May 12, 2022

Anime and the Adverse Effects of Growth

Milking the proverbial cash cow dry

By Chris Cimi

The popularity of anime is growing faster than ever, especially internationally. Netflix reports that over 120 million households worldwide watched at least one Japanese animation title last year, just on their platform alone. With roughly another 120 million Crunchyroll (anime streaming service) accounts in existence, and new “Demon Slayer” episodes pulling in 19% viewership across Japan, we can assume that hundreds of millions of people have some Japanese cartoons mixed into their media diet.

Anime is now mainstream, or so we think. At the time of writing, Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba – The Movie: Mugen Train and the half-billion USD it accumulated, sits as the highest-grossing anime and Japanese film ever made, in addition to being the most successful film worldwide in 2020. Economically, the film saved anime from a worse fate, which brings us to our real issue. ‘Anime as an economy’ is embracing the same dire lack of creativity that has plagued Hollywood for over a decade, rehashing the same formulas for guaranteed profit.

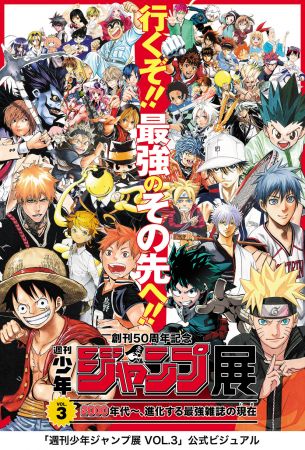

Broadly speaking, we can boil most anime down to one of two vague categories: ‘anime for the masses’ and ‘anime for anime people’—otaku, if you like. The former includes productions like Ghibli Films, Doraemon-Esque kids’ staples, and those cultivated from the ever culturally-dominating Weekly Shonen Jump. Historic juggernauts like “Dragon Ball” and “One Piece,” to today’s favorites “Demon Slayer” and “Jujutsu Kaisen,” all originated from this magazine stockpiled next to konbini cashiers every week.

Occasionally, other Shonen Magazine-derived series like “Attack on Titan” and “Tokyo Revengers” obtain real popularity—but most anime embraced by society at large hail from Shonen Jump, with its repetitive but profitable battle story formula. It is a huge equivalent to the Disney-Marvel paradigm, less because it’s comic-related and more the way it generates threads together and sells its many IPs. We might not have a ‘Jump Cinematic Universe’ just yet, but spiritually it’s always been one—having grown a worldwide fanbase that’s hundreds of millions deep for decades.

Before, kids around the world would be introduced to staples like “Pokémon” or “Naruto” and either leave anime behind as they got older or branch out to ‘anime for anime people’ shows. Now, even the most ardent of anime lovers are more vocal about Shonen Jump shows than anything made for ‘real anime fans.’ It mirrors the shambling world of cinephilia, filled with so-called movie buffs chastising Martin Scorsese for ‘not getting’ superhero films. The difference here, though, is: who could blame anime fans?

Percentage-wise, most anime are dull affairs made to sell figures of girls, models of robots, and other merchandise now likely in a landfill—but the creators used to be allowed to try. From the early 70s through the mid-2000s, creators and producers threw any and everything at the wall, seeing what would stick. Galactic trains journeying through the stars; traumatized teens who transformed into animals when you hugged them; a guy in a big red trench coat called The Human Typhoon running around Mars. Money mattered, but animators strived to grow something new, cool and moving.

Looking at the winter 2022 anime line-up, over 20% of new anime can firmly be called isekai; the formulaic, wish-fulfillment sub-genre that sees hapless regular earthlings sent off to RPG-inspired alternate worlds and net a bunch of girls. Another 30% in the line-up are sequels, and the rest are a dozen other shows about high school girls.

Admittedly, like the moé boom before isekai, and the borderline softcore material before that, ‘anime for anime people’ has always produced a lot of crap; every so-called ‘masterpiece’ is released alongside a heap of dung no one has thought about since it finished airing. Works of Japanese animation that strive for some greater artistic or narrative expression, as opposed to just profit, are fewer and further between than ever before.

Just as Hollywood has figured out that milquetoast sequels and spin-offs to existing franchises net the biggest profits, the once creatively fertile ground of anime has been largely repurposed to cultivate exactly two strands of Japanese animation; teen boys with superpowers fighting each other, or teen boys in generic Tolkienesque landscapes romancing priestesses and elves. This doesn’t mean to imply it’s all bad, but go back to something like “Cowboy Bebop,” and you’ll see there used to be more artistry to it all.