine’s flagship cuvee. However, there are some vintage-dependent wines in production, too. Nana Tsu Mori Blanc de Noir is a compelling white wine made using Botrytis-infected Pinot Noir (Noble Rot), fermented dry.

The result is an inimitable expression of jasmine tea, honey, mushroom and, of course, umami. Soga also works closely with neighboring growers of Yoichi to produce a Passetoutgrain—a juicy, thirst-quenching red made with Pinot Noir and negotiant Zweigelt. Clos da Descion is arguably Soga’s most elusive cuvee (even more elusive than his phantom Nana Tsu Mori). It’s 100% Pinot Noir from a plot who Keiichi Murakumi, Soga’s right hand man, farms. The result is an altogether different beast; darker, with firmer tannins and an incredible structure.

Soga’s approach is simple: do as little as possible. But, without man-made intervention, natural winemaking is about trial and error. Trust and hope. A vintage in life can be somewhat emotional; the devastation that frost can bring overnight, the anxiety that rot might wipe your crop.

Nevertheless, if you persevere this way, you have wines that entrench themselves in honesty—living proof of a place, a year. Nana Tsu Mori 2021 bottlings, for example, are brooding and ripe, telling the tale of the blistering summer. ‘22s are a world apart, bright and electric. Isn’t that more interesting than something that always tastes the same?

“Why whole cluster,” I ask, back inside the barn that Soga coins as a cellar. Of course, I thought I already knew. Whole cluster fermentation is the inclusion of grape stems in the fermentation process of winemaking. To destem or not destem is an age-old conversation still happening in Burgundy, the home of Pinot Noir, and I had a feeling that Soga’s choice would be one of style.

Soga chuckles. “I cannot convince a Japanese farmer to sit and remove the stems. It takes too long. So, everything goes in. If we have volunteers here for harvest and it starts raining, then we cannot pick, so we get them to destem instead.” I should have guessed. A philosophy embedded in simplicity, what other approach did I expect?

It’s Only Just Beginning

The endeavor for simplicity for Soga, however, has a deeper footing. He believes that the future of Yoichi is steeped in the growing community around him. Anybody should be able to make wine. The influence of his mentorship within the region is hard to ignore. Past apprentices are now all across Japan, forming some of the most exciting parts of the country’s winemaking community.

Atsushi Suzuki, whose winery is around the corner from Soga’s, is producing particularly expressive Zweigelt. He is following Soga’s template of organic farming and simple winemaking—with delicious results. His wines have gained somewhat of a cult following within Japan. Murmurs of their quality are already stirring up elsewhere.

Just up the road, Atsuo Yamanaka has made a home for his winery Domaine Mont after finishing two years of work with Soga in 2016. Inspired by a background in Japanese tea, he focuses on Pinot Gris. He finds the variety’s delicate flavor comparable to the country’s most beloved beverage.

He, too, continues Soga’s philosophy of simplicity and sustainability, with no additional sulfur. Soga doesn’t plan to stop there. He currently employs Japan’s first Master Sommelier, Toru Takamatsu, as his apprentice winemaker. Takamatsu already has big plans for his own future in Yoichi.

Driving away from Takahiko Soga’s cellar, I’m abuzz with excitement. I feel a weight of honor after having caught a glimpse of a region so on the threshold of something wonderful. In the past ten years, Japan has watched Yoichi grow from a little town with only two wineries to speak of to a living, breathing wine region boasting seventeen domains.

It feels as though, for Yoichi, this could just be the beginning. A region grounded in a fraternity, open to experimentation, and a willingness to etch out its own identity. Humble, simple, honest. Somehow extraordinary.

If you enjoyed this article about Japanese wine, you might also enjoy reading The 9 Best Japanese Whiskies for Gifting.