All of the articles in our Fresh Ink series highlight the English-language debuts of never-before translated works of prominent Japanese writers.

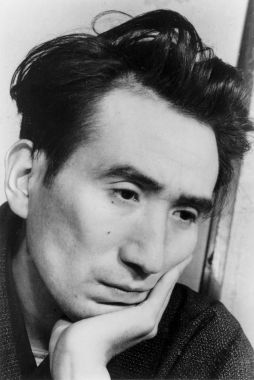

Osamu Dazai (1909-1948) is one of the best-known authors in Japanese literature, especially for his soul-crushingly depressing novels like “No Longer Human“ and “The Setting Sun.” Dazai had a troubled life and struggled to gain an audience. His writing is defined by relentless self-examination and constant estrangement.

“A, Autumn” is a remarkable, previously untranslated poetic short story about autumn, written in 1939 — years before his most famous novels. While on the surface, this story is no less depressing, it is actually alive with radical possibility. A reader gets a close-up look at Dazai’s poetic process, as feelings and thoughts about autumn inspire random, almost nonsense and wildly dark poetic riffs, on which Dazai then reflects and ruminates.

Dazai repeatedly states that he doesn’t understand the words he has written. Neither do I, because I vehemently disagree with his interpretation of autumn: I think fall is the most beautiful season. The quality of the sunlight, the crispness of the air, the radiant leaves, the way the world is relieved from the heavy, humid summer air. Within Dazai’s foreboding and seeming hatred for autumn, he reveals the way that subjectivity impacts language and accordingly, the way one views the world. Dazai recognizes that he is depressed, and his confusion about his own poetry tells a reader that he is not necessarily to be trusted. But anyone can see that his words hold shards of truth.

A season can inspire so much. These fragmented daydreams of autumn help us understand, criticize, and embrace the changing season, while challenging our own assumptions, freeing us to experience autumn anew. Without further ado, below is the first-ever English translation of A, Autumn.

A, Autumn

As a full-time poet, I always have subject material ready, because I never know when a commission is going to come.

If I get a commission for a poem about autumn, I think, here we go, and pull out my folder full of notes for the letter ‘A,’ flip past anger, appreciation, aqua and pick out the notes for ‘autumn.’ I settle down and read over my notes.

Dragonflies. Transparent, they read.

The words seem to suggest that while in autumn, dragonflies are sickly and dying, their spirit continues to zip and flutter around. They appear transparent in the fall sunshine.

Fall is summer’s leftover heat. Scorched earth.

Summer is a chandelier. Autumn is a stone lantern.

A shame, those cosmos.

Once, at a countryside shop while I was waiting for my chilled soba, I opened up an old magazine on the table. It had a photo of the 1923 earthquake. A flat, burnt plain, with a solitary woman squatting in a checkered yukata, exhausted, all alone. I loved that wretched woman so much that my chest nearly caught fire. I even felt fierce lust. Wretchedness and desire, two sides of the same coin. I could barely breathe. It was the same suffering I felt when I happened upon a field of withered cosmos. It instantly suffocated me, just as the dying morning glory had before.

Autumn comes at the same time as summer.

Deep within summer, autumn lies hidden, already on the way. Most people, fooled by the scorching heat, fail to notice. But if you hone your ears and listen, you’ll hear the buzzing insects, and if you watch the gardens closely, you’ll see fall bellflowers blooming at the dawn of summer. Even dragonflies are originally summer creatures, and the fall persimmon bear their fruit in summer.

Autumn is a cunning demon. It assembles its getup over the course of summer, crouching with a sneer. As a poet, I can pierce its disguise. I feel pity for all the families, delighting and celebrating with trips to the sea, or to the mountains. Autumn is already here, hidden within summer. Autumn is a deep-rooted menace.

A ghost story, all right. Anma massage. Hello.

Beckoning, silvergrass. And beneath, tombs.

Ask for directions, she goes mute, a withered field.

I don’t understand many of the things I’ve written. They’re supposed to be memos for my own reference, but I hardly understand them myself.

Outside my window, I see an ugly autumn butterfly swooping and flapping around the black soil of my garden. It clings to life with uncommon strength. It is not fleeting.

I was in a great deal of pain when I wrote those lines. I will never forget that moment. But I will not speak of it now.

A deserted sea.

Have you ever swam in the ocean in fall? Broken paper parasols wash onto the beach, the remains of pleasure. Discarded paper lanterns decorated with the Japanese flag, ornate hairpins, paper scraps, chipped records, milk bottles, silvergrass muddied with red, all pounding and thrashing ashore.

Ogata had children, didn’t he?

I love the way my skin gets dry in fall.

Airplanes are best in the autumn.

I don’t understand much of it at all. They seem to be fragments of autumn conversation that I overheard.

I also wrote this:

Artists were supposed to be allies of the weak.

They have nothing to do with autumn, these words I’ve written, but perhaps you could call them seasonal concepts.

And this:

Farms. A picture book. Autumn and soldiers. Fall silkworm. A fire. Fumes. A temple.

Just look at the mess that I’ve written.

For more on translation, also check out:

‘Tales of the Zashiki Children’ by Kenji Miyazawa

Previously untranslated short stories by the prolific Japanese writer

How the English Language Failed Banana Yoshimoto

Looking back at the Japanese literary icon 30 years after the translation of her debut novel ‘Kitchen’

‘May Morning Flowers’ and ‘A Crooked Posture’

Introducing two of Kanoko Okamoto’s never-before translated works