December 18, 2020

Fresh Ink: ‘Tales of the Zashiki Children’ by Kenji Miyazawa

The English-language debut of a prolific Japanese writer

ALL OF THE ARTICLES IN OUR FRESH INK SERIES HIGHLIGHT THE ENGLISH-LANGUAGE DEBUTS OF NEVER-BEFORE TRANSLATED WORKS OF PROMINENT JAPANESE WRITERS.

Kenji Miyazawa was a writer of fairy tales in the sense that mystery and magic infused almost all of his writing. As a whole though, the label “fairy tale” does not quite capture his work: his whimsical, fantastic and scary children’s stories fall in a unique position among the worlds of children’s literature, fable and fairy tale. Sometimes, there are clear morals. Sometimes, there are not. At times, he waxes lyrical and poetic. Other times, he describes straightforward mishaps and misunderstandings. And despite how grounded Miyazawa was in the settings and lore of northern Japan, his stories also transcend the label of being “local” or “Japanese.”

His most famous work, the near-untranslatable “Night on the Galactic Railroad,” is mature enough to explore feelings of loss, abandonment and even cruelty. This faith in children expands to his broader catalogue of children’s work: while they are children’s stories, he does not shy away from big and even dark themes.

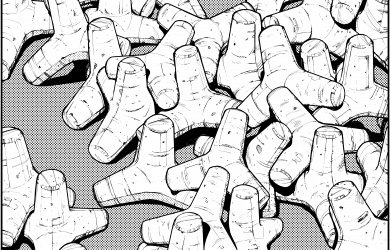

MIYAZAWA’S UNTRANSLATED 1926 work “Zashiki Bokko no Hanashi” (Tales of the Zashiki Children) is a collection of short vignettes that spin local lore about zashiki warashi, or “guest room children,” into a precise, unnerving series of incidents. Zashiki warashi are yokai (spirits) that live in the extra tatami rooms in old houses, and are said to perform pranks and bring good fortune to the families they live with. While zashiki bokko are in general a good omen, Miyazawa captures something eerie and almost divine about them: they are spirits that reject the labels of good or bad, and merely exist on their own accord. The spirits walk among us.

Here are a few local tales of the zashiki children.

One autumn day, when all the villagers went out to work in the mountain, two children stayed at home and played in the garden. No one was in the large house, and both house and garden were cloaked in silence.

But somewhere in one of the house’s zashiki, or tatami sitting rooms, the sound of a broom rustled and swished.

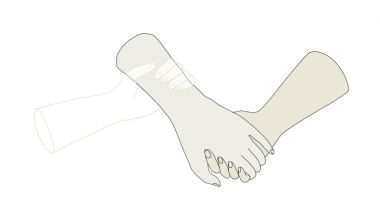

The two children grasped each other’s hands and crept across the house into the zashiki, but they found no one. The zashiki’s chests and drawers sat undisturbed, and the hedge around the fence was beginning to lose its green. The children didn’t see a soul.

Then they heard it again: the rustling and scraping of a broom.

Was it the call of a shrike? The rushing water of a distant river? A farmer gathering beans in a basket? Considering every possible option, the children listened to the swishing in silence, and realized that none of them matched the sound that they were hearing.

They knew they could hear it: the scraping and scratching of a broom, somewhere in the house.

Once more, the children tiptoed nervously towards each of the zashiki and peeked inside, but the rooms were empty. There was only the beaming sun that doused each room in light.

These are the tales of the zashiki children.

❝

“Ring around the rosy, pockets full of posy…”

Bursting with enthusiasm, exactly ten children held hands as they shouted out the song, swinging round and round and round and round the zashiki. Each of the children lost themselves in the joy of the game as they circled and spun.

Round and round and around and around, they laughed and danced across the room.

Then, somehow, there were eleven.

Each child still knew the faces of the other ten, and none of them had the same face as any other. And yet, undoubtedly, their number had increased by one. An adult appeared in the doorway and cried out, It’s a zashiki child!

But no one knew who the zashiki child was. They all sat down politely, each of the children insisting with wide eyes that they were not the zashiki child.

These are the tales of the zashiki children.

❞

Here is another tale of the zashiki children.

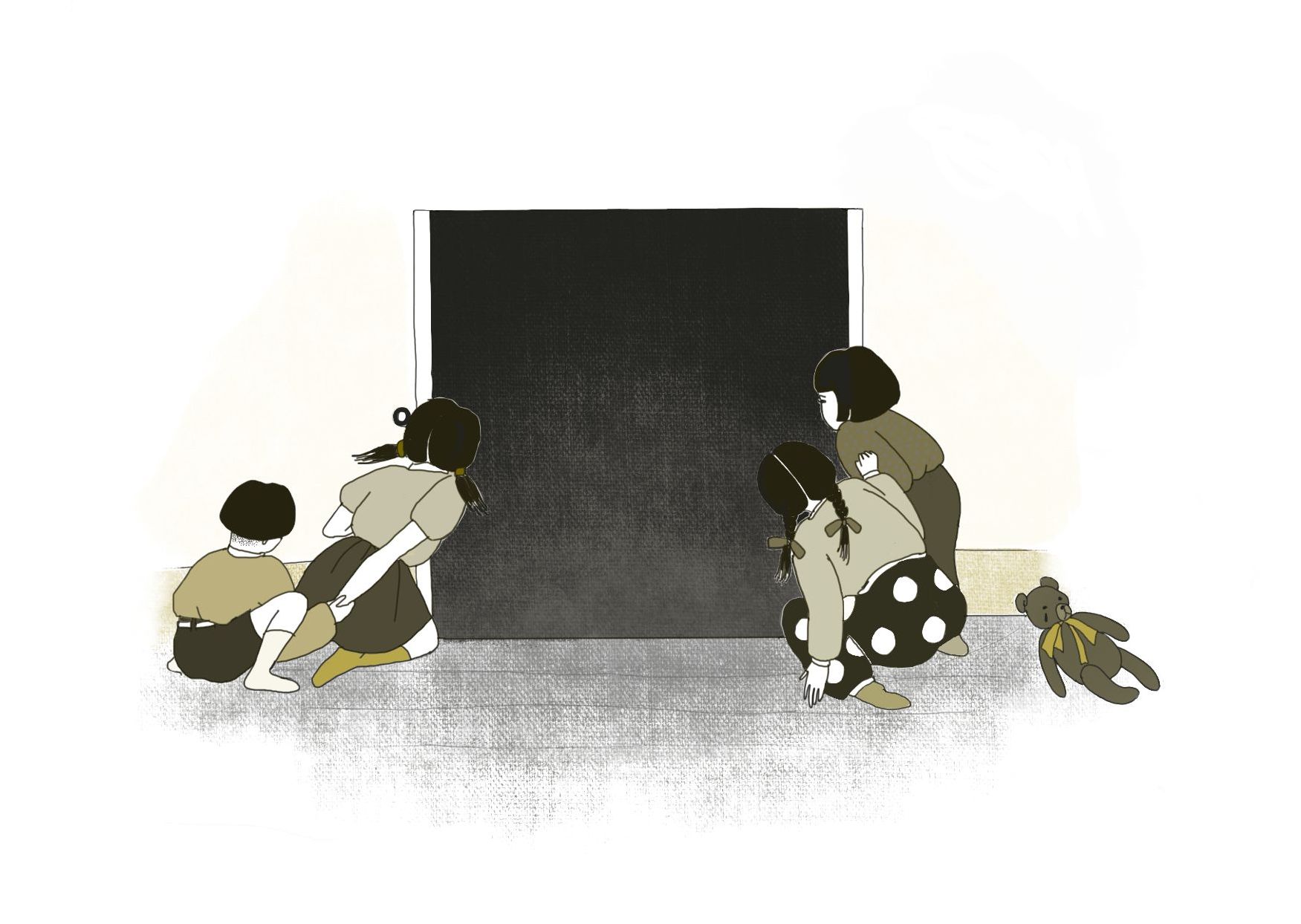

In the large house of a large family, in the middle of every autumn, the children gathered at the festival of Nyorai, the Buddha of scriptures. But this year, one of the children fell sick with measles before the festival.

He would cry out night after night in his sleep, “I want to go to Nyorai-sama’s festival. I want to go to Nyorai-sama’s festival.”

“We’ve pushed back the festival,” his grandmother told him kindly, patting him on the head at one of her visits. “Just get better soon.”

The month after the festival, he finally got better. The whole family gathered together. But the other children, who had their festivities delayed and had their toys taken as get-well gifts for the boy, felt like they had been robbed.

“Look what they did to us because of him,” they told each other. “Even if he comes, let’s not play with him, no matter what.” And the children promised each other they wouldn’t play with the boy.

The children were gathered and playing in the zashiki, when one of the children suddenly shouted: “He’s coming! He’s coming!”

“Quickly! Let’s hide!” The children ran out of the room down the hall into the smaller zashiki.

But right before their eyes, the boy who should have recovered from measles was already sitting cross-legged in the middle of the smaller zashiki, stuffed bear in hand, ghastly pale, rail-thin, face scrunched up and swollen with tears.

“It’s a zashiki boy!” everyone shouted, sprinting out of the house as fast as they could. They could all hear the sobs of the boy coming from inside the house.

These are the tales of the zashiki children.

❝

She sat still as a stone,

with her hands in her lap,

staring up at the night sky.

One day, the ferryman, who works at the gorge in the Kitakami River, told me what happened to him.

“On a night in mid-autumn not long ago, I had some sake and went to bed early. But then I heard someone calling out from across the river, “Helloo, helloo.” I got up and left my shack, and saw that the moon had risen to its peak in the sky. I hurried to ready a boat, and when I went across to the far shore, I saw a young girl wearing a beautiful hakama, decorated with a family crest and a sword in her belt. She was wearing sandals with white straps. I asked her if she wanted to cross the river, and she said she did. When we got to the middle of the gorge and she wasn’t looking, I took a careful look at the girl. She sat still as a stone, with her hands in her lap, staring up at the night sky.

“When I asked her where she came from and where she was going, she answered in a sweet voice, saying she had lived with the Sasada for a long time, but got sick of it and wanted to find someplace new. I asked her why she got sick of it, but she only laughed, and fell silent. I asked her again where she was going, and she told me she was going to Saraki Saito’s house. When we got to the shore, I went to help her off the boat, but she was gone. I sat down in my shack’s doorway, thinking that maybe it was all a dream. But I’m sure it actually happened. Because after that, the Sasada family fell to ruin, and Saraki Saito recovered from his illness, his daughter graduated university, and his family went on to become wealthy and powerful.”

These are the tales of the zashiki children.

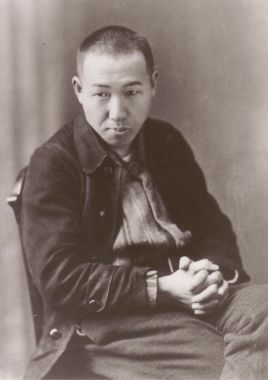

Kenji Miyazawa (1896 – 1933) was a Japanese poet and author of children’s literature whose major works include “Night of the Galactic Road.” He was also known as an agricultural science teacher and cellist who committed to Nichiren Buddhism after reading the Lotus Sutra. Miyazawa died of pneumonia.

Introduction and translation by Eric Margolis

Illustrations by Monique Miller

Love Japanese literature? Also check out:

- Kanij Hanawa: Scientific Literature About an Unscientific World

- Yukio Mishima: The Resurgence of a Japanese Literary Master

- Mind the Gap: The Ongoing Battle to Translate Japan’s Leading Literary Women

- Across Space & Time: Translating ‘Night on the Galactic Railroad’