March 7, 2017

Rogue Ichi

How the “Japanese James Bond” inspired Star Wars’ breakout character

Star Wars is no stranger to borrowing from Japanese culture, from Darth Vader’s attire clearly being based on samurai armor to the katana-esque lightsabers. But the borrowing actually goes further than that. The idea of telling large chunks of the story from the perspective of two bumbling comic reliefs, C-3PO and R2D2? That was inspired by the 1958 Akira Kurosawa film The Hidden Fortress (Kakushi toride no san akunin), which might also have had a hand in helping shape the character of Princess Leia.

In short, if it wasn’t for Japanese culture, there would be no Star Wars as we know it today and, therefore, no Rogue One or Donnie Yen’s breakout side character Chirrut Îmwe. And what a horrible world that would be!

In the newest movie, Chirrut is a blind warrior-monk who joins a group of rebels trying to steal plans for the Death Star. Much like Boba Fett, the bounty hunter from the original trilogy, Chirrut doesn’t have a whole lot of screen time in Rogue One, but the little we see of him was enough for most people to rank Chirrut as one of the greatest Star Wars characters ever.

And you really have to wonder if the character’s popularity isn’t somehow related to him also being influenced by Japanese culture.

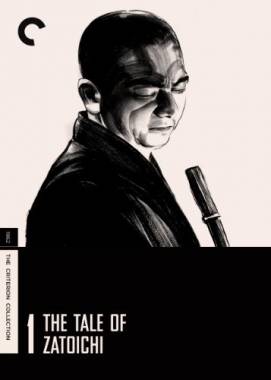

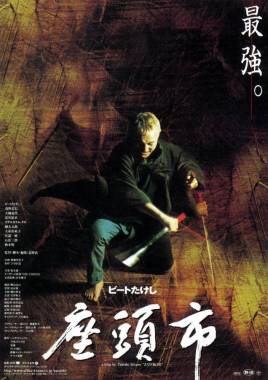

Although no one in their right mind could call Chirrut a “rip-off,” the character has obviously taken some cues from Zatoichi, the eponymous character of the Zatoichi film series, whom some call the “Japanese James Bond.” (Not to be confused with You Only Live Twice, the 1967 Bond movie which tried to convince us that Sean Connery in yellowface could pass for a Japanese person.)

Zatoichi earned his unofficial nickname due to being portrayed by different actors in a long-running series of movies that stretches all the way back to 1962. That’s when moviegoers were first introduced to the master swordsman who wanders the land helping people… despite being completely blind. In fact, Chirrut’s introductory fight scene is extremely similar to the action in most Zatoichi movies, with their enemies first paying them little attention because of the characters’ lack of sight, and then suddenly eating more dirt than an industrial excavator.

Both Chirrut and Zatoichi rely on their other senses sharpened to near superhuman levels to dispose of their foes with relative ease. And although Zatoichi’s weapon of choice is usually the sword cane, he does briefly exchange it for a bo staff in Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo (1970), which bears a striking resemblance to Chirrut’s weapon of choice. But that’s not all.

Zatoichi is usually portrayed as a hinin, which was an outcast class in 17th to 19th century Japan that literally translates to “non-human.” Similarly, in Rogue One, Chirrut used to be a Guardian of the Whills, a religious order that worshipped the Force, whose members were reduced to the lowest levels of society under Imperial rule. In fact, when we’re first introduced to Chirrut in Rogue One, it’s when he’s begging on Jedha. But, much like Zatoichi, he doesn’t seem to mind his low social standing. Both characters’ decisions to help those in need don’t stem from some kind of resentment towards a world that unjustly made them into outcasts. They only engage in combat due to a series of happenstances. They never seek out trouble. Trouble just has a nasty habit of finding them all on its own.

There are of course differences between the characters. For one, Zatoichi firmly believes that because he has killed so many people, he is a bad person beyond redemption. Chirrut, on the other hand, sees himself as a servant of the Force, so everything he does in the service of his faith is justified in—for lack of a better word—his eyes. But all the other similarities between him and Zatoichi cannot be ignored. It’s obvious that the Star Wars warrior-monk owes a lot to the Japanese James Bond, but Donnie Yen thankfully then took that inspiration and did something really spectacular with it…Unlike Rutger Hauer in the 1989 Zatoichi-inspired movie Blind Fury, about which the less said, the better.