February 14, 2020

Speaking the Emperor’s English

A brief history of the royal family’s foreign language skills

When it comes to Japanese, it’s hard to find a group of more eloquent speakers than the imperial family of Japan.

The imperial family’s consistently high level of proficiency in the national language can differ so much from the average citizen, that normal Japanese people can’t understand their own emperor’s words.

This was true post-World War II, as Emperor Showa’s voice was heard for the first time over a recorded announcement to his people that was so formal and intricate, that many needed interpretations. Even Emperor Emeritus Akihito’s recent formal televised announcement of his resignation was seen as a bit over the heads of average Japanese speakers. So, it’s safe to say that the Japanese linguistic ability of the imperial family is good; perhaps even too good at times, for practical communication.

But what about the Japanese royalty’s forays into the more foreign languages that lurk outside the castle walls? Much ink has been spilled remarking on the fact that Emperor Naruhito is the first on the Japanese throne to speak English openly and fluently. But he’s not the first royal to receive a foreign language education.

From Meiji’s first German class in his Tokyo castle, to Naruhito’s study abroad at England’s most prestigious school, the imperial family has repeatedly rebuked the silence and reclusiveness of the sakoku era.

The last emperor to live and reign over Japan’s sakoku (closed country) era was Emperor Komei, who dressed his entire life in the traditional imperial wardrobe, ate traditional Japanese food and spent his days writing traditional Japanese poetry. He was adamantly against the Westernization of Japan, and it’s speculated that he never met a foreigner in any meaningful capacity throughout his entire life. He was the last Japanese emperor to die without at least a brush with foreign language. Emperor Meiji, his son, despite never once leaving the island of Japan, made a valiant effort within his lifetime to learn or at least get a working grasp on foreign conversation.

Disastrous encounters

At the time of Meiji’s education, English was far from the most important language to the Japanese. Most of the new Meiji-era nobility instead found German or French to be the most romantic and exotic tongues to practice. The Meiji-era court and nobility system was shifted to better emulate the Western-style monarchies of Europe. This meant knowledge of a European language carried quite a bit of social capital.

Meiji was instructed in German from a young age by his tutor, Kido Takayoshi. The reformers of the Japanese government intended to craft him into the first ruler of their new, modern Japan. However, it was a long and difficult road. His first-ever encounter with a foreigner of any kind, a British diplomat in 1868, was close to disastrous. Dressed in the old-school imperial dress of a Shinto priest, and even speaking in his own native Japanese, Meiji was perhaps intimidated. He uncharacteristically stumbled over his words and lost his place on the page.

A year later, Meiji met with Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh. He was the first member of foreign royalty to ever have a presence with the emperor; a German. This audience went far better, solidifying a tradition of friendship between the German and Japanese royal families.

A potent language learner

Emperor Taisho was the sickly and oft-forgotten son of Emperor Meiji. Taisho had no aptitude for math or science. Perpetually in poor health and often accused of having a mental disability, he did quite poorly in school and was pulled out of the imperial classroom by middle school. One area that Taisho did show promise was foreign studies. He excelled in history and took a keen interest in Chinese and French. French particularly amused him, and he often found himself tossing bits and pieces of the language into his daily Japanese.

This tendency to synthesize and rapidly switch between French and Japanese annoyed Meiji greatly, who found it unbecoming for a Japanese prince. Perhaps this annoyance was simply because of his son’s clear advantage in language retention. While often written of as an ineffective and weak ruler, perhaps this is an area where historians should give more ground to Taisho. In comparison to both his father and his son to be, he proved to be an unusually energetic and potent language learner.

Emperor Showa, often referred to by his personal name of Hirohito in the West, was the son of Taisho, who passed away young at the age of 47. While not much is written about his foreign language education, Hirohito was even better educated than his father and grandfather.

Studying abroad

It is likely that Hirohito studied a bit of two or three foreign languages. Likely Chinese and French or German. Later in his life he would have ample exposure to English, but not much is known about whether he took any formal classes. Hirohito was the first emperor to have actively traveled out of the country. He took a six-month long trip to tour the nations of Europe as a young prince. This trip was an opportunity for the future ruler to practice his foreign introductions and make connections with the heads of state and royal families.

However, Hirohito never seemed to feel comfortable in his abilities, and relied on a translator for all non-Japanese conversations, including postwar discussions with the American occupying leaders. Even if he wasn’t a good student of foreign language himself, Hirohito clearly understood the value in it by the time the war ended. He wanted his own son to be well equipped.

The current Emperor Emeritus, Akihito, has perhaps the most carefully recorded and widely studied childhood experiences with foreign language studies. After the war, Hirohito stated that he would like his son to be properly educated and tutored in English. Whether this was for practical, diplomatic reasons in the face of the ongoing occupation, or if this was a symbolic gesture of goodwill to the former enemies of Japan is not clear, but Hirohito was serious in this commitment.

Prince “Jimmy”

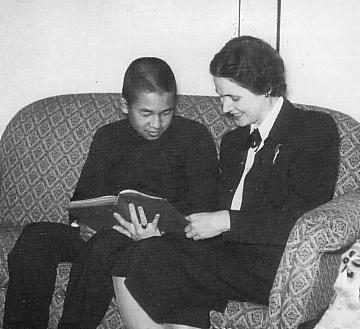

The Imperial Household collaborated with the American Occupying Forces to find a suitable teacher from the U.S. for the elementary school-aged prince. The commission appointed Elizabeth Vining from the University of North Carolina as Prince Akihito’s official foreign language educator. As his English teacher, she was adamant not to cave into Japanese expectations of how to treat a young crown prince.

Vining taught Akihito in a small classroom setting with the children of Japan’s former noble families as his classmates. Vining assigned Akihito the name “Jimmy.” When the small heir to the throne objected and said that he wanted to be called “prince,” Vining informed that unfortunately, in her class, his nickname would have to be Jimmy. “Jimmy” was taught Western manners in English, as Vining didn’t know the first thing about Japan. She arranged for local Tokyo boys of the same age from Western countries to come and hang out with the prince, and even began tutoring Hirohito and his empress on the side.

Akihito would remain friends with Vining for the rest of her life, visiting her at her Pennsylvania home and calling her on the phone. It’s hard to say how much this English education stuck with Emperor Emeritus Akihito. As a monarch, he was a shy one. As emperor, Akihito did not make his major public speeches in any language other than Japanese, and did not translate his own works. Finally, as a retired emperor, he’s foregone the spotlight almost completely.

The modern inheritor

Whether or not Akihito’s English skills persisted into adulthood and his silver years is not quite as important as the fact that the Western education clearly had a profound effect on him.

It was perhaps this love for his American English teacher and nostalgia for her classes that encouraged Akihito in the Western education of his own son, the former Prince Naruhito.

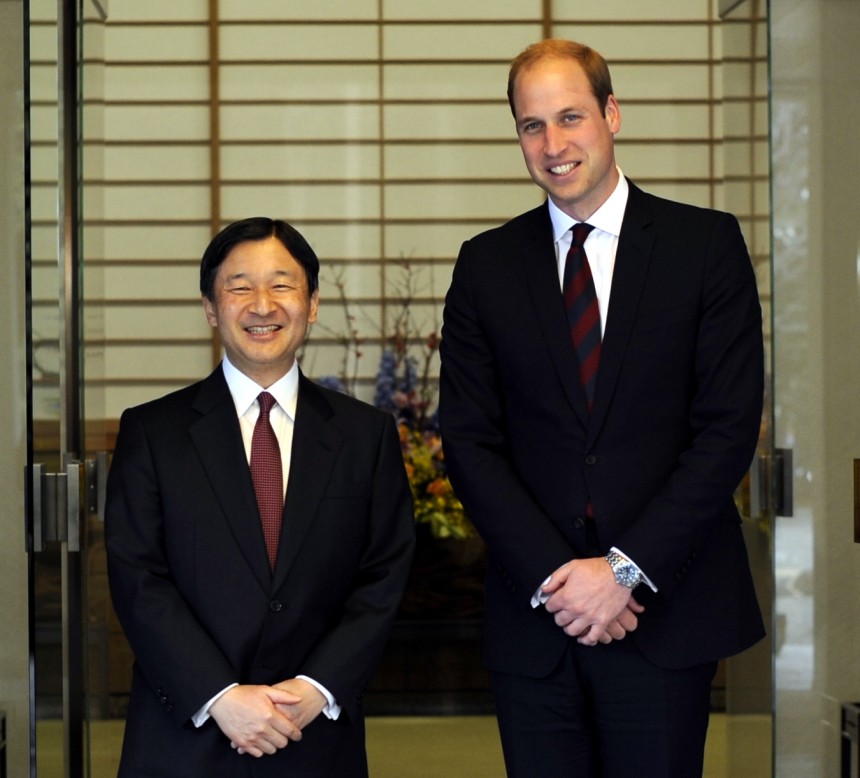

As a prince, Naruhito attended the prestigious University of Oxford. Due to this experience abroad, Emperor Naruhito was and still is completely fluent in English. His high level of study has given him the means through which to become not just workably-fluent in day-to-day matters but professionally and academically native-level. When meeting with the Queen of England herself, Naruhito did not rely on any translation, talking to her about art and history in front of the camera and in his own words, a sight that would have made the jaws of his ancestors drop to the floor.

One wonders, looking back, what the emperors of old would think. The modern inheritor of their bloodline speaks effortlessly and with dignity in foreign tongues, hopping across the world to meet with leaders near and far. From Meiji’s first German class in his Tokyo castle, to Naruhito’s study abroad at England’s most prestigious school, the imperial family has repeatedly rebuked the silence and reclusiveness of the sakoku era and sought to connect with the rulers and citizens of both their own country and abroad.

And it appears that Emperor Naruhito is the impressive final product of this century-long commitment.