July 31, 2020

The Resurgence of a Japanese Literary Master

Fifty years after his death, Yukio Mishima is reemerging in translation

Yukio Mishima may have gone out in an inglorious blaze in 1970, but three of his previously untranslated works have been released in the English-speaking world in the last two years, with another on the way.

To recap the scene: Mishima, then the leader of the nationalist, unarmed civilian militia Tate no Kai, entered a military garrison in central Tokyo on November 25, 1970. After taking an officer captive and failing to inspire the gathered soldiers to overturn Japan’s constitution and restore the emperor to power — quite the opposite, the soldiers laughed and jeered at him — Mishima committed seppuku.

It was another failure. The ritual act of suicide, committed by samurai warriors, involves plunging a short sword into the stomach and slicing from left to right, opening the belly. When the samurai finished, an assistant would decapitate him in a single blow. Mishima didn’t manage to open his stomach cleanly, and his assistant, hands trembling, couldn’t chop off Mishima’s head in one swing, either.

In many ways, you can identify a Mishima at first glance: tortured narcissists obsessed with beauty and fantasies of violence. But new translations are finally exposing Western readers to the true breadth and depth of Mishima’s work.

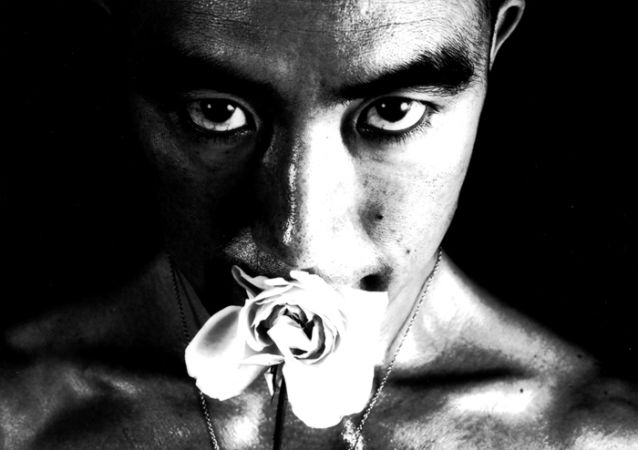

The narrative of Mishima’s life and death has often superseded his work owing to his far right-wing politics persists, as well as interest in his sexuality and status as a gay author. Mishima’s carefully cultivated image — a vigorous martial artist, his commitment to bushido, the code of the samurai and his fixation with masculinity, beauty and glory — has remained more notable than a lot of his writing. He even went to great pains to craft an image for an American audience with English-language interviews in the 1960s.

However, the contemporary resurgence of Mishima translations is starting to get readers back to the actual work. Which, incidentally, is very good indeed.

On the surface, Mishima is a writer of capital-L literary fiction, with dense works and elaborate language, in dense conversation with early 20th century European literature and theories of modernization. In many ways, you can identify a Mishima at first glance: tortured narcissists obsessed with beauty and fantasies of violence. But new translations are finally exposing Western readers to the true breadth and depth of Mishima’s work. There’s agony and beauty, but whimsy and variety as well.

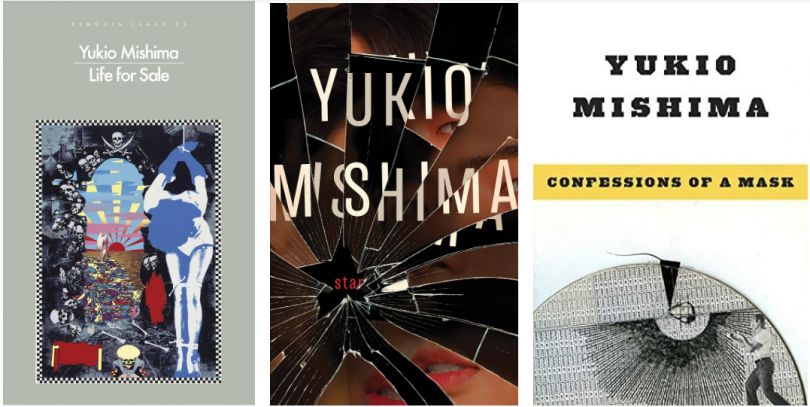

“This is a good time to expand our understanding of what Mishima was about,” says Stephen Dodd, translator of Mishima’s “Life For Sale” (2019) and the upcoming “Beautiful Star,” a rare Mishima science fiction novel. “’Life For Sale” is very funny, very kitsch, trashy, sexy. All these light, trivial, frivolous things make it a great read. But there’s another side to it, the more recognizable Mishima side — a deep loneliness and bleakness at its heart.”

In “Life For Sale,” salaryman Hanio Yamada decides to advertise his life for sale in the newspaper classified section, and gets thrown into a series of increasingly outlandish requests from his patrons. While Mishima is most well-known for his dark, staggering works of literary fiction about tortured sexuality, obsession and beauty, like “Confessions of a Mask” and “The Temple of the Golden Pavilion,” Mishima in fact made his living with popular fiction. He wrote pulp novels like “Life For Sale” to warm up, and then turned to more serious literary fiction a few hours into his writing.

“Mishima has continued to have a readership in Japan, precisely because not all of his works are difficult to read and people can enjoy them,” Dodd says. “Mishima has an extremely perceptive understanding of the world. He really understands isolation, loneliness, and wants to get to the heart of things.”

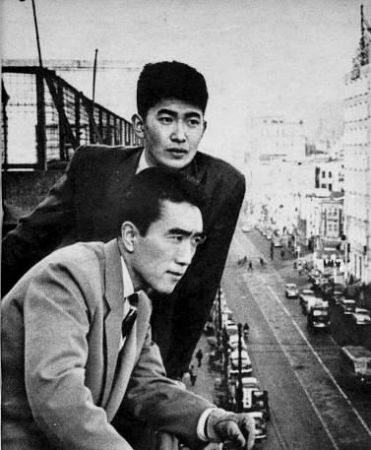

Another previously untranslated novella that came out last year, “Star,” grapples with fame and loneliness. Centering on Rikio Mizuno, a young actor in the heyday of the Japanese film industry in the early 1960s, the novel explores Mizuno’s disgust with his empty life, sapped of meaning by his unthinking fans. “Star” is another work that balances humor against Mishima’s classic darker themes.

“I found the prose really delectable and fun,” says Sam Bett, translator of “Star.” “The book has a great sense of humor. Mishima really does have a knack for putting a sentence together in a balanced way, like a spinning mobile — it has all of these different parts that are counterbalanced against each other.”

While Mishima had a complicated relationship with his sexuality, writing explicitly gay stories while often treating homosexuality with contempt, modes of queerness in his fiction continue to give his works enduring value. “There are modes of queerness in ‘Star’ that fit into the larger discussion of how his work explores gender relationships and sexuality,” Bett says.

With the resurgence of right-wing nationalism in the U.S., UK and around the world, Mishima’s problematic politics cannot be ignored. Michael Bourdaghs, a professor of Japanese literature at the University of Chicago researching Mishima, said that his goal with his suicide was to produce a spectacle for its own sake. “The point is the disturbance that you can stir up by speaking [outrageous things] aloud,” Bourdaghs comments. “I think Mishima would have understood Donald Trump well.”

Bourdaghs also points out that Mishima’s radicalism was more of a product of the Cold War-era revolutionary political struggles than Japanese pre-war fascism. “Mishima and his peers were very aware of what was going on in places like Vietnam, Algeria and other decolonizing nations, as well as in American inner cities and European campuses.” Mishima famously engaged with the student protests at the University of Tokyo, part of an inclusive ‘new left’ movement that opposed against American imperialism, Russian Stalinism and Japanese monopoly capitalism.

Mishima’s translators have struggled to get beyond the mythology perpetuated by the dramatic circumstances of his death. “It upsets me when a 20-year old reads Mishima and says, wow, that’s fabulous, he was prepared to die for beauty,” says Dodd. “It’s an egotistical reading. When we read Mishima, we have to avoid getting trapped in his web.”

“To put the matter in a crude way, Mishima used Tate no Kai as a means of killing himself,” adds Mishima translator and biographer Hiroaki Sato.

“I think we do need to get away from reading everything he wrote through the lens of November 25, 1970,” Bourdaghs says.

While scholars and critics will continue to scrutinize Mishima’s life, his varied career produced a book for everyone, no matter their taste. It’s valuable that Western audiences are now able to experience a broader scope of his writing.

“I compare him with Murakami Haruki,” says Dodd. “While Murakami is an extremely important writer whose works have touched the hearts of millions, I find his works to be repetitive. Mishima always surprises.”

Find Yukio Mishima’s translated works on Amazon

Follow us on Instagram at

@metropolistokyo