September 14, 2018

Revelations of a Hafu

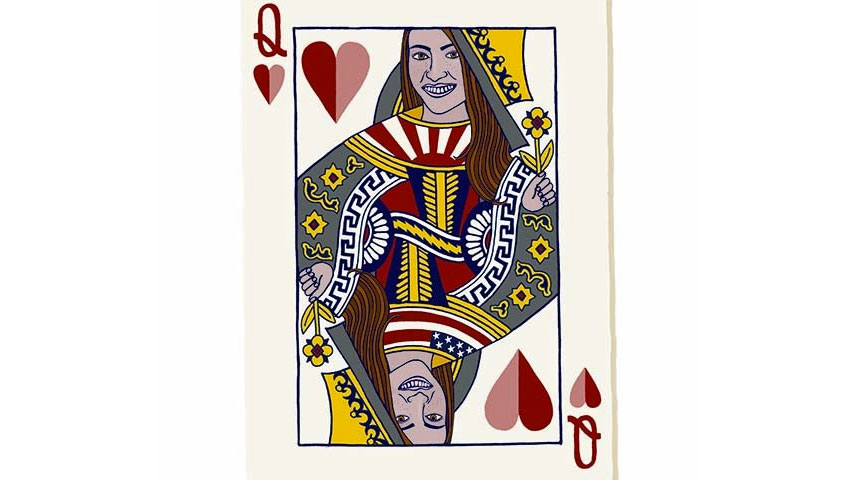

The best of both worlds comes with perplexing consequences

By Grace Harrah

As a child, there are a few questions that I quickly learned I would have to answer for the rest of my life.

“So which do you prefer, Japan or America?” “What do you identify more as?” “What language do you dream in?”

These simple yet ambiguous questions of identity have puzzled me since my earliest memories. The Japanese word for people like myself, “ha-fu”, literally translating to half, represents the biracial Japanese population that grow up in a hazy world of confusion; unaware of their true identity amid feelings of displacement in Japan. The truth is, us hafu are constantly misrepresented as something we are not. And quite frankly, I’ve also constantly asked myself the question: “where do I fit in?”

My dilemma began while attending a Japanese elementary school, when I had yet to learn English. Teachers, strangers and even friends would look at me as if I was a foreign exchange student when, in fact, I had never been out of the country. To my younger self I was fully Japanese, but to the outside world I was a foreigner—people were often amazed that I could speak the language so well. A cultural barrier was established from then on, setting me down in a world of confusion and discombobulation, having to face the constant feeling of being out of place. Especially in Japan, a repetition of the same alienating experiences led me to feel misunderstood by the society to which I belonged and in a place that felt like home. Not to my surprise, when I first lived in America in order to learn English, the same dilemma presented itself. They only saw me as a non-American from a far away place. Eventually the experiences contributed to a limited understanding of my identity and belonging, that I was never truly “home” because there is no magical country where only hafus exist. At least once in their life a hafu has felt out of place in the one space everyone deserves to feel comfortable and safe: home.

Though the differences you face as a hafu in Japan are often challenging in a personal sense, in recent years the media has popularized the term, with an expanding number of celebrities and models recognized as hafus. The idolization of hafu in Japan is quite particular to a certain type of hafu: those that are Caucasian-Japanese mix are featured in the media frequently than any other ethnic mix. Although the admiration for hafu is a widespread sentiment in Japan, there is a notion that white-Japanese mix are the quintessential hafu, which is a deceptive facade cast on the community and a misrepresentation for those hafu mixed with other ethnicities. In 2015 Ariana Miyamoto, who is half African-American, was criticised for winning the Miss Universe Japan Pageant. People were outraged, using twitter as an outlet to disapprove of her mixed-race heritage and claiming that she does not have the authentic Japanese appearance to properly represent the country. She received comments targeting her achievement such as, “Even though she’s Miss Universe Japan, her face is foreign no matter how you look at it!” and “Is it ok to choose a hafu to represent Japan? Sometimes the criteria which they use to select Miss Universe is a bit of a mystery.”

In 2018, the World Population Review summed up the percentage of the Japanese population considered “ethnic” at 98.5 percent, a very high number in the context of our increasingly globalized world. The experiences of the various hafu mixes and backgrounds may be different, but I am certain each hafu’s story includes the hardships of being biracial in a purportedly homogenous country. In a country where conformity is a way of life, being distinctly against the norm can feel lonesome and alienating—an outcast in the place you call home.

Admittingly, it is relieving when I meet others like myself in Japan. It comes with an instant connection and a mutual understanding, as if we’ve shared the same childhood. All it takes is “oh you’re a hafu, too?” to skip introductions and flood them with questions examining the similarities and differences between their experiences and mine.

If I had another option when I was growing up—perhaps a place where all of my friends were hafus and no one asked where I am from, or what I am, or what I identify more as; where others would not be in shock that I was speaking the only language I knew and I wouldn’t be questioned for my unique features—my identity crisis at age eight could have been avoided. Unfortunately, such wonder-hafu-land does not exist and I have to deal with who I am, as a Japanese-American, hafu, whatever the society wants to label it.

Years have passed since my first acknowledgement of being a hafu in Japan, though the questions I get asked have not changed since then. Yet it still captivates me, and is a rather entertaining sight, when others react to my answers. Seeing, hearing and experiencing Japan as a hafu is a uniquely eye-opening and fascinating experience. While it is difficult, not having an exact place where I belong is a world on its own filled with trials, expeditions and various answers that I have yet to uncover.