The Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo is normally a quiet and sparsely attended venue. This is because of the Japanese public’s tepid interest in most modern art, and the venue’s relative distance from a convenient rail or subway station.

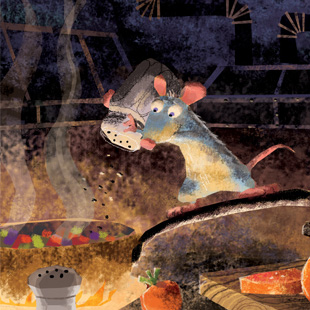

But it’s a different story right now, thanks to the present exhibition “Pixar: 30 Years of Animation,” which looks back over the history of the trailblazing computerized animation company behind such hits as Finding Nemo, Toy Story, Monsters, Inc., Cars, Ratatouille, Wall-E, and others. Instead of quietly echoing galleries, there is now a bit of a bustle about the place, with fans of animation thronging the show to find out the secret of Pixar’s success.

Of course, there are two elements to this: the medium and the message. Starting as Graphics Group, a section of the computer division of Lucasfilm, before launching as a separate company in 1986 with Steve Jobs as its majority shareholder, Pixar was the first big effort to capitalize on the possibilities of computers to generate increasingly lifelike imagery. It’s now part of The Walt Disney Company.

For those interested in the technical side, there is much here. In particular, there’s a very effective video—featuring Lotso Bear from Toy Story 3—that shows how a scene changes with each computer animation treatment, as first the crude movements are mapped out, after which they are refined, down to each hair on the bear’s fur being controlled by its own equation. Mind-boggling, but all possible thanks to the enormous advances in computer technology during the lifetime of the company!

One of the criticisms made of computer animation is that it lacks the human touch, as if an army of CGI programmers slaving away over oodles of code is somehow inhuman. Well, maybe just a little.

To refute such an impression, the show does much to show the more analogue inputs of the creative process. This isn’t too hard to do because, before things get too technical, the creative process is not dissimilar to the way the old Disney Company got projects started back in its golden age, with actual sketches and studies of the characters and the settings.

The exhibition features plenty of this conceptual artwork, allowing us to see that the original Buzz Lightyear character from Toy Story was originally envisioned as a much pudgier character rather than the more “macho” figure with which we are now all familiar.

The exhibition also features lots of urethane resin models of the various characters, showing the final agreed form. These are used as reference works by the animators to resolve any issues, and, in a sense, these are the souls of the characters.

The exhibition’s highlight is the Zoetrope, or “Wheel of Life.” This is a complex three-dimensional merry-go-round, featuring characters from Toy Story in various poses. When it spins at high speed and under strobe lights, the various poses of the characters blend together to give the illusion of movement, while the wheel itself seems to be stationary—an uncanny anime version of the philosophical concept of the “unmoved mover.”

Whatever the medium of art—computer graphics or hand-drawn—the message is still key. The models, drawings, and visual installations on show here demonstrate that it is raw imaginary input, along with constant informed feedback, that has been the driving force behind Pixar’s success.

Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. Until May 29. http://j.mp/pixar30years