While dining at a French restaurant one evening in the late 1980s, Israeli filmmaker Menahem Golan was surprised when his waiter, an out-of-work actor who recognized him, made the audacious decision to kick his foot high above Golan’s head while holding two bowls of soup. The soup remained in their containers, but the actor, a Belgian martial artist named Jean-Claude Van Damme, landed himself a meeting at the filmmaker’s production studio. That fruitful meeting led to the actor’s first break in Hollywood.

Van Damme was among a roster of 1980s actors who owe their careers to the independent production studio Cannon Films, and the legendary Israeli cousins Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, who transformed the studio into one of the most influential in Hollywood. Cannon produced over 300 movies, many of them B-pictures with the likes of Van Damme, Chuck Norris, Sylvester Stallone, and Charles Bronson. At its height, Cannon controlled around 20 percent of the U.S. box-office, but closed in financial ruin in 1994.

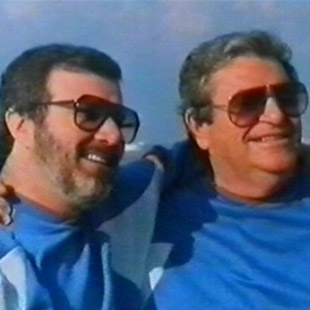

Golan and Globus are the subject of The Go-Go Boys: The Inside Story of Cannon Films, a documentary by the Israeli filmmaker Hilla Medalia that looks at the turbulent rise and fall of the iconic studio, and the two cousins who changed the way Hollywood looks at film production.

“Go-Go Boys” is the half-affectionate nickname for Golan and Globus, emanated from the cousins’ legendary high-turnover approach, with Golan producing or behind the camera while Globus took care of the money.

“They never stopped,” says Medalia. “In many ways, their focus was on making films—and making a lot of films. And I think obviously, in many ways, it was their success but also it was at one point what hung them.”

After producing a series of hits in Israel—including the hugely popular Lemon Popsicle (1978), the cousins moved to Los Angeles and purchased the struggling Cannon for $500,000. Within a few years, the studio was churning out almost 50 films a year. They would regularly shoot and release a picture within a few months, many of them fast-paced actioners like Missing in Action (1984) and The Delta Force (1986), as well as some high-end films like the Andrey Konchalovskiy classic Runaway Train (1985) and John Cassavetes’ Love Streams (1984). In addition, the studio also produced an endless array of flops, including the wonky effects-driven superhero disaster, Superman IV: The Quest for Peace (1987).

By the mid-’80s, Cannon was synonymous for ubiquitous, high-turnover blockbusters. Even in Japan, which warmly embraced the ninja genre with Enter the Ninja (1981), Cannon films endure today as nostalgic classics.

“It’s amazing that so many people in Japan like their films. It shows you [Cannon’s] reach: that their films got really everywhere around the world,” states Medalia, who was recently in Tokyo for the premier of her documentary.

This high-turnover approach left a bitter taste for some, and many people considered Cannon’s pictures “schlock films.” Hosts Gene Siskle and Roger Ebert of the popular 1980s film review show At the Movies called Golan and Globus “dealmakers.” Even Golan—who died shortly after The Go-Go Boys premiered at Cannes in 2014—admitted in the documentary that he would feel like a criminal spending $30 million on one film, preferring to make 30 films instead.

While this approach to filmmaking was rare for its time, what was even rarer was the faith that Golan and Globus placed in Hollywood. According to Medalia, the cousins would often codify projects with a simple shake of the hand, at times going on pure instinct.

Some of the time, this paid off for Cannon. When director Barbet Schroeder threatened to cut off his fingers if they didn’t give him work, Golan took a chance and gave the director what became one of Cannon’s signature art-house films, the acclaimed Barfly (1987). “Menahem had a big heart beyond his craziness,” Medalia recalls.

At its core, the story of Cannon Films is a tale of two cousins: the incomparably boisterous presence of Golan, mixed with the innovative business-savvy of Globus, and the synergy that’s essential for filmmaking to exist.

In the end, says Medalia, the Cannon story is about what we learn “from taking risks to following your beliefs,” and, ultimately, the “personal human story of wanting to make it, and failing, and crashing.”

The Go-Go Boys: The Inside Story of Cannon Films will play until Nov 27 at the Shinjuku Cinem@rt. In English and Hebrew (Japanese subtitles). (89 min)